Alfred, Lord Tennyson, published 1854

How do we understand and enjoy poems? By using our ears as well as our eyes. By realising that sound communicates meanings and feelings. With this in mind, Richard Carrington and I set up the Poetry Archive, a continually expanding online audio library of poets reading their own work. Listen to Tennyson, one of the first poets to be recorded, by colleagues of Thomas Edison, in 1890. In the surviving fragment you can easily hear how his chanting, pausing and Lincolnshire accent all contribute to the poem’s presence and power Photograph: Ronald Grant Archive

Siegfried Sassoon, 1919

No recordings were made of poet and decorated soldier Sassoon in his early days, but a handful were done later, and the last shortly before his death in 1967. It’s at once shocking and salutatory to hear how the first world war continued to shadow his mind throughout his long life, and very moving to hear his sadness and exhilaration in the beautiful short lyric Everyone Sang, in which he celebrates the war’s end: “… O, but Everyone / Was a bird; and the song was wordless; the singing will never be done” Photograph: George C. Beresford/Getty Images

Edmund Blunden, 1928

Sassoon’s friend and contemporary Edmund Blunden, whose war poems are less widely celebrated than Sassoon’s but have their own wise authority, also recorded some of his work long after the war ended. In Concert Party: Busseboom he makes some comments about the circumstances in the poem. He says “the poem relates to the London Division concert … within sight of the battlefield … not far from Ypres”. This helps us locate ourselves in relation to its story, but so in a different and even more compelling way does Blunden’s voice, speaking across the years as if today were yesterday, and matching the horror with the gentleness of his delivery Photograph: edmundblunden.org

WH Auden, 1940

We tend to think that dead poets all spoke with posh accents, as though the grave were a kind of RP training ground. But of course this is nonsense, as the Tennyson recording reminds us. If only we could hear Wordsworth’s Lake District burr, or Keats’s cockney! Or Hardy, or Housman, or any of the others who could have been recorded and never were, and now are lost to us ever. Still, we can be grateful for what we have, and WH Auden, who began speaking with a flat A after moving to the US in 1939, exploits his vocal range in his readings. It creates a tension between what he was given at home and what he discovered away from it, and underlines at least one of the themes in this poem. Listen especially to how he says "vast" and "fast" in the marvellous last verse Photograph: Alamy

Elizabeth Bishop, 1965

When I started reading poems seriously in the mid-1960s, the general view of contemporary American poetry was that Robert Lowell was driving the bus, John Berryman was wandering up and down the aisle, and Elizabeth Bishop was sitting quietly at the back. But quietness can turn out to be loud – or resonant anyway, and now by common consent, Bishop is in the driving seat. Her recitation of Filling Station – self-deprecating, nearly throwaway – tells us a great deal about her late style. And for all its modesties it is absolutely mesmeric and authoritative Photograph: Charles Rotkin/Corbis

Parliament Hill Fields 1961

How could Sylvia Plath not be included on a list such as this? The electrifying voice (light in its youthfulness, dark in its hauntedness) and the astonishing poems (at once deeply preoccupied with things of this world, and always looking beyond them) are among the most memorable sounds of the last century or so. In Parliament Hill Fields, her narrator speaks about “the grief caused by the loss of a child” through miscarriage – a subject that may not provoke the same rage and terror as Lady Lazarus, but is extraordinary all the same in its representation of grief and stoicism: “nobody can tell what I lack” Photograph: Everett Collection /Rex Features

