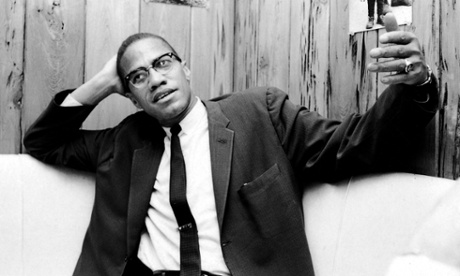

The Portable Malcolm X Reader (edited by Manning Marable and Garrett Felber)

As the 50th anniversary of Malcolm X’s assassination approaches (21 February), this collection of essays, FBI files, newspaper articles and speeches offers a chance to see the controversial civil rights leader and black nationalism advocate in a different light. Marable and Felber dig deep into his past with police reports that detail the time his family home was firebombed in Michigan in 1929 and also provide the Muslim leader’s own rap sheet; ranging from stealing a fur coat to carrying an illegal firearm.

On their own, the details would add up to little more than curios of a complex and often overlooked figure from America’s recent past, but coupled with the various newspaper articles that chart his rise through the ranks of the Nation of Islam (and into an American media personality) and essays by the likes of James Baldwin, the editors begin to paint a picture of a man who was always evolving, constantly learning and forever capable of moulding and revising his own philosophy. There’s insight into how he was interpreted after his death too, with Baldwin writing about the nixed biopic planned in the late 60s (“It was simply a subject Hollywood could not manage”) and a letter from publishers to Alex Haley apologising for not being able to publish his now famous autobiography. LB

The Price of the Ticket (by James Baldwin)

It’s rather extraordinary, if slightly grim and unsettling, how relevant this seminal collection of James Baldwin’s essays are today. First published in 1985, the book includes 50 of Baldwin’s best works that span the course of several decades. It serves as an intellectual primer on race in America, but it is also a tour de force of magnificent writing. His commentary on race, black identity, white delusion and the state of humanity was not only fearless, but achingly poignant and exacting. The essay that I always return to is A Talk to Teachers, originally published in The Saturday Review in December 1963. Baldwin plainly lays out the purpose of the American education system (“A process that occurs within a social framework and is designed to perpetuate the aims of the society”) and then proceeds to lower the boom on the paradox in how it affects Black children in America (“… any Negro who is born in this country and undergoes the American educational system runs the risk of becoming schizophrenic”). Baldwin, never one to let a society sanctioned process dictate his self-worth, flips the script and turns the essay into a beautifully righteous statement on individualism and self-invention. RC

March: Book Two (by John Lewis, Andrew Aydin and Nate Powell)

The Selma to Montgomery marches are the historical event that this year’s Black History Month is focusing on. Ava DuVernay’s film Selma has been the focal point for most of the attention but this graphic novel (as told by civil rights activist congressman John Lewis and co-writer Andrew Aydin and illustrated by Nate Powell) helps paint a picture of the events leading up to the historic marches. It’s part of a trilogy released by Top Shelf that – much like the oral history of the civil rights movement My Soul Rested by Howell Raines – charts the rise and often violent reaction to non-violent protests.

Activists are beaten as they try to buy a cinema ticket in the segregated south, a restaurant owner lets off a potentially deadly fumigation capsule after locking protesters in, mobs attack those taking part in civil disobedience on what seems like every other page. Unlike Selma, Martin Luther King isn’t in every scene, and in fact more attention is given to peripheral figures who Lewis remembers such as A Philip Randolph and Malcolm X. Martin Luther King does appear though and when he does Lewis remembers how at the time everyone, from the bigoted Alabama police commissioner Bull Connor to liberal white leaders, criticised the demonstrations and action. The most poignant passage is when he recalls the rewriting and infighting over the content of Lewis’s speech during the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. LB

Time On Two Crosses: The Collected Writings of Bayard Rustin (edited by Devon W Carbado and Donald Weise)

Bayard Rustin was one of the great, if unfortunately little-known, American political thinkers of the 20th century. The openly gay Rustin was a close advisor to Martin Luther King and a co-founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Born a Quaker, he went to prison as a pacifist conscientious objector during the second world war and was convicted of homosexual acts in 1953, before being the chief organizer of the March on Washington in 1963. Time on Two Crosses, just revised and reissued with a new forward by Barack Obama (who posthumously awarded Rustin the President Medal of Freedom in 2013) and afterward by gay former congressman Barney Frank, is a stunning collection of Rustin’s writings. It includes his seminal 1986 speeches The New Niggers are Gays and From Montgomery to Stonewall, along with meditations on MLK, Muhammad Ali, Malcolm X, Louis Farrakhan and Joseph Beam. ST

Death of a King: The Real Story of Dr Martin Luther King Jr’s Final Year (by Tavis Smiley)

