Musical biopics tend to fall down when we see the actors trying to replicate the characteristics the star they are playing is famous for. If the focus is on what an artist did in the studio or on stage, we soon lose interest. Why would you want to watch someone who neither looks much like the musician they are ostensibly portraying, nor sounds much like them, do very little apart from play songs you know by heart? If that’s what you want, you can get more of a thrill from going to see a tribute act. So there has to be a backstory, something to lift the subject to mythic level – and being mythic is key.

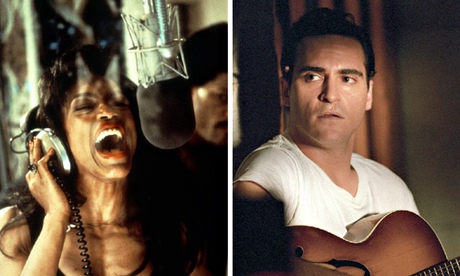

Hence, the thoroughly enjoyable Walk the Line isn’t the story of a pill-popping philanderer who finally gets his life together; it’s Johnny Cash and June Carter’s indivisible love in the face of enough demons to fill a horror movie franchise. What’s Love Got To Do With It isn’t about a woman who marries a domestic abuser and eventually gets round to leaving him. It’s Tina Turner’s epic struggle against adversity to achieve triumph. In the music biopic, every struggle has to be epic, every demon has to be fought, every triumph has to be in the face of popping flashbulbs.

Of course, musicians’ lives, like everyday lives, aren’t really like that. And, paradoxically, arguably the best music biopic is one that steadfastly refuses to romanticise either the struggle or the outcome. Anton Corbijn’s portrait of Ian Curtis, Control (right), shows him at his day job, or in his suburban home, or being an uncommitted father and husband. Even as Joy Division become popular, there’s no triumph. His death, when it comes, is not elevated into a substitute for the crucifixion: it’s all the more tragic for being so real.

The documentary ought to be a better way to present the truth – a truth – about a musician or band. And the best of them – the Ramones film End of the Century, the Chet Baker documentary Let’s Get Lost – do provide a vivid insight, especially to fans (and it’s for fanbases that most documentaries are made). Yet so often they take the exact opposite tack to feature films. Instead of being tales of heroic struggle, they tend to present the life of the musician as being generally pretty crummy (or else, in the case of superstar bands, they are bland, officially endorsed films, telling a partial version of the truth). The big crossover rock doc of recent years, Anvil! The Story of Anvil, took the isn’t-life-as-a-musican-awful trope to its logical conclusion, affectionately showing the hapless Canadian metal band rocking on in the face of an almost complete lack of public interest. Had it not been such an extreme example of the form, of course, no one would have bothered watching it in the first place. After all, a film about a band only half a dozen people have heard of, let alone heard, is a hard sell without turning Anvil’s failure into a failure beyond compare, a failure so catastrophic it has to be seen to be believed.

It’s an oddity that the artform that can most vividly convey the excitement of music is the one that is freed from the problem of having to actually play you the music. The person seeking to understand the phenomenon of Jerry Lee Lewis is better off bypassing Great Balls of Fire, starring Dennis Quaid, and heading instead for Nick Tosches’ highly impressionistic 1982 biography, Hellfire, in which the stew of sex, booze, faith and music in the deep south is brought vividly to life, and which will send you racing back to the original songs. Ditto the Beatles: if you want to grasp what being Lennon or McCartney or Starr or Harrison was like at the height of Beatlemania, read Michael Braun’s Love Me Do: The Beatles’ Progress, which will tell you more than any documentary. And if you want to know what made their records such unparalleled landmarks in pop history, go to Ian McDonald’s Revolution in the Head, rather than the Anthology documentaries.

Music is at its most exciting when it fires the imagination. And that’s what writing at length about music, at its best, can do. Without drab talking heads on screen, or some badly recreated gig on a studio soundstage, your mind and the words on the page can take you to the most hyperreal version of reality. Compare the tellings of Altamont in the Maysles brothers’ film Gimme Shelter and Stanley Booth’s The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones, a rare case where you can both see the events on screen and read the same incidents on page. The Altamont of the Maysles looks like somewhere you’d want to leave; Booth’s version is a hell you would never have wanted to enter. That’s the power of words and music.