Portraiture is a strange and impure art. It includes many of the most profound masterpieces of painting and sculpture. Rembrandt's self-portraits, Bernini's bust of Costanza Bonarelli, Velázquez's Pope Innocent X – at its most elevated, the portrait can be an intense analysis of the human condition.

But at the same time, a portrait is a record of a particular person – and however much art critics may bang on about the meanings of portraits, many people simply want to see someone honoured by art.

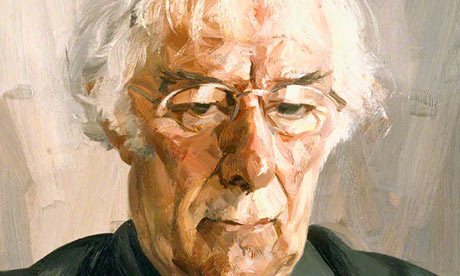

Me too, when it's someone I revere. That's why I am really pleased the National Portrait Gallery has just hung a portrait of Seamus Heaney.

Tai-Shan Schierenberg's portrait is – as far as I know – the first such official commemoration for Heaney on a British stage. I thought it a poor show that no major figure from the British government attended his funeral, given his eloquent anticipation of the peace process in poems that enact reconciliation in language.

Heaney was a war poet who wrote about a war on British soil. Memory was at the heart of that war, and elegy one of his great gifts. Grief seeps out of the peat in his great collections North and Field Work. It was strange to read in some appreciations that his was a soft, rustic voice. Too many readers seem to have stopped at his early poem Digging.

Violence cuts across Heaney's pastoral passions and makes him speak out as a citizen. Like the first world war poets, who were torn from a rural Edwardian bliss to the fields of hell, Heaney's destiny was to find a voice that could rise to the horrors and losses of the Troubles.

In North, he finds analogies for his time in sacrificial victims preserved in bogs and Vikings buried with their swords. In Field Work, he translates Dante's story of the revenge of Ugolino, who could not forgive his persecutor and so has to chew on his head forever in the depths of the Inferno. Heaney's poetry is eternally relevant, and speaks of every conflict, especially civil conflict. His elegies for friends killed in the Troubles are timeless poems of loss.

In Wales for the funerals of my parents last winter, it was Heaney I kept reading, again and again.

A statue in central London should be raised to the poet, who revealed the inner goodness of our language. Meanwhile, the National Portrait Gallery has done right to hang the portrait of this truly great man.

• This article was amended on 17 September 2013. In the original subheading, the poet was described as British.