Hello, Claire here. We're going to wrap up this live blog now, though the conference continues through the weekend and you can keep up with it on twitter through #TLC14.

Highlights will include bloggers Dovegreyreader and Readysteadybook talking with writer and critic Sam Leith and Paul Blezard on Saturday at 2.35pm. You can read Readysteadybook's (aka Mark Thwaite) pre-conference provocation about the disappointments of literary blogging here.

Also up on Saturday is Mike Carey, whose fascinating live chat about his shape-shifting career, ranging from X-Men X-Men to Felix Castor and Sandman sequels, can be read here

Updated

General debate around the relationship between writers and publishers. “Out of 300 published books, we hope one will sell”, says Pringle jokingly – or not?

Accruing experience as a writer going through publishing relationships - better defining what you need from them @RebeccaAbrams2 #TLC14

— John Prebble (@John_Prebble) June 13, 2014

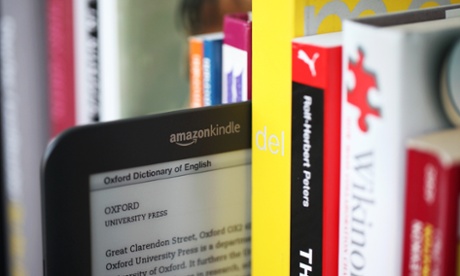

@alexandrapring: Sales of Khaled Husseini's new book were 50% in Ebook but for others it's very small. In US ebooks have plateaued. #TLC14

— Claire Armitstead (@carmitstead) June 13, 2014

Updated

"Self-publishing allows people to progress artistically. It removes the frustration of constantly sending work out and wondering if it's being read. It allows you to move on", says Baverstock. She then clarifies that she believes it can be useful to print out only a few copies of early manuscripts as a test, before actually self-publishing en masse.

From the floor: aspiring writers would have no problems with gatekeepers if they could get through the gate #TLC14. Is it harder than ever?

— Claire Armitstead (@carmitstead) June 13, 2014

Abrams: "The gate is getting narrower and narrower. How do you find the gatekeepers?"

Updated

Baverstock: "Publishers have a range of writing talent, but decisions are made depending on how promotable a work is."

Pringle says this is a sweeping generalisation: "Quality is the beginning, middle and end of why we publish a book. You can't expect all your colleagues or the world to love the book as much as you do. Personal taste has a lot to do with it... But promotability is an added bonus, not the defining factor."

Squires asks: the advantage of self-publishing is that the gate is always open, but what are the Virtues of the gatekeeping process?

Baverstock shares her thoughts as a reader: “Books are so cheap that my time matters more than my money.”

Pringle says: “The reading public is completely unaware of who the publisher is – apart from perhaps Penguin. The book is the brand, the author is the brand. How you present a book, how you package it, every bit of putting a book together has to be thought about and cared about immensely. It touches hundreds of people's lives.”

Updated

Baverstock says the industry, en-masse, is very author unfriendly. She explains that she experimented at the London Book Fair with different badges. The one that caused most averted eyes was "author".

Rebecca Abrams: One thing authors do exchange is awful publicist stories. Seldom a satisfying relationship. #TLC14

— Claire Armitstead (@carmitstead) June 13, 2014

Updated

Baverstock on social media: "Twitter is quite a writerly media – it's all about writers trying to shape sentences".

In self-publishing meetings, she says, there is a sharing that is very unusual among traditional authors. "A very common thing amongst authors is jealousy. Self-published authors get an energy from other people's achievements that is quite admirable."

Updated

Alison Baverstock says:

When well done, the role of the publisher is absolutely invisible – and that leads to authors severely underestimating the skill of the publisher." She mentions phrases like: "All you do is press a few buttons." The self-publishing revolution, in that sense, "has helped authors understand how hard editing and publishing is, and how it works."

