Joaquin Phoenix sucks on a cigarette and paces the room like a skittish fox examining nooks for potential boltholes. There aren’t any. It’s the 20th floor, the window is sealed and I’m standing in the doorway. He turns. “The Guardian! Oh fuck!” A bristly encounter with one of Hollywood’s most enigmatic leading men appears imminent. But he strides over, offers his hand and creases into a grin. He’s not in a bad mood, merely edgy.

He continues pacing, oblivious to the leather armchair, pausing to take in the view of downtown Los Angeles on a sunlit, winter afternoon. It’s a jolt to realise this is Phoenix as Phoenix. He so immerses himself in roles, and so loathes the celebrity game, cloaking himself in privacy or diversionary stunts, there is seldom a peek at the man himself.

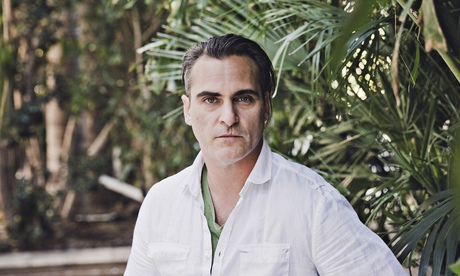

Known to be sensitive and at times temperamental, in 2010 he made the mockumentary I’m Still Here, in which he renounced acting, grew a Unabomber beard and shambled around as a mumbling, wannabe hip-hop artist. Many people were alarmed because he seemed the sort of artist who really could go over the edge. Today, however, he sports a trim beard, groomed curls and a natty blue scarf over a white shirt. With his skinny jeans he could, from a distance, be mistaken for a hipster.

He eventually surrenders to the armchair and proves affable, thoughtful and grounded as he ruminates in a slightly raspy voice on the perils of awards, the difference between good and bad acting, why he has yet to appear in a superhero film, whether he’s a muse – and why stardom begets insincerity. He would rather be at home with his dogs than in a hotel plugging his latest film, he confides. “But I’m here. And I hate the sound of my own voice saying the same shit. And I hate being insincere, which inevitably I’m going to be at some point because I can only do this for so long before I run out of genuine enthusiasm.”

There’s clearly still plenty in the tank because he says this with passion. But he’s going to be hearing his own voice a lot these next few weeks as he promotes Inherent Vice, a Paul Thomas Anderson-directed stoner romp based on Thomas Pynchon’s 2009 novel of the same name.

Phoenix plays Doc Sportello, a private detective who stumbles in a narcotic haze through LA at the fag-end of the 1960s trying to solve a byzantine case involving his ex-girlfriend, a missing billionaire, drug smugglers, tax-dodging dentists and thuggish cops. It had been mooted for Oscar glory but the Guardian’s Xan Brooks, who loved it, thinks academy voters may find it “too wild, baggy and disreputable”. And so it proved. The film has just two nominations – for adapted screenplay and costume design.

Phoenix’s performance as the zonked Columbo – with mutton-chop sideburns inspired by Neil Diamond – has won near universal praise. Following equally acclaimed turns in Spike Jonze’s Her, where he played a man in love with an operating system, and Anderson’s The Master, an Oscar-nominated depiction of a war veteran in thrall to a cult, the 40-year-old is on a roll. It feels like a comeback, as if the star who delivered Oscar-nominated performances in Gladiator and Walk the Line, has roared back after a self-imposed break.

He ponders this. “No, it doesn’t feel like a comeback. I’m just … really grateful that I’ve had these great opportunities. I’m working with these directors that I really admire.” It sounds like Hollywood guff but Phoenix really does revere directors – some directors.

Actors, he says, often get credit for supposedly going deep into roles when really what audiences are experiencing are environments created by maestros behind the camera. “Actors themselves probably perpetuate that myth. And every once in a while maybe it’s true. But if a movie works, it’s the director.”

You could expect such self-deprecation from Roger Moore, say, but Phoenix sublimely channelled Johnny Cash in Walk the Line and invested complexity into Her’s potentially ridiculous Theodore Twombly.

At the age of 40 Phoenix still bristles at the pressure to memorise lines and hit marks from his time as a child actor. He prefers an organic approach. “I just like to discover things as they go along. I try more and more to be receptive to what’s happening in the moment as opposed to creating these ideas and trying to impose them on the shoot. The best feeling is when you don’t think you’re saying the lines. You think you’ve fucked it up and you’ve just been talking. And you go, oh, did I get that wrong? And they say no, everything was there.”

Good actors bring a script to life, he says. “And that’s a real art, it’s really impressive. But I always wanted to be open to finding something that I didn’t intend or expect.” He compares it to athletes being in the zone, a trance-like state where everything goes right.

“To get to the place that’s beyond the technical side of finding your light or saying the line in a particular way and being open to your unconscious because I think sometimes it knows better than you.”

