If this column has a principle for selection, it is that books should be bendy and small enough to read on public transport; ideally, to fit in a pocket. Well, this is a paperback, but I doubt it would fit in even a clown’s pocket. As it is about public transport, though, here it is.

Great Railway Maps of the World is a mesmerising and thought-provoking book. Just because it is light on the text and heavy with the images does not mean it isn’t conducive to enlightening reverie. It delivers 130 or so pages of colour railway maps, from the earliest days of steam travel to the modern age. Inevitably, this is mostly a story of (possibly reversible) decline. We may be familiar with the loss of thousands of branch lines in Great Britain thanks to Dr Richard Beeching, and wince when we look at the pre- and post-Beeching network maps; but even more striking is the juxtaposition of Argentina’s railways in 1989 with those in 2001. The former picture looks like a thumb stuck into a butterfly net, the latter like a thumb with a string dangling off it. “Following closures and privatisations,” says the caption, “this was the sorry state of passenger rail services in Argentina in 2001.” You notice the p-word there? It’s never, when it comes to railways, good news: except at the very beginning, when that was all there was, and the car hadn’t been invented. (The chapter dealing with the decline of the railways is perhaps to be avoided by those of a delicate constitution.)

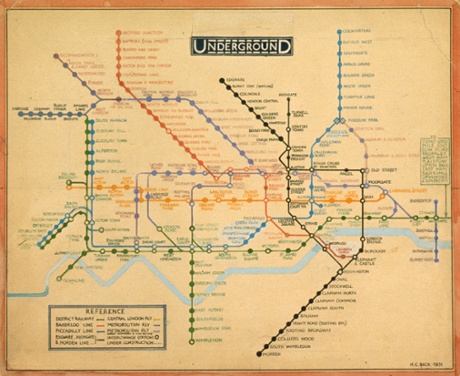

But, on the whole, this is a beautiful and inspiring collection. You don’t have to be nutty about railways to revel in it, you simply have to appreciate good design, in which the demands of conveying information and stimulating desire contend. Anyone who has ever nodded in appreciation at Harry Beck’s tube map – reproduced here, but overlaid with all the overground rail services available in the 1930s as well – will marvel at, for instance, Kim Ji-hwan’s 2009 Tokyo tube map, which still looks as though it has come from the future. I’m not sure I’d like to use it to find my way around, yet it is a thing of beauty.

Generally, because the history of railways began before abstraction in art, the maps follow the routes in geographical accuracy; the ingenuity of the designers lies in how to turn that into fancy. Ovenden notes that as the railways grew designers were encouraged to give their imaginations wings. Or paws: there’s the pointer with its tail stretching over Duluth and its snout in Olympia advertising the Northern Pacific Railway Company; or the alligator with its tail in Jacksonville and its left foreleg reaching to Chicago. These designs turned railway routes and their destinations, subliminally, into new constellations.

Then there are the pleasures of nostalgia, real or imaginary: you can delight in the art of, say, the early 20th century, designed to inspire a weary population with holiday destinations. On one page alone there are posters, from between 1907 and 1911, claiming “the most interesting route to Scotland” (with a Black Grouse holding a ribbon in its beak saying “the cock o’ the North”); a rather sinister clown pointing to a map of the north-east coast around Whitby and Scarborough announcing “England’s ‘Playground’”; and a lion proudly looking over a stylised, foreshortened route from Mombasa to Port Florence (with only one stop in between indicated: Nairobi) with the legend “step by step through nature’s ‘zoo’”. Those inverted commas around “playground” and “zoo” prompt a raised eyebrow (isn’t natures’s “zoo”, um, nature?), as does, for different reasons, the phrase “Sunny South Wales”. But you want to believe in such things, and the green-washed poster for the Norfolk Broads, whose train line underneath has a section labelled “Poppyland”, is like a dream of the Broads themselves. We travel, here, not only in space, and time, but into and out of ourselves.

• To order Great Railway Maps of the World for £11.99 (RRP £14.99) go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846.