As someone who measures out their life in press releases and the occasional murmur of litigation, Morrissey has become more of a celebrity than a musician. Yes, he sometimes releases albums and still has rabid fans, but the maintenance of It – the fame, the public persona – has taken up his energy for quite a while. His autobiography will be seen as part of that maintenance – which on one level, of course it is – but that is to do him a disservice. For, before all the bickering and bitterness, there was something magical and extraordinary.

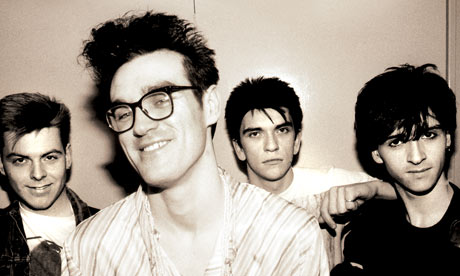

Well, as Jimmy Castor once stated: "What we're gonna do right here is go back: way back, back into time." Thirty years ago, the Smiths were a young group, in the first intense flush of energy and creativity. During 1983, they released two classic singles – Hand in Glove and This Charming Man – and recorded another, What Difference Does It Make? They also recorded four BBC sessions and two different versions of their first album – one with Troy Tate (still unreleased, bar a handful of songs) and the other with John Porter.

Hand in Glove is a total rush, an ecstatic release of pressure and a deadly declaration of intent. Almost all of the Smiths' output during that year shares that heady sense of freedom, expressed in an outpouring of songs that mix desperation, compression – all those ideas dammed up and then unlocked – and sharp observation. Morrissey's unique lyrical and vocal approach was more than matched by Johnny Marr's melodies and arrangements: these gave structure and appeal to the complex emotions that always threatened to burst through the song's structure.

Morrissey's biography is well-known. In early-80s Manchester he seemed destined for something, but what that was nobody quite knew. He seemed destined to stay on the outside, his abilities unrecognised. His appearance as the frontman for such a powerful group was an extraordinary act of self-reinvention that has carried him through the rest of his life. The sheer glee of this transformation can be heard all the way through the Smiths' first year, as joy and relief mix with revenge and, most crucially for his growing audience, pathos and empathy.

1983 was not a great year for rock music. The synthpop wave of the early 80s had almost run its course. Electro and hip-hop were making great strides, but for those who liked guitar groups, the pickings were slim: Porcupine by Echo and the Bunnymen, REM's Murmur. At that period, rock music was still seen as a method of generational identification – the place where the preoccupations of teens and twentysomethings could be expressed – and as a flag to which the outsider could rally. The only problem was that in 1983, there wasn't much of it.

Morrissey had been an outsider, and he carried both the insights and burning resentments of this state into his art. Almost all the early Smiths songs concern rejection, friendships sundered, frustrated sexuality, and the transience of human connection. Although to some extent challenged at that point by Ian McCulloch and Michael Stipe, the standard persona of the rock singer in the early 80s was still about power and control, if not machismo: in contrast, Morrissey sang about failure, hurt, illness and hopelessness.

That had great power in 1983. The pop lie of the time was the sense, propagated whether intentionally or not by Wham! and Duran Duran, that all young people were contentedly living the dream of shiny consumerism. As Stan Campbell of the Special AKA sang in that wonderful single, Bright Lights – one of the only other songs to comment on this metropolitan mode: "I thought I might move down to London town/ I could get in a band, have fun all the year round/ The living down there must be pretty easy/ I could rip up my jeans deliberately."

As today, young people were at the sharp end of a Conservative government's policies. Outside the south-east, unemployment was high. The Smiths were defiantly rooted in Manchester, and not even the fashionable sites of the Haçienda and Factory Records: their territory was disused railway lines, a rented room in Whalley Range, the bleak moors that still hold their awful secrets. Suffer Little Children tackled the Moors Murders head on, that dreadful stain on the city's history: "Oh, Manchester, so much to answer for."

The Smiths aimed to tell a particular truth, about lives ignored by the mainstream media and about a grim, north-western landscape that helped to create a bleak, vengeful emotional state. Morrissey wrote about poverty in Jeane, the Smiths' most affecting (and underrated) song from this period: "There's ice on the sink where we bathe/ So how can you call this a home/ When you know it's a grave?" This was the world of Shelagh Delaney's A Taste of Honey: the kitchen-sink desperation of the early 60s revisited 20 years on. The implication: very little has changed.

In 1983, the Smiths were an extremely powerful package: a total artwork of music, lyrics, clothes, graphics, attitude and worldview. This was the return of the repressed, and they quickly found a youthful audience that stayed with them as they grew in leaps and bounds. For the next three and a half years, they continued to produce a constant stream of songs that have become one of the iconic 80s catalogues. All the plaudits – while they may be hard to understand for the unconvinced – are totally deserved.

If it is Morrissey's tragedy – as it is the tragedy of pop music as youth culture – that he appears stuck in his youthful persona, then that should be balanced against his youthful courage and his considerable achievements. But an autobiography is a book of a life. In Morrissey's case, which life are you going to get: the joyous, barbed but humorous spirit of the Smiths' years, or the inward-looking, self-obsessed curmudgeon of his middle age? The jury's out, but I know which one I would like to read.