He lights up another cigarette. “Anytime I try to implement my ideas, it’s always bad,” he laughs. “It’s always fucking bad. And I feel the best stuff is kind of out of my control. I never quite feel responsible for it. And that’s the state that I want to be in when I work.”

His left leg quivers with nervous energy but discussing acting, his favourite topic, seems to calm it. The twitching resumes when conversation turns to the awards circuit. In a 2012 interview he branded it “total, utter bullshit”, a circus he wanted no part of. He rubs his chin and clears his throat. “Awards can do amazing things for an actor’s career,” he says. “The Oscars have completely changed my career for the better.” He hesitates, frowns. Sincerity and circumspection, one senses, are jousting in Phoenixdom. Sincerity seems to prevail. “There’s also a danger that it becomes this thing, that you’re constantly seeking this validation, that you’re trying to do something to get a particular response. I don’t like that type of acting ... Bad acting is being self-aware, being self-conscious.”

Other actors, he adds diplomatically, can play the awards game and not be contaminated, but not him. “The only approval I seek is the director’s.” This desire to please leads to anxiety, he confesses. “You want to get it right. You want to achieve what the director’s vision is.”

Some have suggested Phoenix is something of a muse for Anderson. Does he feel that? He shrugs. “I’m just an employee. I think I’m just another actor that he’s working with. You should ask him.”

When I do, later, Anderson laughs. “Oh, that’s funny. That’s a sweet answer. He inspires me, for sure. He makes me want to be a better director. He’s endlessly inventive, not afraid to chase down horrible, dead-end, bad ideas.” The director declines, however, to have a bearded muse. “Muses should be more like Joanna Newsom,” he says, referring to Phoenix’s harp-playing co-star. “That’s a muse.”

Humble employee or not, I ask Phoenix whether Inherent Vice signposts the fracturing of counter-culture and the arrival of a darker, more paranoid era. Pacing again, he launches into an answer, then drops his cigarette. It comes to rest, smouldering, under a chest of drawers. “Fuck!” On cue a siren wails below, though not for the 20th-floor would-be arsonist. The A-lister gets on his knees and after some rummaging extracts and extinguishes it. He tries to resume his train of thought, then stops.

“Hey, listen man, I don’t know that I think about that. I’m an actor, not a writer. There’s a danger sometimes, when you think about the broader themes of a story, you start winking at the audience: ‘Hey, this is a metaphor.’ I see it in performances where the actors are hyper-aware of the statement the film is making and they start selling that.” Phoenix does not, alas, name and shame.

He is deft at playing unhinged characters, such as emperor Commodus in Gladiator, or unmoored ones, a pattern in his three most recent films. Is he drawn to personalities who feel lost? Phoenix shrugs. “I don’t think about it that way. Aren’t we all experiencing that in some ways? Isn’t everybody going through life trying to figure it out?”

Phoenix loves westerns and kung-fu films and is a fan of Iron Man. He was once tipped to play the Marvel character Doctor Strange, as well as Lex Luther in Batman v Superman, two upcoming superhero films, but the roles went to Benedict Cumberbatch and Jesse Eisenberg. “I’m not one of those cinephiles that likes watching (only) Godard and shit,” he says, adding that he would don superhero or villain Spandex if conditions were right. “I try not to have any restrictions. I’m just interested in the film-maker and the character, and something that feels new and exciting. Whether that’s a big studio movie or an independent movie doesn’t really matter to me.”

He pauses. Another inner battle against circumspection. “Obviously the more money at stake, the more expectations there are to make that back, right? So you start lowering your standards. You try to appeal to as wide a market as possible. I think that’s why typically I haven’t done bigger movies.”

He would do a franchise if done in an interesting way, he says. “In a superhero movie it’s typically good guy and bad guy, and bad guy attacks. Well, in real life evil seduces.” Phoenix has a fantasy of remaking The Last Temptation of Christ as a superhero film in which an angel tempts Christ to come down from the cross, end his suffering and start a family.

The afternoon has worn on, the sunlight is paling and Phoenix is needed for roundtable interviews with groups of journalists flown in for the occasion. A marathon talkathon answering questions that will range from insightful to inane. A notable absentee from the marketing of Inherent Vice is Pynchon. The author is so private and press averse, few know what he looks like, and Warner Bros could not enlist him for the promotion. Is Phoenix jealous?

He bolts upright. “Of course! Who wouldn’t want that?” His eyes gleam. “It sounds like the dream: to be creative and to follow your passion, and then not have to sell it, not have to translate that experience into something that’s palatable to a wide audience.” He is cheered that in the celebrity game one fox, at least, has found a bolthole. Maybe one day he will too. “Fuck, yeah!”

Inherent Vice is out in the UK on 30 January