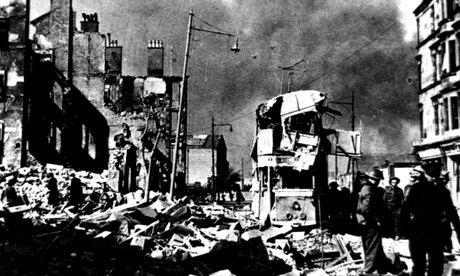

During the heaviest night of bombing London endured in the blitz, in May 1941, the novelist Rose Macaulay's house was bombed. She lost everything apart from the clothes she was wearing. If you are a writer, one of the worst things you can lose is your book collection, and Macaulay had a particularly impressive one; even the destruction of her own novel in progress did not depress her as much. She even mourned the loss of her Baedekers, which I had always presumed were the stuff of highbrow scorn (see TS Eliot's "Burbank With a Baedeker; Bleistein With a Cigar"); these were now irreplaceable. But: "anyhow, travel is over, like one's books and the rest of civilisation," she said in a piece, "Losing One's Books", she later wrote for the Spectator.

That civilisation was killing itself was not an unreasonable or extravagant way of looking at the second world war and its runup; and in such circumstances people can do strange, reckless things. Not long before, and a few months after the loss of her London apartment and the Hogarth Press within it, Virginia Woolf had walked into a river with her pockets filled with stones. (Feigel does not commit the post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy, but you can't help feeling that having her home flattened didn't exactly cheer Woolf up.)

So it was a good idea of Feigel's to look at the war as it appeared to Londoners through the eyes of novelists. She has picked five: Elizabeth Bowen, Graham Greene, Henry Yorke (who published as Henry Green – a first-rate novelist, now not very widely read), Macaulay, and Hilde Spiel.

Who she? Spiel was an Austrian novelist who had managed to escape to England before the war. Well known in her native land, she's largely unknown in the UK, and at first I wondered why Feigel had brought her into this story when there were so many other contenders (Evelyn Waugh, George Orwell, Nancy Mitford). Then I realised it was quite clever: it widens the scope and gives us a purchase on what it was to be an outsider in such circumstances (her isolation in this country is as great today as it ever was, so to speak).

One notable thing people did in those times was indulge appetites that until then had had to be suppressed. Greene, who had felt half-dead before the war, came alive during the blitz. It was from him that Feigel got her title: "The nightly routine of sirens, barrage, the probing raider, the unmistakable engine (Where are you? Where are you? Where are you?), the bomb-bursts moving nearer and then moving away, hold one like a love-charm."

For Yorke, this proved to be literally the case. Women going out for the evening on a date would ask each other if the man was worth dying with; and it would appear that many of them considered Yorke worth the risk. He would cable his wife regularly telling her, in the capitals of telegramese, not under any circumstances to come to London; one thinks no less of him as a writer, but a bit less of him as a man. As for Bowen, she didn't like her lover Seán Ó Faoláin's cracks about the English and the war (he was a former IRA man, after all), and took another eventually; and Macaulay was already devastated at the agonisingly protracted death of her lover, injured in a car accident for which she, a typically reckless driver, was to blame.

This is all very entertaining, although it has to be said that for all the seriousness of tone, what we are dealing with is basically the Higher Gossip, in which diligent fossicking around the private lives of writers is justified in consideration of the insight it gives into their work. (It is, alas.) But why the book follows these writers around for so long after the war is a little mystifying. I suppose it is simply to illustrate that, even after the horrors of war, life went on – in the composition of all the books that the war had inspired them to write.