Four years ago, when it came to the publication of my first novel, my publisher asked me for the names of authors I admired. The idea was to send these authors a proof of my book in the hope that they might provide us with an obliging quote to use on the cover.

My list was brief. At the top of it was Elizabeth Jane Howard, a writer I had come to relatively late in life. For years, I had stupidly dismissed her books because of their rather twee jacket covers featuring blotches of paint and bucolic countryside scenes. It was only when a colleague insisted I try the Cazalet Chronicles that I saw how wrong I had been.

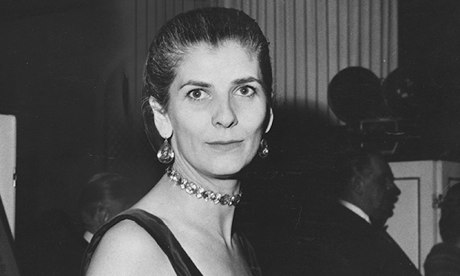

Elizabeth Jane Howard rapidly became one of my all-time literary heroes. She had lived a fascinating life – married to Kingsley Amis, stepmother to the more famous Martin, affairs with Cecil Day-Lewis, Laurie Lee and Arthur Koestler – but it wasn't this that won me over.

It was the way she wrote: fluently interlacing different viewpoints without moral judgment and never once losing the tightness of the narrative structure. Several times during the drafting of my first novel, I returned to Howard's prose to see how she had crafted a passage of technical difficulty.

So when my publishers forwarded me a neatly typed letter on A5 headed notepaper from Howard herself, I was thrilled. She had read my book and said some nice things about it, before pointing out a minor error. I'd included a sweating dog in one scene: "Dogs cannot sweat anywhere but their tongues," she wrote confidently. She was right, of course.

When Howard turned 90 last year, I pitched the idea of an interview to my editor. I had long felt Howard was due for a re-evaluation, and The Cazalets were in the process of being dramatised for Radio 4. She had also just delivered the final instalment of her wonderful postwar saga to her publishers.

I turned up at her house in Bungay, Suffolk on a grey day in April. In person, Howard was as acute and brilliant as she is on the page, albeit disbelieving that anyone would think her writing was any good. When I told her I felt her work was finally being given its due, she responded with a startled glare. "Gosh, I'm feeling really inflated today, watch out. My head is swollen and empty."

She smoked, drank (much-hated) decaffeinated coffee and barked with laughter. She had an amazing mind, but was in no way grandiose, confessing at one point to a liking for the first series of I'm a Celebrity… Get Me Out of Here! because she was so fascinated by people.

I saw her again last November, when I was lucky enough to sit next to her at a lunch to mark the launch of her new novel, All Change. She looked beautiful, as ever, wearing a golden cameo necklace containing a lock of Mozart's hair, and although our conversation ranged broadly, she kept coming back to how everyone else at the table was feeling. She would lean in and ask me softly if so-and-so was alright as "she's had a hard time of it". At 90, she was still fascinated by people and cared deeply about what was going on in their lives.

That was two months before she died. I had to leave early to catch a train. I wish I'd stayed longer.