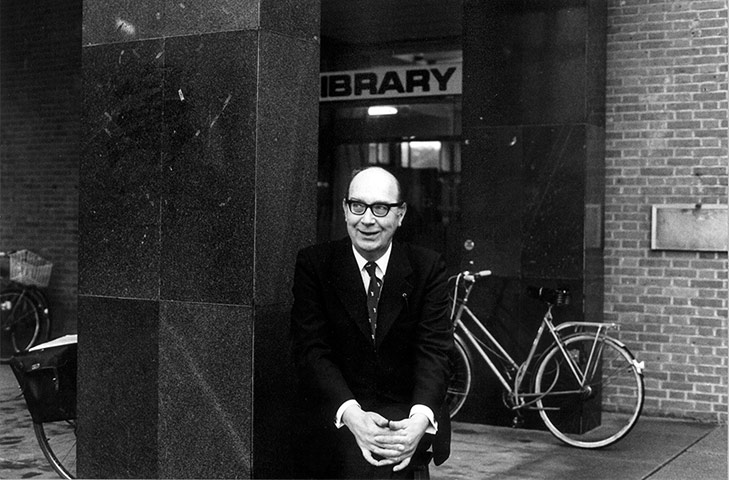

Philip Larkin, 1967

Sometime after Larkin’s death in 1985, it turned out that his friend John Weeks had recorded him reading his poems over a series of Sunday afternoons in the early 1980s. Larkin’s voice has a welcoming kind of relaxation about it – perhaps not surprising, given the affable circumstances of the recordings – but also a meticulous address. In his almost Elizabethan lyric The Trees, this takes the form of a well-controlled drama, in which tenderness is combined with something akin to clarification and even explanation. Typical of Larkin to be so simple-seeming, while touching our hearts so deeply Photograph: Jane Bown

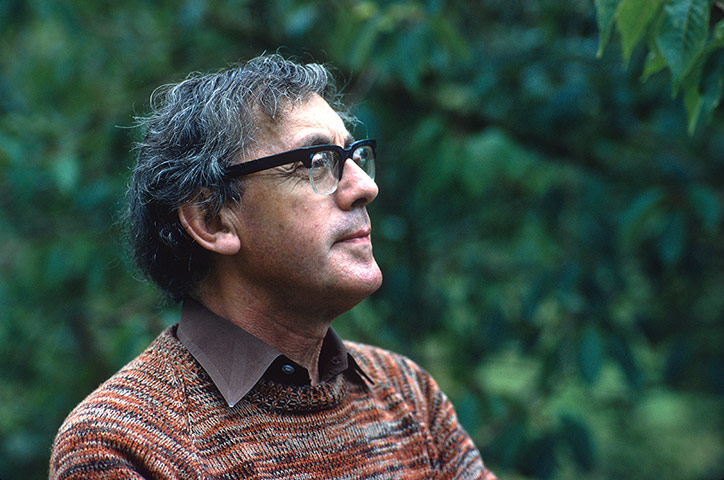

Derek Walcott, 1971

We think of the St Lucia poet Derek Walcott as someone who achieves his extraordinary richness of effect by using a language that is itself very rich. And often this is the case. Yet in one of his finest poems, Sea Canes, density and voluptuousness are balanced by a straightforwardness that is close to shocking. And at the same time this 2007 recording is very moving, certainly, as he hears the canes shaking in the moonlight, and feels the flow of time and what it takes away: “but out of what is lost grows something stronger / that has the rational radiance of stone” Photograph: Graeme Robertson

Charles Causley, 1988

My archive co-founder Richard Carrington made this recording very near the end of Causley’s life; it seems probable that Causley never again spoke his poems aloud. This gives his recitation poignancy; Causley is evidently saying goodbye to his own work. In this marvellous poem, which remembers or invents a childhood scene, this elegiac note is overwhelmingly present, although it is withheld and shaped with great dignity. If I had to choose one poem on the archive to keep, from the hundreds I admire, this would be it. “I had not thought that it would be like this”: that last line knocks me almost unconscious every time I hear it Photograph: Alan Hillyer/Writer Pictures

Alice Oswald, 2011

Alice Oswald’s long poem Memorial brilliantly fillets and reheats Homer’s Iliad in ways that honour the original and also strike disturbing contemporary echoes. Her delivery is almost relentlessly steady, but the effect is not to suppress the shock and thrill of her lines, only to sharpen them; the whole performance has a startlingly live feeling – facing its audience very boldly, yet intimate in its address Photograph: Antonio Olmos for the Observer