RT @ReadHead89: Publishing done well is invisible says @alisonbav. Be careful not to equate invisibility w lack of hard work + skill #TLC14

— Guardian Books (@GuardianBooks) June 13, 2014

Self-publishing often does not mean no editor. @alisonbav research shows large proportion of writers working with editor. #TLC14

— John Prebble (@John_Prebble) June 13, 2014

Updated

Alexandra Pringle, who has worked for Bloombury for 15 years, says:

"Editors put in so much more than 9 to 5. You are investing your emotions, imagination, creativity. Also, you have to look after your authors, but your company as well. You have this push and this pull – sometimes you can't be as frank as you want to be with your author."

Claire Squires points out that this relationship is an unequal one, as publishers and indeed some agents work for more than one author, whereas for the writer there is just one publisher. Pringle replies that that would be like arguing that you can't be a parent to more than one child.

Pringle: Agent can have continuity because only needs to have loyalty to author, but publisher has to have loyalty to company as well #TLC14

— Claire Armitstead (@carmitstead) June 13, 2014

Here they all are:

Rebecca Abrams with @alisonbav @AlexandraPring & Claire Squires fab, warm talk about author-pub relationship #TLC14 pic.twitter.com/84L21ykGv1

— LiteraryConsultancy (@TLCUK) June 13, 2014

Updated

We start the session with some great passages about the figure of the publisher:

Afternoon #TLC14 Claire Squires reading vintage advice from The Business of Publishing by Charles Campbell: "The publisher is a busy man".

— Claire Armitstead (@carmitstead) June 13, 2014

Rebecca Abrams speaks: "I would have loved a long-term relationship with one publisher", but it simply hasn't happened in her career, as her books were published by either different publishers or by different imprints within the same publishers. "There's something about the longevity of the relationship: when it works, it can contain the desire for trust, the hope of being heard and seen... I don't look for it in a publisher anymore; i look for it in my agent," she says.

'I'm a thwarted monogamist' @RebeccaAbrams2 (4 editors for one novel) #TLC14.

— John Prebble (@John_Prebble) June 13, 2014

"Pick an old editor & they retire. Pick a young one & they're busy hopping between publishers advancing their career" Rebecca Abrams #TLC14

— Doug Wallace (@twittizenkane) June 13, 2014

Updated

TLC director Rebbecca Swift introduces what the panel will tackle:

"In the self-publishing environment, where you're without the agent or publisher, where does that leave the writer, and is that relationship missed? Not just its practical advantages but also its emotional and personal components. If you don't have an editorial relationship challenging you to be your best, are you being you best? And how do you know if you are?"

We're back and ready to attend the 'Mirror, Mirror, on the Wall' panel. We'll hear from Claire Squires (Professor of Publishing, Stirling University), will explore the author-publisher relationship, with Alexandra Pringle (Bloombury), Alison Baverstock(Publishing, Kingston University), and Rebecca Abrams (award winning author and journalist), who are going to debate how the digital revolution has, arguably, given more power back to the author, who now has the choice to "go it alone".

An audience member asks the speakers to reply, in one sentence, to these two questions: what are they most excited about and what are they most scared about.

- Stephen Page: "I genuinely think that opening up the conversation with readers online is the most exciting thing for publishers and writers. What I'm most scared about is the substitution of reading for other things. Doris Lessing once said thatin the Middle Ages Latin was the language of the elite, and English was the vernacular. Now we're in danger of books becoming the language of the elite and video becoming the vernacular.

- Steve Bohme: "I'm scared about the future of children's reading habits. Their access to smartphones and tablets is increasing hugely – and at same time, the time they spend reading is clearly falling. Both things are undoubtedly connected. We need to manage to assure kids will continue to read even when they use these devices all the time – the devices can also be used for reading, but will kids choose to do that?" Something else that scares him, said Bohme, is the big gap Nielsen tracked in purchasing gifts when ebook purchase rose. Basically, no one buys ebooks as gifts. "The gift market is a concern: will people still buy print books for christmas when the receivers only read on devices?"

