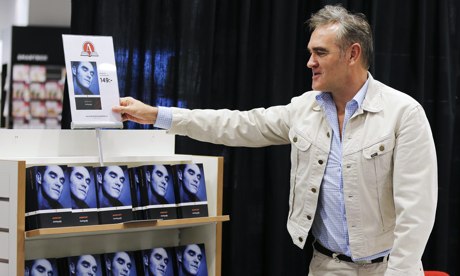

Thanks to a hyped-up fuss that has done its job in spades, this much we all know: owing to its author's provocative cheek and his publisher's marketing nous, Morrissey's autobiography is a Penguin Classic, which means it shares its imprint with Ovid, Plato and good old Thomas Hobbes. Self-evidently, though, it's also a high-end example of a literary genre that now seems to form at least half of the publishing industry's raison d'etre: the celebrity memoir, 2013's most notable examples of which include the self-authored life stories of Mo Farah, Jennifer Saunders, Harry Redknapp and Katie Price (again).

Despite career wobble after career wobble, the author has become an unlikely British institution: as the blurb on the back reminds us, "in 2006, Morrissey was voted the second greatest living British icon by viewers of the BBC, losing out to Sir David Attenborough". As unthinkable as it still seems, the prime minister will presumably be chillaxing with a copy as soon as he gets the chance.

What awaits him is, in its own way, as faithful to the celeb genre as all the other books that are piled into branches of WH Smith at this time of year. Though its 457-page splurge of text occasionally suggests a bold stylistic experiment – there are no chapters; nor, for the first 10 pages, any paragraph breaks – as with so many famous-person books, it also betrays a lack of editing. So too do some very un-Morrissey-like American spellings ("glamor", "center" – this is in the UK edition), his strange habit of jumping between tenses, and the odd passage that simply doesn't make sense. "I will never be lacking if the clash of sounds collide, with refinement and logic bursting from a cone of manful blast," he writes on page 90. You what?

And yet, and yet. For its first 150 pages, Autobiography comes close to being a triumph. "Naturally my birth almost kills my mother, for my head is too big," he writes, and off we go – into the Irish diaspora in the inner-city Manchester of the 1960s, where packs of boys playfully stone rats to death, and "no one we know is on the electoral roll". In some of the writing, you can almost taste his environment: "Nannie bricks together the traditional Christmas for all to gather and disagree … Rita now works at Seventh Avenue in Piccadilly and buys expensive Planters cashew nuts. Mary works at a Granada showroom, but is ready to leave it all behind." And when pop music enters the story, he excels. Before the Smiths, Morrissey fleetingly wrote reviews for the long-lost music weekly Record Mirror under the name Sheridan Whiteside, and his talent for music writing is obvious. By the late 60s, he is marvelling at hit singles by the Love Affair, the Foundations and the Small Faces; in 1972, as with so many thousands, he marvels at David Bowie miming to Starman on an ITV pop show called Lift Off With Ayshea. "It seemed to me that it was only in British pop music that almost anything could happen," he writes, which is spot on.

School, unsurprisingly, is hell, complete with Catholic guilt, unending brutality, and one grim incident in which a PE teacher molests him. When he leaves St Mary's secondary modern, he falls into a period of torpor and self-doubt. And then Johnny Marr pays him a visit, and his life takes off – while, in keeping with an unwritten rule of celebrity memoir, Autobiography takes a serious turn for the worse.

There are not many more than 70 pages on the actual experience of being in the Smiths, and around a quarter of those are devoted to complaints about their record label, the supposed commercial underperformance of their singles, and Geoff Travis, who founded Rough Trade records in the mid 1970s, and has clearly not been on Morrissey's Christmas-card list for several years. At first, what Morrissey says about Travis and his colleagues can be waspishly funny: before they signed the Smiths, he reckons, Rough Trade's brand was "tubercular … hand-crafted on a spinning jenny". But after pages and pages of moaning, it all starts to pall. Moreover, a pattern is set: any calamity or mishap is always someone else's fault.

As the story winds on, the clash between this account and the story as told by Marr and others becomes violent: as all other credible accounts have told it, the Smiths broke up because Morrissey would not be handled by a manager, and as their business dealings turned chaotic, Marr was worn down by not just playing the guitar and writing songs, but dealing with lawyers and booking hire-vans. Small wonder that the two of them "signed virtually anything without looking", or that their bond came to grief, probably the single biggest event in Morrissey's adult life. In the absence of even the barest recognition of any of this beyond a tortuous passage that claims that all managers "merely manage their own position in relation to the artist", Autobiography presents the end of the Smiths as a mystery, sullied by some innuendous stuff about Marr supposedly growing envious of Morrissey's profile, which does not stand up to any serious scrutiny.

"Beware, I bear more grudges/Than lonely high court judges," went the lyric of Morrissey's 1995 single The More You Ignore Me, the Closer I Get, and he wasn't lying. As the bitterness overflows, there are still flashes of wit, along with some rather rum views (his opinion of the Kray Twins might strike some as charitable). Circa 1994, he finally finds love and companionship with one Jake Walters, who has "lived a colourful 29 years as no stranger to fearlessness" and who has "BATTTERSEA" tattooed inside his lower lip. Morrissey evidently melts – but soon after, he reaches his peak of bitterness and unrestrained verbosity: 40 pages on the court case in which Smiths drummer Mike Joyce ("an adult impersonating a child", he reckons) successfully made a bid for 25% of the band's posthumous earnings, and a judge named John Weeks apparently became the human being Morrissey hates most of all. Here, all levity evaporates: it's understandable that he feels so aggrieved, but when the verbiage dedicated to this stuff threatens to eclipse what he has to say about every other aspect of his career, something has gone badly wrong.

Towards the end, things pick up: he enjoys a career renaissance, moves to Rome, and once again finds romance and companionship with a character he calls Gelato. But a sour taste remains, and it's hard not reach for a line from that beautiful Smiths song Half A Person, released a quarter-century ago: "In the days when you were hopelessly poor, I just liked you more."