I'm writing this in Aberdeen library because there's a tight deadline. I've just got off a train and I'm about to catch the overnight ferry to Shetland; there won't be internet access in the North Sea.

I've asked the staff in the reference section to help with figures about the creative industries and I'm writing on a public access computer. If I had a bit more time I'd curl up and read a novel.

Shutting my eyes and reaching out to pick a copy from the shelf. If I hated my choice, it wouldn't matter. Because this brilliant resource, this building full of facts, ideas and images, is available to all of us for free.

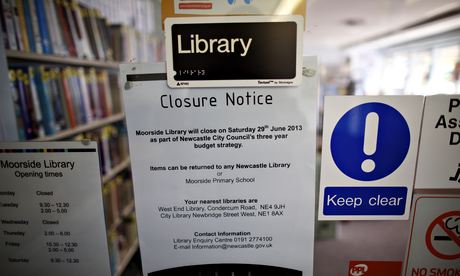

At a time when the Local Government Association has warned that more libraries will be closed and councils struggle with their finances, it's important to think about what we might be losing. Perhaps the problem with libraries is that they are free. We don't value what we don't pay for directly.

Librarians are qualified to degree level, yet we think it's acceptable to replace them with well-meaning volunteers. Much has been spoken about library closures and I've ranted about this too, but now I'm becoming concerned about the de-skilling of our service.

We need the people who run our libraries to understand the potential of books to inspire, inform and change lives. They should have the confidence to display the new and the quirky: books in translation, short fiction, graphic novels. If there's no guaranteed market for these books, they won't be published and we'll all be the poorer.

Of course libraries are worth saving because they nurture imaginations and give us access to the wider world, but there are economic arguments for supporting them too. They are necessary just because council funding is tight and social policy unforgiving. They provide a safe neutral space for people to look for work and they'll be essential when the government enforces online benefit application. In many communities the library is the only place where young people are introduced to any form of artistic activity.

When the creative industries bring £8m an hour into the UK and account for 5.6% of all jobs, surely it's madness to deny access to the ideas that will provide the springboard to creative endeavour. It's a bit like saying: "Hey, of course we want to encourage manufacturing, but it's expensive to teach maths and physics, so let's get volunteers in to do it instead."

This is a matter of equality and democracy. Some people can buy newspapers and magazines, or go online to find the information that will allow them to make an informed choice at election time. Lots don't. Perhaps those people don't use libraries either, but they should have the choice. They should know they exist and the services they provide.

Events such as World Book Night are supported by libraries but seem to be a marketing tool for publishers rather than a celebration of the magnificent system that makes facts and fiction available to us all. Libraries have a poor image. We imagine gloomy shelving, elderly spinsters telling us to be quiet.

Not vibrant places where we can share ideas. Councils certainly won't have funds for powerful ads to change the perception. If a fraction of the budget spent on public health went to raising awareness of what libraries can offer we'd be happier (and probably healthier).

But we can't give up. Are you a library user? If not, then join. Perhaps you can afford to buy books now but that might change. Close your eyes and pull a book from the shelf. Take a chance. If everyone who reads this becomes a library member, borrows books, takes along a friend to a reading group, the government will have to take us seriously. Libraries aren't for the elite or for the deprived. They're for everyone.

Ann Cleeves is a British crime-writer. In 2006 she won the inaugural Duncan Lawrie Dagger for her novel Raven Black.

• Want your say? Email sarah.marsh@theguardian.com to suggest contributions to the network.

Not already a member? Join us now for more comment, analysis and the latest job opportunities in local government.