- James Gill: "I'm scared of losing readers. Some people are just gone. I'm also afraid of a moment when there are no more books in the high streets. It's possible that, going deeper into the recession, supermarkets might stop selling books and DVDs."

- Diego Marano: "I'm excited about the potential of technology, what it can do for readers and publishers. But there must be balance and equilibrium between readers, writers, self-publishers and publishers, and this balance is at risk."

And on that note, we finish for the morning. Thanks for following our coverage and for all your questions.

Updated

There has been an interesting debate about literary fiction and how to measure it.

So literary fiction doesn't sell so well via self-publishing right now. But are those authors trying hard enough in that space? #TLC14

— Molly Flatt (@mollyflatt) June 13, 2014

'The important thing about poetry publishing is to lose as little money as possible'TS Eliot dragged into the literary fiction debate #TLC14

— Aki Schilz (@AkiSchilz) June 13, 2014

A member of the audience asks: is there any room for artistry, or is it all about commercial fiction? Page says artistry and creativity are implicit in any publishing: "without them, we have no books anyway".

And here is Cory Doctorow's keynote speech in full.

Here's our news piece detailing the data presented by Nielsen this morning: Self-publishing boom lifts sales by 79% in a year

A couple of great moments have just happened.

Page: "Editors in big companies are driving a Harley, but it's not theirs. We're more in the Vespa territory. But it's our Vespa."

And this question from a member of the audience: "Did you include data from the whole world, or just from this little island? Sorry, I'm French."

And here's an interesting fact:

#TLC14 FYI. indie authors sell by language not territory. 140+ countries available through Kobo, Amazon KDP, iBooks, Nook

— Joanna Penn (@thecreativepenn) June 13, 2014

Updated

We raise this question about new formats from DanHolloway:

Marano agrees that we will see a "new wave of writing in new formats, but predicting this is very hard – it's a world that is constantly changing."

All the speakers agree that they haven't see this trend or change yet. Page adds: "I have a feeling that there will be some activity in that direction, but it won't be the central act. Readers, ultimately, are immensely satisfied from being in someone else's head from the beginning of a book to the end of a book." Convenience to the reader should be at the heart of everyone's thinking in the publishing world, he says.

Marano goes further in saying that experimenting can be very dangerous, "you can get it right or wrong", to which Page adds that these innovations will come from writers.

Content experiment is costly. The environment isn't yet liberated enough to distribute alternative format content widely @stephenpub #TLC14

— Aki Schilz (@AkiSchilz) June 13, 2014

Gill, asked whether his writers are already experimenting with new forms of narrative, replies: "they're mostly writing".

We bring up one of the issues we've encountered around the Guardian Self-published book of the month: writers spending so much time in self-promotion that they're left with not that much time for writing – and often, the best writers aren't the best marketers, and vice versa. How does a really good writer break through?

Marano says: The best promotion is your writing. "This is, again, about flexibility: what is success? We always think of big numbers, but self-publishing has a big backbone of good writers."

Gill sums this up rather succinctly: “Is it publishing, or privashing?” Is it about publishing and getting your voice heard or about paying mortgages? Traditionally, it's the latter – and that's his job as an agent, he says.

Updated

Diego Marano, of Kobo Writing Life, is speaking:

"What has happened, in one word, is technology". There used to be all kinds of gatekeepers, he says – but now, "as an author – the creator and owner of your copy – you can get in touch with customers". The key word for Marano is flexibilty: "Publishers want to keep doing things the way they've always done them. But that isn't possible any longer. It's not all about paper versus ebook; there are many reading possibilities."

About DRM, he adds: "If you are a young author, the free circulation of your content can be absolutely beneficial for you – every time someone reads your book, you can gain a new fan and potential advocate of you work."

Faber began 1925, Page says: "Faber was a brewer, but his wife hated the smell of beer". It turns out that he was also a poet, and he decided to explore that, creating a community of writers and artists. "Publishers are service businesses, really", he adds. The challenge now, in front of self-publishing, is to make books that people desire as objects.

