“Beware of the agapanthus,” read a sign at Faringdon, the famously idyllic Oxfordshire home of the composer, novelist and aesthete Lord Berners. But it wasn’t the garden of which visitors – the glittering roll call included Gertrude Stein, Nancy Mitford, Igor Stravinsky and Salvador Dalí – needed to take care. In its heyday, Faringdon was a noted weekend haven, a stage set on which guests were invited thoroughly to enjoy themselves so long as they remembered always to play a suitably witty role. However, beyond the jokes and the ice-cold martinis could be discerned a fierce tinge of pain, the prime cause of which seemed mostly to be Berners’s younger lover, Robert Heber-Percy, aka the Mad Boy. It was this creature, dashing but often cruel, whom one had to approach with caution.

Heber-Percy was the writer Sofka Zinovieff’s maternal grandfather, and in her new book she tells the story of how she came to inherit Faringdon on his death in 1987 (she was then a 26-year-old anthropology student living above a shop in the Peloponnese). But to get there, she must first present us with a series of portraits: of the eccentric Berners, who kept a clavichord in his car and dyed his doves turquoise, pink and gold; of Heber-Percy, who cared nothing for books or music, preferring instead to shoot, to ride and to drink; and of Jennifer Fry, the society beauty whom Heber-Percy unaccountably married in 1942, 11 years after his arrival at Faringdon. (Fry’s daughter, Victoria, is the author’s mother, and among those Heber-Percy bypassed when he chose her as his heir). Yes, as family sagas go, this one has everything: money, sex, secrets, bad blood. There is even a terrifying Mrs Danvers figure in the form of Rosa Proll, Faringdon’s Austrian housekeeper.

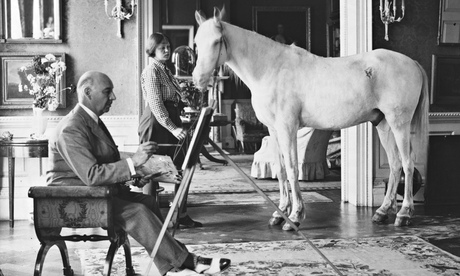

At its heart, though, is a riddle: what kind of man was Heber-Percy, and why did he act as he did? Zinovieff did not meet her grandfather until she was 17, by which time Gerald Berners had long since passed into legend (He died in 1950, and was widely memorialised, most notably by Nancy Mitford, who wrote him, in the form of Lord Merlin, into her novel The Pursuit of Love.). Was their relationship a love affair? Zinovieff believes it was. But relationships, at least among the upper classes, were then more flexible than now, and theirs stretchier than most. If Gerald’s friends were astounded when he took up with Heber-Percy, who at 20 was almost three decades his junior, they were even more amazed when this handsome “ape” brought home a wife. What had happened? Had the couple taken too much champagne at the Gargoyle Club? Gerald, on the other hand, took in his stride both the marriage and the baby that arrived nine months later. If Penelope Betjeman could bring her horse to tea, why shouldn’t Robert install a child? Perhaps, too, Victoria was a useful distraction, a way of keeping his depression at bay. Photographs of the trio plus baby taken by Cecil Beaton at Faringdon in 1943 cast Berners in the role of benign grandfather.

Nevertheless, the menage was doomed. Jennifer was shocked to find that she and her husband would not be lovers; during their honeymoon, she knocked on his bedroom door in vain. In the overheated landings of Faringdon, his coldness and anger came at her like a slap, and by 1944, she was gone, her baby with her. She left behind just one thing: a fish-shaped wicker handbag that sits on a gilded chair in the house even today. Robert was always involved with his daughter, but between them there grew a kind of animal loathing, visceral and incurable. Ultimately, Victoria’s rejection of him extended even to Faringdon. She brought up her own family in Putney, her ideals more hippyish than debutante.

It isn’t Victoria, though, that most intrigues the reader; nor is it the elusive Jennifer, whose subsequent lovers included Henry Green, Cyril Connolly, and the poet Alan Ross, whom she married. And Berners’s story has already been told, admirably, in a biography by Mark Amory. No, it’s the Mad Boy who fascinates. He is so beautiful, and yet his behaviour is so ugly. After Berners’s death, he is stricken, at sea. “I never made any decision without either mentally or actually considering his reaction,” he wrote to Osbert Sitwell. “I feel quite lost…” But, determined to keep Faringdon’s spirit alive, the entertaining continues, and he installs a preposterous pink bathroom, with tropical mural. Emerging from grief, his love life is as muddy as ever. There are two men, Hughie and Garth, and another baffling marriage, to the elderly Coote Lygon, who grew up at Madresfield, the house that inspired Brideshead Revisited. (“A Darby and Joan engagement just announced in the Times has led to much chuckling on the grouse moors this week,” said the Daily Express.) Coote was girlishly excited to be a bride – and crushed to be banished to a nearby bungalow soon afterwards.

Zinovieff tells this extraordinary tale with great care: she makes no judgments, but nor does she look away when bad behaviour occurs. When she arrives at her own place in the story, she grows more reticent, but I suppose this is understandable: if she makes too much of the horror she at first felt at her inheritance, she risks sounding ungrateful. The result is a book that is unputdownable and – thanks to her publisher – gloriously lavish, something fascinating to gaze at on every page. In my favourite photograph, the designer Elsa Schiaparelli and Lord Berners are standing at the top of the 100ft tower he gave to Robert as a birthday present in 1935, a building often described as the last folly in England. Gerald is in a shirt and tie; Elsa is wearing a turban. They look delighted, with the view and each other. That weekend, the “Schiap”’s fellow house guests included HG Wells and Tom Driberg. I bet the conversation was devastating.

The Mad Boy is published by Jonathan Cape (£25). Click here to buy it for £20