In the uneasily internationalist world of the post-Stalinist Soviet Union, borders were closed, yet also permeable. Growing numbers of Soviet citizens began visiting the west, not just on business, but on tourist packages: people now in their 80s and 90s recall these visits as revelatory. In the other direction went thousands of foreign tourists – providing essential injections of hard currency – students and academic specialists. The "scientific exchanges" students and scholars took part in were important instruments of cultural diplomacy and of international intellectual dialogue, shaped by top-level negotiations between the USSR and western powers.

The presence of this secondary category of foreigners in the USSR was at once a source of pride (they have come to learn from us) and of anxiety. "Foreign spy centres carrying out subversive work against the Soviet Union exploit the system of international scientific exchanges in order to engage in ideological diversion," fulminated a pamphlet published in Leningrad in 1970.

It turned out that anything from lending your Russian roommate a copy of the Reader's Digest to having an inadequate grasp of your chosen topic of research could be seen, in a certain light, as "diversionary". The visiting westerners, particularly students, were subject not just to the control of the Soviet authorities, but to micro-regulation by the western government agencies that organised their visits, and which were eager to avoid "international incidents". The appearance of the Leningrad pamphlet generated a long, anxious article in the Times.

Sheila Fitzpatrick's absorbing memoir is set in this John le Carré era of accusation and counteraccusation – what we now know to be the last convulsions of the cold war. Some of what she describes will be familiar to anyone who spent a year or two as a student in Russia back then. The "honey trap" operations that were supposed to besmirch the visitors as sexually deviant, the intrusive interest about one's affairs from neighbours in the hostel (as a Russian friend of mine put it, "you don't end up living there if you're a normal person"), but also the extraordinarily close and sudden friendships with chance acquaintances whom you might never see again after you left. And all hectically overlit by the fear of becoming Exhibit X in one of those denunciatory pamphlets (in the city where I spent the academic year 1980-81, the local masterwork had the resonant, if anachronistic, title, The Cheka Officers of Voronezh Tell All).

As a historian working on the Soviet period itself, though, Fitzpatrick was in a different position from most of us. She was determined from the beginning to become an accurate observer of Soviet life (it was much more typical to escape this by studying pre-revolutionary Russian culture and sticking to the company of the many younger Russians who were mainly interested in that, along with such western imports as jeans and whisky). Fitzpatrick came equipped, as her title suggests, with the fledgling professional historian's commitment to work in the archives (a bold and even risky step back then), and she was far-sighted enough to keep a detailed diary of her experiences. All this has allowed her to write an exceptionally lucid and purposive account of her experiences.

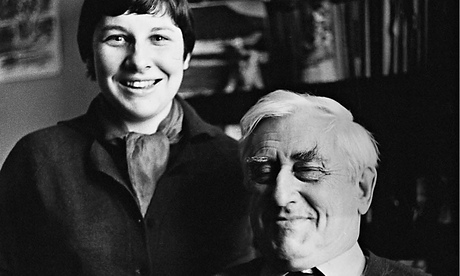

Certainly, there are some splendid stories, such as a bungled seduction by an east German posing as an expert on Fitzpatrick's research topic (the Commissar of Enlightenment and Old Bolshevik, Anatoly Lunacharsky); or the tale of how the "right" way to achieve what she wanted in the state archive of the October revolution turned out not to be reasoned argument, or even conspicuous hard work, but strategic floods of tears. Yet this is not in any sense an "anecdotal" book. Instead, it pursues three distinct narrative lines: Fitzpatrick traces the vicissitudes of obtaining documentary material to support her studies, in the face of constant bilking and censorship; she describes the emotional ups and downs of life in the enclosed student community of Moscow State University's wedding-cake hostel; and, most memorably, she depicts her close friendship with a Lunacharsky connection, Igor Sats, who also became her entree to the most dynamic and important literary journal of the 1960s, Novy Mir.

Fitzpatrick had the extraordinary – and among foreigners, surely unique – experience of reading Novy Mir's literary sensations while they were in production, including Solzhenitsyn's novel Cancer Ward (which in the event was banned in 1968, and came out in Russia only in 1991). This did not stop her from taking a cool view of the text's merits, and in particular, its unconvincing representation of the two leading female characters. Independence of aesthetic judgment is a point that Fitzpatrick underlines, also noting that she found the much-admired performances of Monteverdi by Andrei Volkonsky's Madrigal group kitschy in their semi-staged, histrionic emotionalism.

The portrayal of Moscow conclusively undermines any sense that the "official art" of the late 1960s and early 1970s might have been a unified or unadventurous phenomenon. And the city was the Soviet capital of oppositional political currents, broadly conceived, as well as the seat of government.

First visiting the USSR as a graduate student at Oxford, Fitzpatrick found (like many of us) the re-entry into British culture if anything more dislocating than arrival in Russia. The university seemed provincial compared with Moscow, its Soviet specialists ill‑informed and intellectually limited. On a short trip back in the spring of 1968, she discovered that "for Novy Mir, the political weather was blustery and uncertain", and the city a sea of mud, but that the events in Prague gave every cause for optimism. The Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia a few months later prompted searing disillusion, and in the same summer of 1968, she was denounced as a tool of anti-Soviet propagandists in the Sovetskaya Rossiya newspaper. The effect was to make still more painful the ambivalence Fitzpatrick already felt as the daughter of a civil liberties activist and economic historian, and who was unwaveringly committed to the left, but never part of the communist establishment.

In the event, her solution to the dilemma was to arrange another extended trip to Moscow as quickly as she could. The further exposure to research resources on the spot, and the imaginative manner in which she worked round the restrictions on the material she was shown, laid the foundations of a stellar career as a historian. But unlike some academic autobiographers (Eric Hobsbawm, for instance), she does not focus on the progress to renown of a prominent scholar. Instead, this is a book about self-discovery, and about the shy, self-doubting but unusually astute and determined young woman who embarked on it. Both an institutional outsider (as an Australian living in Britain and the US), and an outsider by temperament, she has a gift for grasping what others usually miss. As a result, A Spy in the Archives is a remarkable record not only of personal history, but of Soviet and indeed British history as well.

• Catriona Kelly is the author of Children's World: Growing Up in Russia, 1890-1991.