Last week the celebrated controversialist and novelist Hanif Kureshi said that creative writing courses are a "waste of time". It's encouraging to see that, now he's a professor of creative writing, his views are becoming more positive: in 2008 he declared creative writing courses "the new mental hospitals". It's also reassuring to see him maintaining the old tradition of professors biting the hand that feeds them.

Kureshi's (repeated) remarks come at a time of huge growth in creative writing degrees. According to figures from the Higher Education Statistics Agency (Hesa), there are 4,260 full time undergraduates studying imaginative writing, a figure which doesn't include students taking joint honours, or creative writing elements within English. There's a subject body, the National Association of Writers in Education (Nawe), which produces a superb website and magazine, and has over 500 members.

The qualifications provider AQA introduced an A-level in creative writing this year. Even more significantly, although deep in the infrastructure of educational reform, the Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) is developing a benchmarking statement for creative writing, separate from any parent discipline.

Creative writing as a discipline is misunderstood

Kureshi, who doesn't regularly teach any undergraduates at Kingston, and others who echo his comments dismissing the (mythical) students who expect to win the Booker prize, miss the point of the subject. They fail to see what creative writing in higher education manifestly is: not a short cut to publishing millions but a demanding academic discipline closely bonded with the study of literature.

The disciplines of creative writing and English have always had a complex relationship. Some commentators see them as rivals (when Nabokov was offered a chair at Harvard, one linguist asked: "What next? Shall we appoint elephants to teach zoology?") or more damagingly, as parent and child. Both these views are wrong. Gerald Graff's definitive history of English in the US stresses precisely how an influx of poets and creative writers to universities in the 40s and 50s refreshed and regenerated two generations of students and academics.

Something similar is happening now in the UK. Just as the influx of ideas and methodologies from philosophy and politics shaped university English in the 70s and 80s, and a focus on history changed the subject in the 90s, now the huge growth of creative writing is changing English – and creative writing as a discipline - in unpredictable and fascinating ways.

Learning by doing

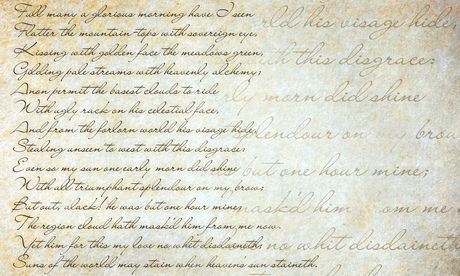

English as a subject is learning new ways of approaching and responding to literature. Although all reading and criticism is properly creative, English is relearning the uses of learning about texts by doing: the best way to find out how a sonnet works is to write one, and to have conversations about what writing a sonnet means, for a writer, for a reader, and for a society. This isn't to ignore the gender politics of, say, Shakespeare's sonnets, or to pass over their historical context, but it is to focus also on the nuts and bolts of how writing is done, and why that process matters.

Creative work also learns from literary study. David Mitchell's tricksy bestseller (and Hollywood film) Cloud Atlas self-consciously mocks itself in the voice of one its narrators as the sort of writing that's informed by "MAs in postmodernism and chaos theory". Many of the novelists on the 2013 Granta 20 under 40 list are creative writing and English graduates, and teachers. And – far from Hollywood - POLYply, the cult monthly experimental art event combining poetry, film, music, and performance, engages with a unique combination of ideas from literary theory and art, and is the brainchild of university-based creative thinkers and writers.

Both English and creative writing are simply disciplines, as are history, biology, sociology and so on. A discipline provides a rigorous framework for investigating the world, and an individual's relationship to the world. Each discipline does this in its own ways. Creative writing does it by finding and developing literary and artistic forms for combining imagination, knowledge, and language. Like other disciplines, it cannot find its meanings only through itself; creative study is an intrinsic partner of not only English, but many other disciplines as well.

Those teachers and students who wish to view creative writing merely as a playground for future prizewinners and bestsellers do so at their peril, and really are wasting their time.

Douglas Cowie is an American novelist and senior lecturer in creative writing at Royal Holloway, University of London – follow him on Twitter @DouglasCowie.

Robert Eaglestone is professor of contemporary literature and thought at Royal Holloway, University of London – follow him on Twitter @BobEaglestone.

This content is brought to you by Guardian Professional. Looking for your next university role? Browse Guardian jobs for hundreds of the latest academic, administrative and research posts.