Welcome to the Mount Washington Hotel NH, the biggest all-wood edifice in New England. It's July 1944. Over in Europe, allied forces are grinding across France. Down in Washington DC, summer reigns steamy, torrid, unending. But here the air is cooler, the grass greener. Some 730 delegates, assistants and bag carriers from 44 countries throng the hotel lobbies; 500 journalists bus in daily to keep them company. Rivers of booze flow in every bar and restaurant. The food, piled high, is a heart attack on a plate. Cardini, master magician, does his sleight-of-hand cabaret stuff. Pretty girls (many of them attached to the Soviet delegation) have an odd propensity to knock on powerful strangers' doors and offer secretarial services of no very clear specification for no very evident reason.

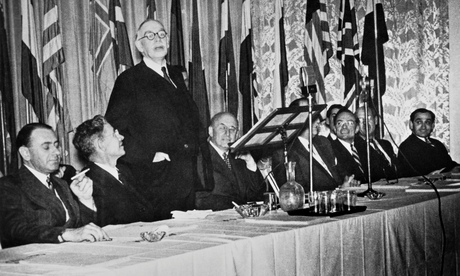

And, at the heart of the action, locked in confrontation week after week, stand two proud champions of their respective nations. It's Lord John Maynard Keynes, of Bloomsbury and Britain, the greatest economist in the world (though probably also the world's worst chairman) versus Harry Dexter White, leading for Uncle Sam, both of them striving to deliver the Bretton Woods agreement, essential architecture of a new global economic order.

Is that Lady Keynes (aka Lydia Lopokova, retired prima ballerina) exercising her splendid legs in the bedroom upstairs, or rummaging openly in her cleavage for a missing door key? Is that Harry White sneaking off for tea and probably more than sympathy in the Russian camp? Who's weighing the 10 tons of wastepaper as draft after draft is torn up and thrown away. Tonight Lord and Lady Keynes are scheduled to sing The Blue Danube for an eager lounge audience while Harry White delivers his own hot favourite: "When I die don't bury me at all/ Just cover my bones with alcohol."

This is the summit to top the lot, a raucous, rollicking, exhausting, even death-dealing experience. But it is also a true turning point in history. Enter the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and decades of growth and recovery. Agreements don't come much more momentous than this.

Ed Conway has written a vivid account of these Bretton Woods encounters, high and low, as well as chronicling what came before it (the corrosive debacle of the Paris summit that followed the first world war and laid the foundations for the second) and what came after (politicking, suspicion, delusion and eventual disintegration). And his summit tour makes the issues at stake in Mount Washington lucidly clear.

The old gold standard that briefly brought order in the late 19th century was long gone, leaving only chaos behind it. Somehow the world of commerce had to find settled patterns for economic coexistence again. Somehow Europe – and especially Britain – had to dig itself out of the black hole of debts it could never repay (including those to evaporating colonial empires). But would America, already the only real economic superpower, take a lead role in reconstruction? Would the Congressmen on the Hill see where their best interests lay? And would British opinion, led by a bombastic Lord Beaverbook and affronted Bank of England, finally recognise that the imperial game was well and truly up, that in four or five years we would "have to close up shop", as one bleak summit stalwart put it?

This is a ripe, resounding story, brilliantly told: but it is also much more than just a story. In one sense, the human detail – especially of sick, debilitated Keynes's final months cadging loans from stony-faced US treasury secretaries, struggling to buy his bankrupt country time – seems out of place amid careful recitals of what was debated and resolved, who won and who lost. We're not supposed to see economic theory in personal terms, surely? Or to mix the lofty, seemingly quasi-scientific laws of which policies can and can't be attempted with the grubby evasions of politics?

But here everything swills together. Keynes isn't always right. He is often wrong – or, at least, wholly impractical. He knows what should be done – that the IMF should be called (and act like) a bank not a fund, that it should enable recovery not police it – but he doesn't have the clout to insist because Britain itself has only puny leverage left. Put gold and any remote standards of linkage aside? No, says Harry White, Congress won't stand for that. So the ingots in Fort Knox are loosely yoked to the dollar which, in turn, becomes a global currency (with the Fund and the Bank both inevitably kitted out as tame US institutions).

This isn't pure economics – or, indeed, pure anything. It is what, these days, we might deludedly call the will of the "world community", country after country haggling and manipulating for best narrow advantage. There's precious little idealism on show and a wealth of self-interest. (Why bother with gold when we have so much silver, the Mexicans at Mount Washington keep asking in the bar.) But don't sneer too hard. Somehow, out of this often rancid stew, the summit of '44 created the underpinning of a world order that, for a while, brought happy days again. And somehow, three years later, undreamed of amid the wheeling and dealing in New Hampshire, George Marshall unveiled his quite separate plan.

Ed Conway makes those distant achievements fresh again with scholarship and verve. This is living history: and a seam worth mining further. Next, perhaps, he might try the birth of the euro, with smelling salts as well as cognac unlimited?