We have barely stumbled into 2015 and already some commentators are calling time on the ebook. The analysis was provoked by Waterstones’ managing director, James Daunt, who told journalists sales of Kindle devices “disappeared” over Christmas 2014, leading to reports that the digital market had peaked and was in retreat.

But the facts tell a slightly more nuanced story: this is more a tale of the unexpected than a chronicle of a death foretold. .

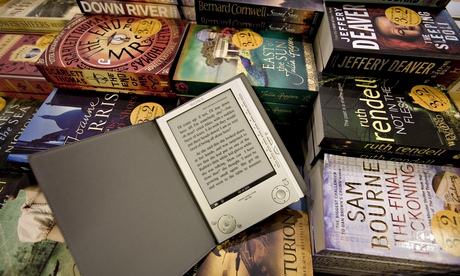

The ebook arrived roughly in 2009, and while it did not kill the print book, sales of devices and ebooks did grow extraordinarily quickly. In the UK, between 2010 and 2013 the market went from practically zero to £300m, partly because of titles including Fifty Shades of Grey and Bared to You. These – we later understood – were popular purchases for those who chose to read behind the relative anonymity of a screen. Around the middle of 2013, we saw the pace of this shift slacken as the number of heavy-reading early adopters dropped off and readers caught up with the books they had energetically loaded on to their new devices.

But this is not the same as a market in peril. The rise of these electronic devices built only for reading has been a boon to the books sector. The transition to digital reading brought with it a new kind of publishing that was distinctly more experimental, energetic and (nakedly) commercial than that which preceded it. Just this week the publisher Little, Brown began publishing ebook shorts based on the hugely successful Broadchurch TV series that are made available to download in the hours after each show.

Outside of traditional publishing, digital reading has allowed authors to publish directly to marketplaces run by Amazon, Nook and Kobo. We have also seen the rise of fan-fiction sites (one of which helped create Fifty Shades) and writer development sites such as Wattpad and Movellas.

There is a vibrancy and quickness around publishing that can be directly linked to the arrival of the ebook. It has helped revive the print book market, with titles such as The Miniaturist and H is for Hawk published as beautifully rendered physical editions to be held, read and kept. The better publishers understand the boundaries of these different channels, the better they have become at delivering content to them.

Christmas 2014 saw high-street booksellers sell more print books than the year before, but those that stocked e-readers sold far fewer of them than in 2013. Daunt’s reasoning was that Waterstones’ customers who would like an e-reader had already bought one. Fair point. But more saliently, who gives a single-use e-reader for Christmas when rival tablets – such Tesco’s Hudl, Amazon’s Kindle Fire – are now so much cheaper?

This shift from e-reader devices to tablets has been talked about for some time but it tells us little about sales of actual ebooks. Technology becomes obsolete almost as quickly as it is adopted these days – but the habits it forms last much longer.

Statistics about this market are closely guarded by Amazon, which still has an 80% share of ebook sales. But my analysis is simple. The digital book sector in the UK will be bigger in 2014 than it was in 2013 (perhaps closer to £400m than £350m) and it is likely to have grown faster than any other section of the books market (though children’s books may run it close). Add in digital audio books, book apps and digital academic textbooks, and we see a sector broadening not wilting.

The market will experience unexpected sales patterns as it matures – already we see stronger sales of digital content in the summer before the holidays, with Christmas a poor period for digital sales as customers switch their personal buying to gift purchases. Tablets bring challenges and opportunities. What better device is there for a publisher than one built only for reading? If readers truly stop buying Kindles and switch to iPads or cheaper alternatives, there will be more experimentation around content and how it is paid for, with book subscription services such as Scribd and Oyster – or those run by audio-book companies including Audible and Bardowl – coming to the fore.

When she won the Bailey’s prize for women’s fiction, Eimear McBride remarked that “to be a reader is a fearless thing”. I see a parallel in how we think about the digital book market. As a sector we are often guilty of playing print sales off against ebook sales, as if the rise in one format must always be to the detriment of the other. But this is not the case.

For years journalists have been wanting to write about the end of the printed book, now they want to spin a similar tale about ebooks. But the reader doesn’t care. They have proved to more promiscuous and more flexible in what and how they read than anyone predicted. They are still reading. The printed book never died – long live the ebook.