Death of A River Guide (1994, published by Atlantic in 2004)

Flanagan’s first novel is narrated by its hero, river guide Ajaz Cosini, as he drowns in a wild Tasmanian river while the tourists he has been leading look on helplessly. Memories of his own life and visions of his ancestors and their violent colonial history crowd in as the water rushes over him. “If Flanagan hasn’t yet produced the Great Tasmanian Novel, he has made a powerful case that such a book – scary, violent, tragic and beautiful – would be worth reading,” said the New York Times.

Gould’s Book of Fish (Atlantic, 2002)

Flanagan’s third novel was the one to bring him global attention. Beautifully produced, with images by the convict artist William Buelow Gould, it tells the story of a 19th-century forger and thief who is sent to Tasmania’s Sarah Island where he obsessively paints the local fish. Alex Clark in the Guardian called it “one of the most fatiguingly inventive novels to have been published in recent years”; it won comparisons to Sterne, Melville, Joyce and Faulkner but was described by one critic as a “monstrosity”. The book is full of horrors – Aboriginal massacres, prison tortures, a demented camp commandment who uses the handily available slave labour to build a railway to nowhere, in an intriguing foreshadowing of Narrow Road to the Deep North – but is also a rollicking hymn to the “beauty and wonder” of the cosmos.

The Unknown Terrorist (Atlantic, 2007)

This is Flanagan in more conventional mode, with a thriller “that is genuinely thrilling” in which a Sydney lap-dancer catastrophically crosses paths with a possible al-Qaida operative. “Flanagan organises conspiracies and manages chases with the skill required by the genre but his real interest is in weightier matters,” wrote Peter Conrad. “This is a novel about the state of a nation, and it apostrophises Australia with a rage that derives from betrayed love … [the characters’ venality] makes moral cowards of them, and the government terrorises them into brown-tonguing Bush by appealing to their economic anxiety and to their skulking xenophobia.”

Wanting (Atlantic, 2009)

In his fifth novel, Flanagan returns to the 19th century and what was then known as Van Diemen’s Land: a remote penal colony where the island’s governor, Sir John Franklin, has adopted an Aboriginal girl, supposedly to civilise her. The narrative cuts between Tasmania and London, to sketch a vigorous portrait of Charles Dickens, who wrote and starred in a play about Franklin’s disastrous polar expedition. “With terrific brio and aplomb,” wrote William Boyd in the New York Times, the book demonstrates “how fictionalising history and real people can pay great dividends”.

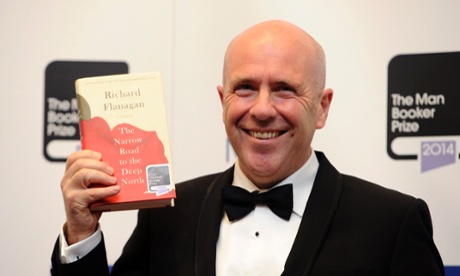

The Narrow Road to the Deep North (Chatto & Windus, 2014)

Flanagan’s Man Booker winner is “a grand examination of what it is to be a good man and a bad man in the one flesh and, above all, of how hard it is to live after survival”, wrote Thomas Keneally in his Guardian review. Twelve years in the writing, it vividly conveys the experiences of Australian prisoners of war forced to work on the Thai-Burma “death railway” during the second world war, and of their Japanese captors. Peter Carey, who said his generation of writers hadn’t engaged with the soldiers’ suffering, hailed it as a “really, really important” moment in Australian literature.