I've recently returned from New York and I seem, at last, to have resolved my linguistic irritability with Americans, who seem preternaturally compelled to use the word "like" in, like, every sentence. This linguistic tick is largely class, age and gender free. You hear as many "likes" in a Madison Avenue bistro as on a subway train or in the local primary school. It's no wonder that Facebook is always inviting you (not me) to "like" something.

But I seem to have become used to it. I am linguistically very impressionable, and often pick up local accents. This is an entirely unconscious process, and deeply embarrassing. Within a few days of any visit to Texas, for instance, I find my accent twanging, and I start calling folks "Y'all" and men "pardner". In Australia I use "mate"; in New York, "buddy" or "pal". So I was mortified but unsurprised, after my week in Manhattan, to find a number of "likes" insinuating themselves into, like, every 10th sentence. Then, every seventh …

If you can't beat 'em, join 'em. Anyway, being in a state of constant linguistic dudgeon is bad for the digestion. So I no longer wince when I hear the ubiquitous "likes", though my fantasy of being a schoolteacher and forbidding the word in class abides. The result, I suspect, would be a classroom struck dumb by their incapacity to frame a like-free sentence. Imagine the frustration and indignation. "We're, like, on strike!"

I am mellowing linguistically, no doubt about it. I used to cringe when I saw the term "login", and positively squealed when I first heard "snail mail." But our new e-world seems to generate as many new words as programmes and gadgets, and you have to learn them, give in, and shut up.

No, there is only one relatively new term that – though it has come into common usage in my professional world – continues to drive me absolutely crazy, and that is "flat signed." Pause. For those of you who know nothing of the world of rare books, what does such a term suggest to you? Not a lot, I presume. Hard even to know how to guess.

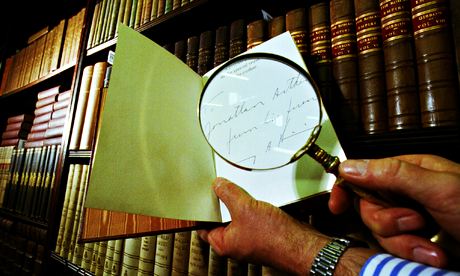

I first heard the term sometime in the 90s, I believe, when some American dealer – was he from Texas? – began to advertise books from his stock that were "flat signed" by their author. By which he meant "signed". As in: merely signed. It is of course necessary to make distinctions about the ways in which an author's pen can impose itself on a book. He can give it to a friend, in which case it is a presentation copy, and if that friend is as famous as he is, or perhaps a relative, you call the result an "association" copy. If, on the other hand, the presentation is to a relative stranger, and obtained under a degree of polite duress, we usually call that an "inscribed" book.

TS Eliot, when asked by a stranger to sign a book, wrote "Inscribed for J Fred Muggs" (or whoever) "by TS Eliot," which meant "I do not know this person and have certainly not given him my book." This is slightly frosty. The worst example I ever came across was in the late Alan Ross's library, in which he had several volumes inscribed for (not to) him by Anthony Powell: "Alan Ross is hereby confirmed in possession of this book". Ouch. And Ross, unembarrassed by this froideur, counted Powell amongst his friends.

These categories are fluid, and neither is to be confused with those instances where an author merely signs his or her name, usually on the title-page. Often publishers send out hundreds of these ready signed books, which the author will have done in their editor's office, supported by a junior member of staff, who holds open the page, and intravenously administers stimulants. At book fairs, too, many authors merely sign their books, though most are congenial enough to offer an inscription if they can be informed to whom.

But in the last couple of years I have noticed, in signing my books at literary festivals, that more and more people just want a signature. Not an inscription to personalise the book. No added date, or place. Just a signature, thanks. Flat signed. I have become a flat signer.

My rare book business is unusual in a number of ways. I carry hardly any inventory, and am uninterested in books that are merely first editions, even if they are in superlative condition, mint dustwrapper and all. No, what I like is association copies: books that carry a narrative punch. Looking round my shelves at the moment, I see books inscribed by DH Lawrence to Mabel Dodge Luhan; James Joyce to Jonathan Cape; Virginia Woolf to Clive Bell; Evelyn Waugh to Dorothy Lygon; Angela Carter and Ian McEwan to Malcom Bradbury. It goes on and on. Each book requires an explanation, which I am always happy to provide. When I encounter a book that is merely signed, I feel a trifle disappointed. When was it signed, I wonder, and why, and for whom? A simple signature feels bare, a bit mean, withheld.

So what are we to make of this new generation of collectors, who prefer it that way? The answer is not entirely stupid. First, there is some resistance to books inscribed – "For Fred, from Graham Greene" – where no-one knows who Fred is, or was. This is not entirely satisfying. Perhaps a simple signature is preferable? And if you collect only books with simple signatures (note: I still cannot get myself to call them flat signed) there is a certain uniformity – look, all of them just signed! – that is pleasing to the eye of a certain type of (boring? sterile?) collector.

Oops. I have several customers, of whom I am fond, who insist on flat signed books, and though I like teasing them, I am not really as contemptuous as I sound. I guess what you could call me is, like, old fashioned.