"The music and the books industry have both been caught in a misunderstanding: that people bought the object for its intrinsic material value. But the object itself doesn't have much value without the reading." Now, you get to make the objects more beautiful, which is something publishers are exploring, he explains. "Publishing in the last 20 years has become all about trade – but that has been broken by the internet."

James Gill, of United Agents, says the last 12 months can be characterised by a "narrowing" of the market, the channels, the types of books, ambitions and expectations. "We have been asked to buy into a narrative of 'big publishing'. The game hasn't changed. Let's get back to basics," he said.

Now over to Stephen Page, CEO of Faber & Faber, who wrote this piece on the subject for the Guardian a couple of years ago.

Updated

Here's a very informative summary from Nielsen

All you need to know about UK eBook sales, in only one slide, thanks to @Nielsen and @TLCUK !! #TLC14 pic.twitter.com/9tDy1AkWn0

— Ricardo Fayet (@RicardoFayet) June 13, 2014

And a couple of interesting factoids from their stats: self-published purchases are rarely planned, and e-books don't have a place in the gift market.

How do readers discover self-published books amid the ever-growing tide of titles? Mainly through browsing online, as well as following previously-read authors.

#TLC14 price & blurb critical for discovery for selfpub books. But fast growing is series. Write for the long term! pic.twitter.com/CxmXJxiDhj

— Joanna Penn (@thecreativepenn) June 13, 2014

Updated

Breaking down the data, print sales fell by 10%, ebooks grew by 20% and purchases of books by self-published authors rose by a significant 79% last year:

Steve Bohme, Nielsen Book: In 2013 sale of printed books fell by 10% but ebooks rose by 20% and self-published books by 79% #TL14

— Claire Armitstead (@carmitstead) June 13, 2014

Here are the numbers for self-published books:

- 18 million books were bought

- 59 million pounds spent

This means roughly one in five ebooks bought last year were self-published. The top genres in all formats are adult fiction. The following breakdown had a lot of members of the audience grinning: romance is in the 7th place overall, it ranks 5th in e-book sales and it's the second most popular genre in self-published books:

#TLC14 spread of genre sales in books incl self published from Nielsen pic.twitter.com/Vu9NvGuPZN

— Joanna Penn (@thecreativepenn) June 13, 2014

Updated

The first numbers are in: 323 million books were bought in the UK in 2013 (for which a total of 2185 million pounds were spent). Overall, consumer sales have remained flat (without counting Fifty Shades of Grey), says Steve Bohme from Nielsen Book.

Audible gasps when Steve Bohme says 323m books bought in UK in 2013 #TLC14. Not a shrinking market then

— Claire Armitstead (@carmitstead) June 13, 2014

UK book consumer sales have remained flat over the last year. Print down by 10%. EBooks up by 20% #TLC14 pic.twitter.com/HcgEDsUzC5

— Ricardo Fayet (@RicardoFayet) June 13, 2014

Updated

Now over to an industry snapshot from Nielsen Book, who will present data on e-books and self-publishing extracted from their survey.

Updated

Doctorow has just finished his keynote – we will post the audio of the full speech later in the day. His talk was full of fascinating insights into the digital publishing industry and advice for writers and artists.

Remember to untick the DRM box when you #selfpublish Most platforms have it defaulted. @doctorow warns indies (My books have no DRM) #TLC14

— Joanna Penn (@thecreativepenn) June 13, 2014

yeaster asked about France cracking down on territorial rights:

Doctorow replies: if territorial rights are visible to readers, you're doing it wrong. "You should never get a message saying: 'You live in the UK, so you can't watch this Stephen Colbert video.' Having unique identifiers for books or videos is not hard. They should never tell you you can't buy a book or see the video, they should direct you to where to buy it." "Until we get it, this will just drive privacy", he ends.

