Three months before the 1992 election, with Labour and the Conservatives – as now – sweatily close in the opinion polls and a grappling pre-campaign under way, one of the admen Labour were using phoned his Tory counterpart. “Congratulations!” said the Labour adman. “What for?” said the Tory adman. “You’ve won the election,” said the Labour adman. “You’ve hit us on tax and we haven’t responded properly … I’d like to take you for a very expensive meal to congratulate you.” Soon afterwards, the two men – the protagonists in this swaggering book almost always are – had dinner in Soho. Soon after that, the Conservatives defied widespread forecasts of a Labour victory or hung parliament by winning outright, with the largest vote ever secured at a British general election.

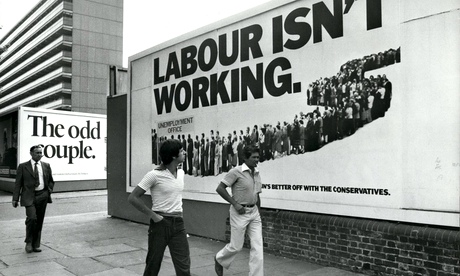

Mad Men and Bad Men is a history heavily dependent on good anecdotes. It divides the half century since admen first took on the challenging job of selling British politicians and parties – and the easier one of rubbishing rival political products – into bite-sized chapters, like a tasting menu, which the general reader can quickly work through without spoiling their appetite. Famous admen such as Tim Bell and Charles and Maurice Saatchi strut and slither through the narrative, sometimes even more cunning and shamelessly pragmatic than the politicians. A few years before the Saatchis helped Margaret Thatcher into power with their celebrated late-70s poster assault about joblessness under the Callaghan government, “Labour Isn’t Working”, Delaney notes tellingly that their ultra-ambitious agency produced some posters for Labour. The theme of this long-forgotten campaign? The difficulty of reducing unemployment.

Delaney has written a previous, less politically focused book about modern British advertising, Get Smashed: The Story of the Men Who Made the Adverts that Changed Our Lives (2007). He comes from a family of admen: his father, Barry, and uncles Greg and Tim are all industry names. Mad Men and Bad Men describes the incestuous, sometimes disingenuous world of London advertising with authority and clarity.

The harder task this slim book faces is to bring something new to the story of British politics. Anyone reasonably well-versed in it will already know about the legendary handful of posters and party political broadcasts with a claim to have influenced the results of general elections – not least because Bell et al have profitably reminded us about them ever since. Nor is the fact that the Conservatives usually have the best and most talked-about advertising – something Delaney makes much of – necessarily of great significance any longer. For all their expensive and exhaustively choreographed poster bombardments, the Tories haven’t actually won a general election since their 1992 surprise triumph.

As early as the 50s, the party hired admen to apply market-research methods to the identification and attraction of key voters. At the 1959 election, a Conservative government which had already been in office eight years, usually long enough to disenchant the electorate, almost doubled its Commons majority under the slyly sunny-but-barbed slogan, “Life’s Better with the Conservatives. Don’t Let Labour Ruin It.” Expect to be browbeaten by its descendants over the coming weeks.

Labour began taking an interest in political marketing soon afterwards. During his zestier early governments, Harold Wilson successfully used a trio of advertising, PR and media-management professionals known as the “Three Wise Men”. Twenty years later, in the mid-80s, during another period of Labour preoccupation with matters presentational, the newly hired spin doctor Peter Mandelson was introduced to one of them, Peter Lovell-Davis. “I was invited to his house in Highgate,” Mandelson tells Delaney in one of several revelatory interviews here. “He had this huge archive of [Labour] marketing memorabilia from the 60s and 70s … It became the basis of the changes I eventually made to the party image.”

Delaney’s material about early political advertising is fresh and spiced with surprises – such as the fact that his uncle Tim worked on a forgotten, state-of-the-art anti-Tory campaign in the late 70s for supposedly fusty old Callaghan. The Thatcher-era chapters that dominate the middle of the book are lively but less intriguing. Her chocolatey-voiced favourite, Bell, makes a good interviewee, as always: explaining that the “key trick” to persuading the self-important Tory hierarchy of a particular advertising strategy “was to give them a little nugget of information to take away”, such as “the reason we are using that particular font … is because it is the oldest font in existence”.

But there are no interviews with the Saatchis. And there is no new information about, or interpretation of, the “Labour Isn’t Working” campaign, despite Delaney calling it “the poster that changed everything”. Instead the book breezes along, like an adman cruising down Charlotte Street in a new convertible, or a modern TV documentary skilfully steering clear of anything too complicated or counter-intuitive, with Delaney’s bright, matey prose linking the interviews like a voiceover: “There was still no word from Maurice Saatchi. What was his problem? Well, whatever, I went back for a chat with the creative overlord of his agency, Jeremy Sinclair … ”

In Delaney’s entertaining but rather conventional account, the admen – usually taken at their own estimation, without much cross-checking – dazzle and brag, guzzle champagne and cocaine, and come up with brilliantly clarifying ideas. Meanwhile the politicians are generally cautious and verbose and bureaucratic. He quotes Sinclair, who has worked for the Tories for decades: “Making ads forces you to sieve your thoughts … to get the essence of your argument. All the waffle and detail that a politician can get away in a speech isn’t allowed … We helped politicians understand how to speak to people in a way that they could hear.”

More originally, the book shows that this simplifying – many would say shrinking – of politics has not been a relentless process: the influence of admen over the main parties has ebbed and flowed, depending on their leaders’ attitudes to presentation and communication; on whether the parties can afford the admen; and whether the polls are close enough to make ads seem worthwhile. During the 1983 election campaign the Tory chairman, Cecil Parkinson, became so confident of victory, with his party consistently almost 20% ahead of Labour, that he abruptly cancelled the final week of Conservative advertisements, to the consternation of the admen. “All of those newspaper spreads would have won [Saatchi & Saatchi] all sorts of plaudits,” he tells Delaney. “But [they] would have cost us millions and … we got a majority of 146 without [them].”

Yet for more anxious or vulnerable parties, ads have an unspoken value beyond the electoral. They boost internal morale: during the 2001 election, Delaney deliciously records, Tony Blair and Alastair Campbell “would take diversions during car journeys in order to seek out Labour posters”. Ads can also make voters and the media think a party is slicker, more sure of itself, and wealthier than it actually is.

Whether these symbolic functions will survive much longer in the digital age, with online poster parodists ready to pounce, is something the book considers too briefly – like the present state of political advertising in general. Lynton Crosby and the other shadowy current masters of electoral communication were presumably too busy to talk. Nor does Delaney ever fully acknowledge that one reason ads resonate with voters, beside the adman’s caffeinated alchemy of catchphrase and image, may be that the boring old politicians and traditional media have created a context for them first. “Labour Isn’t Working” hit home partly because Thatcher and her newspaper allies had already convinced many voters that Callaghan’s Britain was grinding to a halt. Without such deep swells in public opinion, as Labour and the Tories may discover this May, political ads are often just froth.

• Andy Beckett’s book about how Britain changed in the early 80s, Promised You a Miracle, will be published by Penguin in September. To order Mad Men & Bad Men for £11.99 go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846.