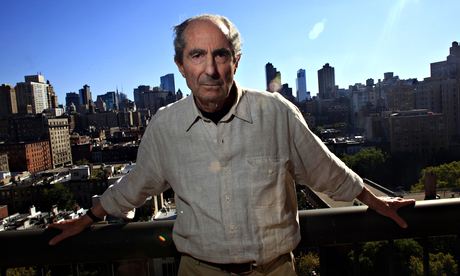

When novelists say they are retiring, experience suggests it's best to nod politely and not believe them. Philip Roth is no exception, although in his case the farewell process – from revealing that he was stopping writing 18 months ago, to this week's "last" interview, with Alan Yentob over two Imagine films, that was also said to be his last public appearance (even if he wins the Nobel?) – has been unusually formal and conducted in stages. Yes, he was very definite about it, but he was also on vigorous form, and we've been here before.

Unless the retirement is due to illness or incapacity – as when it was revealed in 2012 that Gabriel García Márquez had dementia and so had stopped writing – literary novelists tend to be as bad at killing off their careers as writers of detective fiction are at killing off their sleuths. Often what is stated or taken to be giving up writing is in fact giving up publishing. JD Salinger called a halt in 1965, but reportedly left behind five books due for phased release from next year. EM Forster's Maurice was posthumously published, as was a work he adapted into a libretto, Herman Melville's Billy Budd – like Forster, Melville abandoned publishing fiction in the last decades of his life, in his case switching to poetry.

Others, such as Tolstoy – who published no fiction for 20 years, apparently viewing novels as trivial trash from the Christian-fundamentalist perspective of his later years, yet made a comeback with Resurrection – are simply mistaken, failing to anticipate that the itch to write will return. The most spectacular such error was Maeve Binchy's "retirement" in 2000, accompanied by a promise not to do the equivalent of Frank Sinatra's "farewell concerts". Reaction was affectionate when this was followed by five more novels, the first only two years later; as it has been to Stephen King's prolific output over the past decade, notwithstanding his declarations that "I'm done" both before and after the road accident in 2000 that left him with severe injuries.

Similar indulgence greeted Alice Munro's comeback after saying in 2006, "I don't know if I have the energy to do this any more", and the announcement of Anne Tyler's forthcoming A Spool of Blue Thread, although she had said "I want to not ever finish a book again" so that any future offering would have to appear posthumously. Jim Crace, whose plan to retire at around 65 was first voiced five years previously, duly confirmed last year that Harvest was his final novel, but produced an unusual variation on the non-retirement formula by saying that he aimed to pen plays instead.

Devoting yourself full-time to writing resembles retirement, as a substantial book deal typically frees authors from commuting to a 9-to-5 job in a team (IT work for Michel Houellebecq, for example, or TV production for EL James) to toil at home alone, travelling only between bedroom, kitchen and desk. So it's not difficult to see why they struggle with the idea of stopping – how do you retire from your retirement? – or why life after work has become a recurring theme in fiction that might be called Saga sagas.

Among British and Irish Man Booker prizewinners, the protagonists of John Banville's The Sea and Julian Barnes's The Sense of an Ending are retired, while Howard Jacobson's Julian Treslove in The Finkler Question is semi-retired after leaving the BBC. In the US, retirees are at the centre of novels from Jonathan Franzen's The Corrections and Tyler's The Beginner's Goodbye to Richard Powers's recent Orfeo (about an ex-composer and professor) and King's Mr Mercedes, published in June.

Although its hero is a retired cop, the opening scene after a bloody prologue figuratively conjures in characteristically cartoony fashion both the potential misery that would have awaited King if he had really stopped, and the attractions of resuming literary work. Bill Hodges is despairingly watching Jeremy Kyle Show-style daytime TV, with a loaded gun in his mouth, when a letter arrives from the eponymous murderer. He analyses it in detail, makes himself a meal, and realises with surprise that he's singing to himself. Blissfully, his retirement is over.