In 1963, Terence Ranger, who has died aged 85, was deported from Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). He had earned the enmity of the country’s minority government for his engagement with a burgeoning African nationalist movement and for doing so from within the respectable halls of what was then called the University College of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, the only university in Salisbury (now Harare).

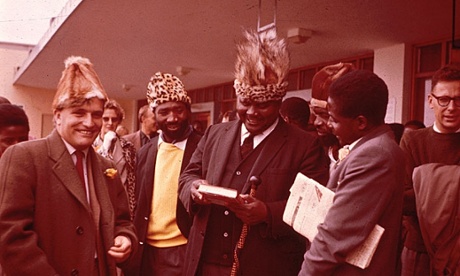

With his wife, Shelagh, and a key group of colleagues, he campaigned against the colour bar, edited the groundbreaking journal Dissent and formed the Southern Rhodesia Legal Aid and Welfare Fund to defend the many hundreds of nationalists kept in preventive detention. He was among a handful of white people who held office in the African nationalist movement, earning the vilification of white settlers. He formed fast friendships among an extraordinary multiracial group of fellow liberals, radical Christians and nationalists that would endure for a lifetime.

Before moving to Rhodesia in 1957, Terry showed few signs of such radicalism – or of his future career as one of Africa’s most influential historians. Born in South Norwood, south-east London, to Leslie, who ran a chromium plating company, and his wife Anna (nee Bradford), Terry attended Highgate School, north London. He was not markedly political as a scholar at Oxford, where he completed a BA in history at Queen’s College and a doctorate at St Antony’s. His thesis focused on 17th-century Ireland.

It was on the basis of an article in the Times by Basil Fletcher, the vice-principal of the University College of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, that Terry, then teaching at the Britannia Royal Naval College, Devon, decided to apply for a lectureship in the history department. He went as an idealist and egalitarian, attracted to the idea of a multiracial society, but the place made him into something much more radical. It also threw him into the field of African history. Before his expulsion, the Rhodesian authorities had “restricted” Terry to within a three-mile radius of his home, a narrow space that luckily encompassed the national archives and he took full advantage by burrowing deeply into the records.

When Terry was deported, he took a large collection of notes with him to his new history post in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and used it to write two groundbreaking monographs, Revolt in Southern Rhodesia (1967) and The African Voice in Southern Rhodesia (1970). These histories of resistance provided African nationalism with a heroic past and established a style of writing that was accessible, alive with direct quotation, and driven by a compelling narrative. During the same period, Terry wrote an innovative book on popular culture, Dance and Society in East Africa (1975).

He did all this in the midst of a newly independent country and in the heady company of both a great many exiled African nationalists and an extraordinary new generation of historians who made up his department, among them John Lonsdale, John Iliffe and John McCracken, all of whom went on to stellar careers in British universities, the first two at Cambridge and the latter at Stirling. Together, they would break from the comfortable assumptions of colonial historiography and set the telling of Africa’s story on a new path.

Following 12 tumultuous but productive years in African universities, in 1969 Terry went to the US to work at the University of California, Los Angeles, where his research on African religion bloomed. He returned to Britain in 1974 to take up a professorship at Manchester University, where he focused on Zimbabwe in anticipation of independence in 1980. With the change of regime he was allowed back into the country, and did the research for Peasant Consciousness and Guerrilla War (1985), a comparative account of the ways in which ideas were formed among rural people. In 1987, he was appointed to the Rhodes chair of race relations at Oxford, where he established a lively lecture series and a home for Africanist study that thrives to this day. In the 1990s he undertook two key research projects on the history of the Matabeleland region, Voices from the Rocks (1999) and Violence and Memory (2000), as well as Are We Not Also Men (1995), a biography of the Zimbabwean Samkange dynasty, drawing on their extraordinary collection of personal papers.

After his retirement in 1997 Terry returned to the campus where he first started, now the University of Zimbabwe. He encouraged a new generation of Zimbabwean historians amid a period of intensifying upheaval very different from the early 60s but involving some of the same nationalist figures, Robert Mugabe paramount among them, now as repressive rulers rather than freedom fighters.

On his return to Oxford in 2001 he published a sparkling foray into Bulawayo’s urban cultural history, Bulawayo Burning (2010), published influential articles on Zimbabwe’s continuing crisis and engaged passionately iin the politics of asylum in Britain on behalf of Zimbabwean refugees, a fitting if awful echo of his work on behalf of political detainees in 60s Rhodesia. In 2013 he published his memoir, appropriately titled Writing Revolt.

Throughout his career, Terry brought African history into mainstream institutions and debates: he was the first Africanist fellow of the British Academy and the first historian of Africa to sit on the board of the historical journal Past and Present; he co-edited major collections, the most influential being The Invention of Tradition (1983) with Eric Hobsbawm. His contribution to Africanist institution-building was also important. He was co-founder of the Britain-Zimbabwe Society, president of the African Studies Association of the UK, and a key figure in innumerable journals and societies.

Terry was never a grand theorist, “preferring the role of the light-footed guerrilla to that of the philosopher king”, as McCracken aptly put it. While he made significant contributions to comparative and theoretical debates over resistance, religion, and social identity, he was at his best exploring the complexity of ordinary people’s ideas.

He is survived by Shelagh (nee Campbell Clarke), whom he married in 1953, their daughters, Frances and Malaika, and nine grandchildren.

• Terence Osborn Ranger, historian, born 29 November 1929; died 3 January 2015