I’ve been a big Bret Easton Ellis fan since the release of his debut novel, Less Than Zero in 1985. Written in a semi-autobiographical style, and based on his own adventures at university, the book is a drug-fuelled romp through a degenerate Los Angeles. He didn’t break any new ground with the follow up, Rules of Attraction (1987), which felt like retreading ground he had already visited, but then he quickly broke those boundaries with American Psycho (1991). It was here that the presence of his more satirical voice became stronger and stronger, more dominant in amongst the obviously improved sense of narrative control.

His characters were all terrible people: cold and vacant, lost in the consumerism of their own version of New York, but none more so than the novel’s extravagant centre, Patrick Bateman. Where most novels are concerned with delivering a protagonist that the reader is compelled to associate with, to try and understand, Bateman is a monster with a nice business card. He’s dressed in suits that he explicitly talks about, going into terrific detail about every thread, picking them out with delicate precision. His relationships, his drug use, his slightly demented sexual encounters – all are sold as the products of his job (which is what, exactly?) and the crude balance of his social group – identical businessmen with their identically drug-dependent girlfriends.

The satire reeks in the way that the best satires do, being both familiar, and straddling a line between discomfort and humour. We can all recognise these people, even now, nearly a quarter of a century after the fact. But where Easton’s finest work comes is in the ways that he pushes Bateman – who nearly shares a name, only one vowell removed, with Batman, that other mild-mannered businessman by day, psychopath by night – into the realms of the extraordinarily horrific. Driven by something unspoken – Bloodlust? An emotional reaction that runs somehow deeper, nastier, less predictably? – Bateman kills people with an almost indiscriminate sense of right and wrong, taking the lives of those who he encounters and finds opportunity to murder.

And those murders are truly grotesque, butchery and torture strung together in long sequences of unflinching chaos. Bateman doesn’t look away, and neither can we. At their worst they represent some of the more unsettling writing that one can encounter, but not actually because of the content. Of course, that’s terrifying – Ellis’s mastery of language alone guarantees that, his descriptions crude and brutal – but the coldness with which they’re delivered separates them out from more conventional horror literature. Throughout the text, we also dance with this vague idea that the truth of Bateman’s life is somehow wavering; that we’re being told what he sees as reality, when there’s a good chance that nothing he believes is real – that the murders, the atrocities that he commits, the only things that seem to pacify him in this world he inhabits are actually false, lies and psychological breaks.

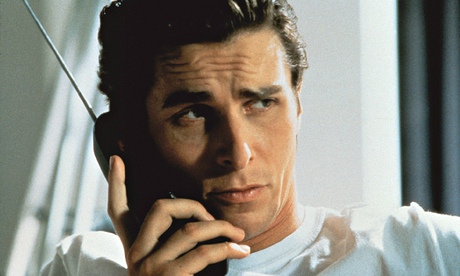

Crime scenes he’s decorated with blood disappear; people that he has killed come back into the text, sliding back to life in ways that aren’t some horror movie cliche, but more a simple reappearance. Throughout the book, the other players in Bateman’s life are introduced as being people other than who they are, identity confused with status and role. Nobody is ever who they initially seem. (This idea was taken further in Ellis’s subsequent novels, with Glamorama (1998) pushing the idea to its natural conclusion, wherein a main character is confused with a celebrity – in that case, a superbly prescient inclusion of Christian Bale, still two years away from playing Bateman in the unfairly maligned Hollywood adaptation of American Psycho.) Bateman is this taken to the ultimate conclusion. He’s a fantasist, and a murderer.

But make no mistake, Bateman is a horror villain. He’s up there with Big Brother, with Pennywise, with Hannibal Lecter. Famously, horror villains wear masks. It’s what makes them all the more terrifying to us, because we can’t see past them. They present themselves as being part of the normal before surprising us. Upon first reading, it’s easy to see Bateman as exactly this: a psychopath beneath this veneer of a businessman. But the novel’s more satirical nature leads us to see the supposed ordinary people of this novel as awful examples of humanity. Bateman isn’t hiding: he’s a murderous villain in plain sight. Horror novels usually rely on the veil of normality being lifted from the villain, exposing them for what they really are. The true genius of the horror in Ellis’s book isn’t that said veil is lifted. It’s that it isn’t even there to begin with.