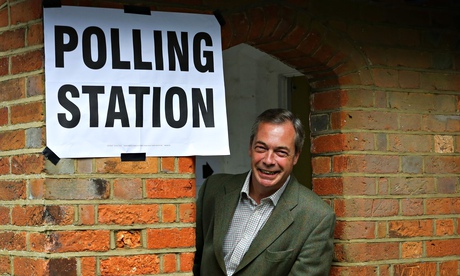

It was the year Ukip truly arrived and Scotland nearly left. As the parliamentary recess approaches, British politics feels violently unpredictable – at least one seat at the 2015 election could be a five-way marginal. With that in mind, it’s not surprising that the first big politics book of the year was Rob Ford and Matthew Goodwin’s Revolt on the Right (Routeledge), a sparky academic study of the rise of Ukip. The book charts the party’s humble origins from its founding in 1993 – in the office of a history lecturer at the London School of Economics – through a decade of byelections where it only managed to average 1.7% of the vote. (It now regularly records figures in the mid-teens in national opinion polls.) Ford and Goodwin make the case that Nigel Farage has achieved something remarkable by turning a single-issue pressure group into a full-scale party. Their key insight – that Ukip appeal not to the left or right, but to the “left behind” – is now conventional wisdom.

Also released in March was Roy Jenkins (Jonathan Cape), John Campbell’s authorised biography. A sharp, carefully researched work, it balances admiration for its subject’s considerable achievements – overseeing the Abortion Act as home secretary, for example – with a clear-sighted look at his personal foibles. It was as popular with reviewers on the right as the left, and also contained the unexpected revelation that the man who legalised homosexuality had himself had a passionate gay relationship at university (with his future cabinet colleague Tony Crosland).

There were no such shenanigans in the second volume of Alan Johnson’s memoirs Please, Mister Postman (Bantam), although the former home secretary retained the wit and self-deprecation that readers loved in his first book, This Boy. There is a little too much about the internal machinations of the Buckinghamshire postal service in the 1970s, but Johnson’s charm makes him easy to forgive. Meanwhile, if it’s tales of old-school heroines you’re after, turn instead to Baroness Trumpington’s autobiography, Coming Up Trumps (Macmillan). Two facts tell you everything you need to know about this uniquely British character: she worked at Bletchley Park during the second world war, and in 2011 she flicked a V-sign from her House of Lords perch at a fellow peer who referred dismissively to her age.

At 92, Baroness Trumpington is only just the oldest person on this list, because the summer saw the publication of Harry’s Last Stand (Icon) – a moving first-person account from 91-year-old Harry Leslie Smith of growing up before the creation of the welfare state and NHS. Making a simple, emotive case for progressive politics, Smith was the star turn at this year’s Labour party conference.

In July, the jailing of Andy Coulson, David Cameron’s former spin doctor, prompted the release of a rash of books which had been waiting on the verdict. The best is Nick Davies’ Hack Attack (Chatto & Windus), written with the pacing of a thriller and all the insight you’d expect from the reporter most intimately associated with the case. Owen Jones’s The Establishment (Allen Lane), published in September, built on these themes, exploring how the police, media and politicians amass and retain their power. The combative interviews with Jones’s political opponents, such as the libertarian blogger Guido Fawkes, are worth the price of admission alone. Similarly not recommended for those with high blood pressure is James Meek’s Private Island (Verso), which chronicles in loving detail the way our public services have become engines for private profit.

For those who prefer the long view, there is Modernity Britain (Bloomsbury), the latest instalments of David Kynaston’s epic history of Britain. The most recent volumes cover the late 1950s and early 1960s and their collage-like style – told through newspaper clippings, TV listings, and other ephemera – is in equal parts dazzling and dizzying.

And for fans of big egos, there was plenty of choice in the bookshops this year. First up, Russell Brand’s much mocked Revolution (Century), the book that launched a thousand op-eds, followed swiftly by Boris Johnson’s biography of Winston Churchill, The Churchill Factor (Hodder & Stoughton), in which the London mayor tried to recast the wartime leader as a 1940s version of himself (or possibly vice versa). Both books provide a salient demonstration of what happens when a writer is Too Big To Edit: Johnson gets away with describing Churchill as the Tories’ “biggest cheese”, and his opponents as “Stilton-eating surrender monkeys”, while Brand doles out sentences such as: “The significance of consciousness itself as a participant in what we perceive as reality is increasingly negating what we understood to be objectivity.”

The year closed on a lighter note, with several stocking-fillerish contributions for the politics nerd in your life. First up is Would They Lie to You? (Elliott and Thompson) by Bloomberg reporter Rob Hutton, which explains the strange language politicians feel compelled to adopt. (Example: “technocrat – someone who understands the subject, but whom I wish you to ignore. Antonym: ‘independent expert’.”) Then there’s Philip Cowley and Robert Ford’s Sex, Lies and the Ballot Box (Biteback), a collection of essays on all kinds of fascinating trivia, from the reasons why wannabe councillors should change their name to Aaron Aardvark to explaining why men seem more knowledgeable about politics than women (answer: they’re bluffing). Finally, there is Guardian political sketchwriter John Crace’s I Never Promised You a Rose Garden (Bantam), a satirical account of the bizarre world of coalition bickering.

And if all that sounds like too much reading, you could always ingest your politics in visual form with Martin Rowson’s scatological The Coalition Book, featuring all the drawings of David Cameron in purple lacy bloomers you could possibly want.

• Save at least 20% on these titles from the Guardian Bookshop. Visit bookshop.theguardian.com or call the Guardian Bookshop on 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p on online orders over £10. A £1.99 charge applies to telephone orders.