More on censorship and freedom of information:

Doctorow explaining 'ratting': 100 arrested in last month for it - hacking into IDs and exploiting? Mainly sex industry but not only

— Claire Armitstead (@carmitstead) June 13, 2014

Doctorow says that as an artist, he is thankful every day for his ability to make a living from his writing, but "if the choice is between free specch – free from surveilance, censorship, control – and my ability to mke money from telling fairy tales, I'll find a real job." Among laughs from the audience, he insists: "I value a just world for my daughter more than I value my right to tell stories for a living."

Updated

Doctorow's third law is: information doesn't want to be free – but people do.

Doctorow: Information doesn't want anything more from us than we stop anthropomorphising it #TLC14

— Claire Armitstead (@carmitstead) June 13, 2014

Updated

Doctorow is talking about the Amazon-Hachette stand-off and digital rights management.

Doctorow: Hachette could play harder ball by creating their own app for selling books, but they are shackled by DRM

— Claire Armitstead (@carmitstead) June 13, 2014

There are three laws, he says. His first law: if someone puts a lock on something and won't give you a key, it won't be for your benefit.

His second law: fame won't make you rich (as an author), but you'll have a hard time making money if no one has ever heard of you.

Good morning! We're here in sunny London, ready to bring you all the developments from The Literary Consultancy's Writing in a Digital Age conference. Cory Doctorow just started his keynote

So thrilled to finally see @doctorow speak at #tlc14 @TLCUK Talking about the evils of DRM pic.twitter.com/vovVyb7Po5

— Joanna Penn (@thecreativepenn) June 13, 2014

Updated

Welcome to our live coverage of The Literary Conference

Hello everyone, and welcome to the live blog where we will cover the first day of the conference Literary values in the digital age, now in its third year. We will follow the event minute by minute and bring you video and audio content about the future of books. This year's conference, organised by The Literary Consultancy, will be tackling the latest changes in the books trade, with particular focus on the exponential rise of self-publishing and the mixed fortunes of the e-book.

In the meantime, you can:

- Leave your questions in the comment thread below.

- Read Readysteadybook blogger Mark Thwaite on the state of literary blogging in the age of Twitter.

- Check the very informative Storify timeline of last year's conference, centred around quality in a digital age and how to make digital tools and platforms available for authors

• Join the conversation on Twitter using the hashtag #TLC14

The conference kicks off at 9.40am BST with a keynote speech from Boing Boing blogger, science fiction writer and Guardian columnist Cory Doctorow about the issues arising from the new creative moonscape, including those surrounding copyright. Here's a piece he wrote on the subject in 2010. Interesting to see if, and how, his views have changed since that digital prehistory.

We'll be reporting the latest statistics from Nielsen book on self-publishing and e-books in the UK, and quizzing a panel including Faber SEO Stephen Page, leading agent James Gill and Diego Marano, who heads up the self-publishing arm of digital bookseller Kobo, about how much things have changed down on the coalface.

Two years ago, Page issued this clarion call for publishers to be bold, creative and generous towards writers. As a leading light in the Independent Alliance of top UK indie publishers, has he been able to live up to his own ideals?

Join the discussion now, and tell us the questions you think need answering. We'll be reading your questions in real time and will throw them into the discussion.

Updated

A question for the lovely Diego - it seems to me that what is truly revolutionary about writing in the digital age is the exploration of different formats, much of which happens on social sites like tumblr or facilitating sites like New Hive or sharing sites like Scribd. Self-publishing platforms like Kobo, Nook, Smashwords or KDP at the moment do a good job of bringing writers who are wedded to traditional formats to new readers but I'm struggling to see what they are doing to keep up with this new wave of writers taking literature in different directions, so it seems as though they have an interest in wedding themselves to a very traditional notion of what a book is. How do you at Kobo see yourselves tapping into the likes of gifs, memes and interactive e-chapbooks? What are you doing to keep abreast of the way writing itself is changing?