In this painstaking account of the last year of Dr King’s life, journalist and talkshow host Tavis Smiley seeks to remind us of the humanity, values, and challenges that characterised the civil rights leader, but that have been largely “sanitised and oversimplified” by history. Starting with 4 April 1967, Smiley shows how King’s attempts to unite the civil rights and anti-war movements alienated him from President Lyndon Johnson, members of the NAACP, and the black middle class, groups that had once been his largest supporters. The book also features the insight of The Rev Jesse Jackson, Harry Belafonte, former Atlanta mayor Andrew Young, and others close to Dr King, who provide a sense of his inner turmoil. As with the film Selma, Death of a King brings to life the complex individual who came to represent the hopes of an entire people. KM

Who We Be: The Colorization of America (by Jeff Chang)

As America transitions towards becoming a majority non white society in 2043, Jeff Chang’s beautiful magnum opus is a must read in order to understand the role of race in who we are and where we’re going. Chang – who sometimes writes for the Guardian – paints a racial portrait of a nation which exists beyond a black/white binary as he critiques “whiteness,” “multiculturalism” and “identity”. Riffing on Shepard Fairey’s “HOPE”, Arcade Fire’s lyrics, and the artwork of Hank Willis Thomas and Glenn Ligon, Who We Be calls on America to stop pretending it is post-racial when what is so desperately needs to be is post-racist. Visually driven for the internet age, Who We Be has the intellectual depth of an academic book, while mercifully lacking that form’s oft poor writing and out-of-touch feel. ST

The Misadventures of Awkward Black Girl (by Issa Rae)

There are so many things right with this book, I don’t even know where to begin. I’m sure many reviewers will talk about it in the context of Issa Rae’s charismatic, offbeat sense of humour that has earned her an enormous following through her same-titled web series, The Misadventures of Awkward Black Girl, and they would be right. She is funny as hell, but what I find so striking about Rae and her work as a writer, director and actor, is the stone-cold honesty of her self-representation and individuality. Her integrity is in the tenor of her voice on every page of the entire book. It’s in the happily strange descriptions of her life growing up in various locations, including Senegal, Maryland and Los Angeles, and the pitch-perfect personal disclosures that bear not a whiff of self-pity. In an essay about her relationship with food and her fluctuating weight, she notes: “I’ve resolved many times to force myself to get a grip, exercise, and eat right. … As of late, I can last for six days maximum before I wild the fuck out.” Rae is black, and she is awkward, and she is a girl, but she is also a beacon of success through self-awareness in an era when Kim Kardashian’s ass breaking the internet is the bar. RC

Disgruntled (by Asali Solomon)

Asali Solomon’s debut novel, Disgruntled, centres around Kenya, an eight-year-old girl growing up during the 80s in west Philadelphia. In this nuanced, funny and gorgeously written coming of age tale, Solomon crafts an intimate narrative that explores a broad scope of Black life – from Kenya’s Afrocentric black-nationalist parents, who institute Kwanzaa over Christmas, and are members of The Seven Days (a nod to Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon), to being the only black student at an all-white private school, double dutch, activism, incarceration and domestic abuse.

What makes the novel a standout is Kenya’s relationship to, and perhaps not with, her father, Johnbrown Curtis, a haunted race man, both buoyed and burdened by the cause. Or, as Kenya’s mother Sheila tells her daughter: “He’s so stuck on this business about being black … like he’s the first person to have that problem.” Sheila is the breadwinner of the family, while Johnbrown works obsessively on a secret project called the Key that may or may not change the quality for black people, but is nevertheless a high-brow intellectual work-in-progress to be revered. Moreover, for Kenya’s purposes, it might ultimately provide insight or resolution to “the shame of being alive … a phrase Kenya would hear in her father’s voice,” and grows deep in Kenya’s consciousness and which she struggles to understand as she comes into young adulthood. RC

Jam on the Vine (by LaShonda Katrice Barnett)

Editor and music scholar LaShonda Katrice Barnett goes big for her first novel, Jam on the Vine (out 10 February from Grove Press). It’s the multi-generational, many-voiced story of the vibrant, aspiring journalist Ivoe Williams, and her family, living, but struggling in a poor and racially segregated town early 20th century Texas. When her family moves to Kansas City, Ivoe is finally able to jumpstart her career as a journalist, co-founding the city’s first black female-run newspaper Jam! On the Vine. But in the midst of bitter violence toward blacks, her challenges surpass writing and publication to the moral obligation she faces to acknowledge the unjust. Barnett brings the musicality at the center of her critical work to the language and style of this, her big, bold bildungsroman of a debut. KM

The Boy in the Black Suit (by Jason Reynolds)

Poet and young adult novelist Jason Reynolds made a critical splash when his first book, When I Was the Greatest, was published by Simon & Schuster last year. Now, after being heralded as the heir to the black YA throne by the late Walter Dean Myers himself, he’s back with a new book, The Boy in the Black Suit. Matt Miller is a 17-year-old boy dealing with the sudden loss of his mother. On top of that, he’s got a dad who can’t cope (but can drink), a job at a funeral home, plus, his senior year of high school to finish – challenges that seem insurmountable until he meets Lovey, a girl who’s been through much worse yet seems to be in better shape. If Reynolds’ recent Coretta Scott King New Talent Author Award is any indication, the kingdom of black young adult literature is safe. KM