Much as I like Henry Miller’s writing, it’s his life I really love. I discovered him at a very useful time. I was in my early 20s, had just left drama school, and everyone was telling me that acting was a stupid thing to do – there would be no job security, it wasn’t going to work out. Just when I was thinking they might be on to something, I discovered Miller.

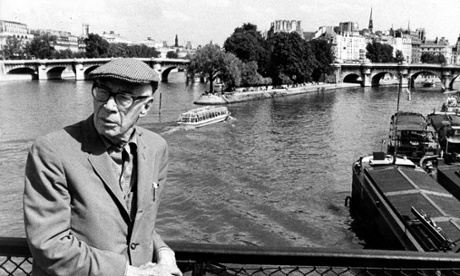

He was born in New York in the 19th century and in 1930, halfway through his life, he decided to start again. He left everything – his family and his no-hope job at Western Union – and reinvented himself as a writer in Paris. His first book, Tropic of Cancer, wasn’t published until 1934, so for four years Miller lived below the poverty line, the classic starving artist. But he was happy. There’s a great quote of his: “I have no money, no resources, no hopes. I am the happiest man alive.” He’d started again on his own terms. As a young man, I found huge inspiration in that.

Let me get the caveats out of the way. God knows, there is no writer on Earth more in need of an editor. And Miller certainly has a case to answer when it comes to misogyny, not just through our 21st-century eyes, but even by the standards of his time. Yet Miller is still the best writer I know when it comes to describing the pure, visceral thrill of standing on a street corner, not knowing what the day is going to bring, the thrill of being alive and optimistic. That appealed to a young kid in a leather jacket, wondering whether he’d made the right career decisions. And it still appeals.

There’s something admirable, too, in the absolutely uncensored version of himself that you get through Miller’s writing. I don’t condone everything he says, but then I don’t think anyone could condone everything someone said, if they were honest all the time. With Miller, you don’t just get warts and all, you get abscesses and cancers, too.

He had an extraordinary meeting with George Orwell, who had loved Tropic of Cancer. In 1936, on his way to fight in the Spanish civil war, Orwell stopped off in Paris to say hello. They sat down in Miller’s flat, and the first thing Miller said was something like: “Why are you going to a war that is not your business, when you can be much more useful to your species by staying alive and writing? But I love your work.” And Orwell replied: “You are, by doing nothing, helping the fascist cause, and they will shoot your head off the minute they get power. But I love your work.” At the end of the afternoon, Miller gave Orwell a coat to wear through the winter on the Spanish front – and they never met again. There’s surely a one-act play in there.

Miller also led me directly into my other great passion, aside from acting, which is collecting and dealing rare books. I started to investigate how Tropic of Cancer, with all its purple passages, could possibly have been published in 1934. It wasn’t published in the US until the 1960s. That led me into the French publishing world, and to Paris in the 1920s and 30s – easily, by some distance, the place I would most like to take a time-machine to. The first edition of Tropic of Cancer was the first big book I bought as a collector: I got it home and cried at how much I’d spent. But now I can’t think of anything better to collect. As individual things, books are beautiful. But when you put them all together, they contextualise each other. Together, books tell a story they can’t tell apart.

Henry Miller in brief

Born: 26 December 1891, New York.

Way in: With his first novel, Tropic of Cancer.

Key work: As above.

Henry Miller in three words: Priapic. Prolific. Polarising.

• Neil Pearson is in Waterloo Road, on BBC1 at 8pm on 22 October.