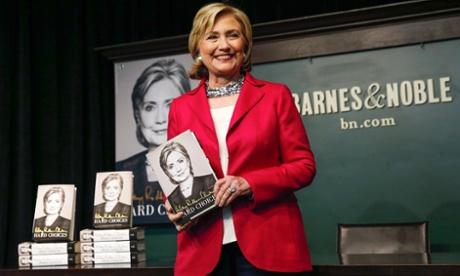

Hillary Clinton launched her memoir, Hard Choices, on Tuesday, laying the foundations for a potential presidential run with a carefully crafted self-portrait of a battle-hardened politician who has bounced back from her bruising defeat in 2008 armed with a clear vision for the future of America.

The former secretary of state, senator and first lady kicked off a typically gruelling nationwide book tour in New York in a blaze of primetime TV coverage. Less of an overt manifesto than The Audacity of Hope, Barack Obama’s book published ahead of his first White House run six years ago, Hard Choices still manages to adroitly position Clinton for a 2016 presidential bid.

The 656-page volume, reported to have earned Clinton an $8m advance, seeks to assuage any remaining liberal doubts over her 2002 vote in favour of the Iraq war, and to bat away conservative attacks over her handling of the Benghazi affair in which the US ambassador Chris Stevens and three other Americans died. It also makes clear that as secretary of state between 2009 and 2013 she spoke her own mind to a president whom she came to respect and like, but with whom she did not always agree.

The book finishes on a tantalizing note. “Will I run for President in 2016? The answer is, I haven’t decided yet.”

'What's your vision for America?'

That ambiguous statement – no surprise from a seasoned politician – belies the fact that Hard Choices is anchored in presidential politics. It begins with her description of her defeat at the hands of Obama in 2008, and ends with a statement of her resolve for America in 2016 and beyond.

She suggests that the question for anyone considering standing for the US presidency should be: “What’s your vision for America?” Then she supplies her own answer: “The challenge is to lead in a way that unites us again and renews the American Dream … Ultimately, what happens in 2016 should be about what kind of future Americans want for themselves and their children – and grandchildren.”

The start of the book is more somber. Clinton admits candidly to having been “disappointed and exhausted” by her failed presidential campaign. “I felt I had let down so many millions of people, especially the women and girls who had invested their dreams in me.”

She is also open about the difficulties faced when, after the 2008 primaries were decided, the time came for Clinton and Obama staff and supporters to try and reconcile. “This was not going to be easy for me … ” she writes. “In fairness, it wasn’t going to be easy for Barack and his supporters either. His campaign was as wary of me and my team as we were of them. There had been hot rhetoric and bruised feelings on both sides.”

The wariness spilled into a first secret meeting between Clinton and Obama shortly after she conceded the Democratic primary race to him. “We stared at each other like two teenagers on an awkward first date, taking a few sips of Chardonnay.”

They cleared the air, but only after Clinton had protested about the “preposterous charge of racism” that had been levelled against her husband Bill during the long and arduous campaign. She also railed against the sexism that she had personally endured, she writes.

But after that sticky start, Clinton says, she and Obama developed a “strong and professional relationship and, over time, forged the personal friendship he had predicted and that I came to value deeply.” By the time of Obama’s re-election for a second term, she talks about the “delight in the partners we had become”.

She describes moments of intimacy between the former bitter rivals, such as an event three days after the 11 September 2012 Benghazi attacks when Obama and Clinton attended a ceremony at Andrews air force base to meet the coffins of the four Americans killed there. “I squeezed his hand. He put his arm around my shoulder … Never had the responsibilities of office felt so heavy.”

But the reader is left in no doubt that Clinton is her own woman, with her own resolute ideas about the nature of American power. She relates how at points of major diplomatic crises she went head-to-head with Obama’s aides – whose youth she underlines archly more than once.

In the days leading up to the fall in February 2011 of President Hosni Mubarak, who she admits had been a personal friend for nearly 20 years, she had wanted to stand by the Egyptian leader but had clashed with the White House. “Like many other young people around the world, some of President Obama’s aides in the White House were swept up in the drama and idealism of the moment.”

When that divergence of opinion became public, Clinton writes that Obama “took me to the woodshed.”

Clinton lost the argument on Mubarak, and Obama eventually called for the Egyptian leader to step down in the face of mass protests. She also lost an argument over Syria, where she had pushed for arms to be sent to the rebels fighting President Bashar al-Assad. “No one likes to lose a debate, including me,” she writes. “But this was the President’s call and I respected his deliberations and decision.”

'Wrong. Plain and simple.'

In her portrayal of her four years at the State Department, Clinton comes across as a faithful servant, but one with her own firm sense of America’s role in the world. Between the lines, she allows herself plenty of wriggle room in which to distance her record from that of the Obama White House, should she need to in 2016.

Hard Choices also gives Clinton the chance to clear skeletons out of her closet. She does so energetically over her vote in favour of President George W Bush’s decision to invade Iraq, her most contentious act as a US senator and one that cost her dearly among committed Democrats during the 2008 presidential primary.

She writes that her hawkish vote had been “wrong. Plain and simple.” Then she tries to turn that confession to her advantage: “In our political culture, saying you made a mistake is often taken as weakness when in fact it can be a sign of strength and growth for people and nations. That’s another lesson I’ve learned.”

A skeleton that is likely to be more difficult to sweep away should she decide to run in 2016 is Benghazi, which Republicans see as a big stick with which to beat her on the campaign trail. She writes about the “crushing blow” of losing the four American officials to the attack on the US compound in Libya, but also lashes out against her conservative detractors.

She doesn’t go quite as far as the “vast right-wing conspiracy” she spoke of at the time of her husband’s impeachment in 1998, but she does lament the “regrettable amount of misinformation, speculation, and flat-out deceit by some in politics and the media”.

She accuses some members of Congress of being “fixated on chasing after conspiracy theories” and others of only showing up at hearings “because of the cameras.” She writes, “They had skipped closed hearings when there wasn’t a chance of being on TV.”

The final section of the book sets out in headlines some of her domestic ambitions for America should she seek the country’s highest office for a second time. “In the end, our strength abroad depends on our resolve and resilience at home,” she says.

Clinton also lists the need to tackle growing poverty and dwindling middle-class incomes, the demand for more good jobs with rising wages and dignity, and investment in a 21st-century economy. She also calls for an “end to the political dysfunction in Washington that holds back our progress and demeans our democracy”.

“It won’t be easy to do that in our current political atmosphere,” she writes, leaving the vivid impression that she’s talking about herself. “Doing what’s hard will continue to make our country great.”