According to the Oxford English dictionary, the word “normal” is defined as “Conforming to a standard; usual, typical, or expected”. On paper, this sounds majorly dull, and yet as a teenager I spent a frightening amount of time obsessing over whether I was “normal” or not. Unbeknownst to me at the time, most of my friends were doing exactly the same, all of us silently fretting over the circumference of our thighs or less than brilliant exam results or imperfect complexions, caught in a never-ending spiral of unhealthy comparison.

I wasn’t a “typical” teenager. I listed model villages, Hollywood musicals and my pet rabbit, Juniper, as my favourite things. Meanwhile I was utterly convinced I‘d been born in the wrong era, and didn’t kiss a boy until I was 18 years old. My diaries from this period reveal I embraced my oddities but at the same time longed to experience the normal rites of passage I read about in the American teen novels I devoured. The pressure to be perfect didn’t come from Heat magazine or photo-shopped selfies (this was in the days before the internet) but from stories of gorgeous teenage girls getting straight As by day and going on hot dates by night.

Last year I spent an afternoon hanging out with a group of teenage boys and girls. When I asked them what they worried about most, they all agreed “image” and “self-esteem”. These kids were bright, witty and articulate but also clearly struggling to balance the desire to fit in whilst maintaining their individuality. The main source of peer pressure may have moved online, but the preoccupation with aspiring to “normality” still looms large.

I began working as an administrator at the Gender Identity Development Service (an NHS service for under-eighteens struggling with their gender identity) in 2010. The young people who visited the service were grappling with the concept of “what is normal?” on a whole other level to what I’d experienced as a teenager, their confusion and distress over their gender identity heightened by society’s expectations of how teenage boys and girls should look, sound and behave.

Having always felt comfortable as female, I was surprised at how much I related to the patient stories I heard. Their sense of not fitting the mould was 10 times more extreme than mine, but ultimately feeling different and the anxiety this can inspire is something almost all of us can relate to. Several young people admitted the most upsetting aspect of what they were going through was the lack of acceptance. Although some had the support of family and friends, others were dealing with extreme hostility and isolation as those around them struggled (or refused) to adjust to a life a little less “normal”.

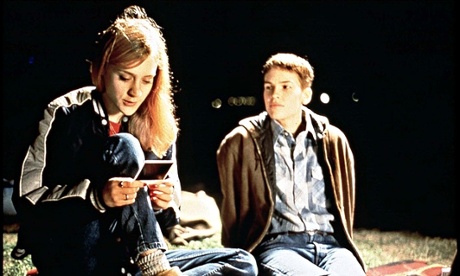

My book The Art of Being Normal is about two teenagers, each with a secret, each struggling to fit in. David longs to be a girl but is too afraid to tell his parents how he feels. Leo is the new boy at school with the bad reputation. Separately and together they explore “what is normal?” through their experiences over one term at school, the two of them constantly torn between wanting to be “normal” (or their imagined version of it) and embracing who they naturally are, all whilst negotiating puberty, falling in love, friendships, family and bullies.

I suspect the pressure to fit in never really leaves us. At 34 years old, although I can mostly claim not to give a monkey’s about what people think of me, there’s still that tiny corner of my brain that can’t help but care.

It’s no coincidence that the majority of people reading (and relating to) young adult fiction in the UK right now are over 18. Our teenage existence is packed full of hugely vivid experiences and “firsts”, good and bad that shape our lives in ways that are sometimes not immediately clear. It’s this enduring power that makes the fictional recreations of teenage experiences so appealing to readers, often long after their eighteenth birthdays.

The sorts of books I would have killed to read as a teenager now line the shelves of our libraries and bookshops. Instead of perfect California girls with white teeth and shiny hair and their hunky male counterparts, the literary heroes and heroines of this generation are geeks and goths and misfits. They have flaws and quirks. They make mistakes and have regrets. They’re diverse. They’re human. As the media continues to bombard us with a distorted, airbrushed representation of what is “normal”, it’s a joy and relief that fiction aimed at teenagers is bucking the trend, constantly striving to examine and reflect the imperfect realities of life for young people today.

Lisa Williamson’s debut YA novel The Art Of Being Normal is available at the Guardian bookshop.

Do you think teen and YA books are diverse enough, or is there still some way to go? Join the discussion by emailing childrens.books@theguardian.com or on Twitter @GdnChildrensBks. Also see our blog What are the best LGBT books for children and teenagers?