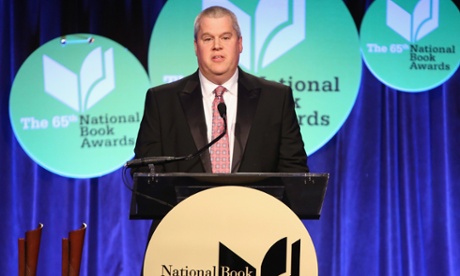

At the recent National Book Awards ceremony in New York City, presenter and bestselling author Daniel Handler, better known as Lemony Snicket, made comments intended as humorous – though widely heard as offensive and racist – after presenting an award in the young adult category to author Jacqueline Woodson. Apparently, not even a ripple of discomfort crossed the room as Handler made his comments, which centered on the African American author’s allergy to watermelon. I wasn’t present that night, but I’ve been at past NBAs and countless similar events, and can well imagine the sea of white faces turned up to the podium, the thousand white hands applauding. (Handler later apologized and contributed to a fund for diversity in children’s literature).

The matter would never have become public at all if social media hadn’t erupted during the livestream of the event: people were tuning in and listening in a way that mainstream US publishing was not, and hasn’t for some time.

The incident opens a new window onto a never-adequately-addressed issue at the heart of the US publishing industry: are American publishers as insular, clubby, and tone deaf as it often appears? Why does a truly inclusive and diverse publishing program, and a genuine appreciation of it, still elude us? Have such goals, more commonly discussed a decade ago than today, been tabled even as the country has grown steadily more diverse, supplanted by squabbles about format, pricing and contract terms with Amazon? Has our stress about the state of the bottom line pressed us back into the predictable, the homogeneous, the so-called safety of what has worked in the past; has it closed our ears to what the culture hears?

If so, we’d better think again. Because any gains in the format and pricing wars are going to be wiped out if content is less and less relevant to the way people live, who we are, and what we aspire to be. We need to fight those battles to continue to survive – but we also need to recall our broader purpose.

Most literary professionals I know understand very well that books are great equalisers and boundary-crossers, and that the act of reading is not gerrymandered by race, culture, or market niche. We know that the best books (many of which survive without fanfare on publishers’ backlists) can unify where politics divide; that they soften animosities, build bridges, produce solutions. Books are our teachers and truth-tellers when others fail to prepare us for the world as we find it.

Books return us to ourselves. They offer a quiet flow of information, insight, alternatives, and respite. These qualities have always been the trump card of the form, and an army of writers, librarians, editors, booksellers, reviewers, teachers, sales reps, and readers have fought for these values over time, in every format – from goatskin-bound folio to electronic file. Scratch the surface of the most hard-bitten publishing executive and you’ll find someone who got into the business because he or she was touched by a book (quite possibly even one by James Baldwin or Toni Morrison).

That’s why publishing’s hands come together to applaud, in spite of the occasional obtuse blunder by one of our own. We feel that we are colorblind to a good story well told; that our best selves protect us from our weaknesses and omissions – even from our ignorance. But, paradoxically, it is our very faith in what books can accomplish that often blinds us, makes us lazy or complacent, or forget what it was we came here to do.

It’s time to remember. As we go forward, biblio-diversity, innovative content, and listening to the culture as well as speaking to and about it will be necessary for publishing’s ecosystem. Inclusiveness need not be about filling quotas or celebrating worthy exceptions, but of returning to our core values, time-tested and forged by our strengths. Such publishing requires a certain fearlessness, rigorous instincts and political courage. Even in the press of business, we should continue to cultivate our faith in what books and publishers do best.