If you haven't read Colm Tóibín's The Testament of Mary, you may know it as the short one on the Booker shortlist (and therefore not a bad place to start). It has only 104 pages. But what makes it really striking – in addition to its compelling narrator, lyrical physical evocation of its time and place and bombshell ending – is the fact that it is another novel about Jesus.

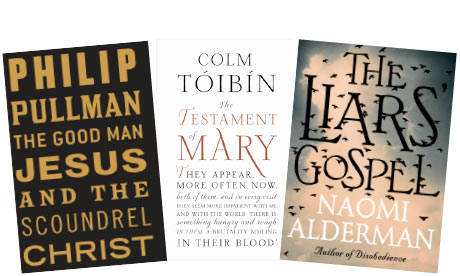

Jesus is having a moment in literary fiction. Novelists can't get enough of him. In September 2012, Naomi Alderman's The Liars' Gospel was published – a month before Tóibín's book. The year before that came Richard Beard's Lazarus is Dead, and before that Philip Pullman's The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ. More allegorically, JM Coetzee's Childhood of Jesus appeared earlier this year.

"There have definitely been more novels about Jesus recently," says Stuart Kelly, who is on the judging panel for this year's Booker. He thinks they might be a reaction to the current situation in the Middle East, or "the gauche and strident atheism of the likes of [Richard] Dawkins. People can argue what they like about the new atheism, but what it doesn't do is explain why this story has had such a hold over the human imagination for 2,000 years."

So why has it? Rowan Williams, the former archbishop of Canterbury, has read the novels by Pullman, Jim Crace (whose 1997 book Quarantine is about Jesus's 40 days in the desert) and some of the Coetzee. He thinks the story in the gospels intrigues novelists because: "It is a story freighted with the most immense irony imaginable – the decisive embodiment of divine action and purpose and power in the human world turns out to be not only a wandering peasant shaman, but a figure who fails to persuade and ends up humiliated and executed."

"Decisive" these portraits are not, however. Tóibín's Mary is determined not to oblige the gospel-writers seeking to preserve the teachings of her son (she can't bring herself to say his name). They seem more interested in the story than in the truth, and Mary's son comes across as an annoying figure with a loud voice and weird clothes who takes up too much pavement space – a sort of first-century hipster. Alderman's Miryam differs by obliging a follower by telling him what he wants to hear about her pregnancy. "She knows that the story she is telling is a lie, but she says it anyway … because it brings her comfort to see that he believes it."

As that last sentence suggests, the writing of the gospels is woven into the plot of both Alderman's and Tóibín's books. Perhaps the story of Jesus's life bears novelistic reiteration partly because it has always been told by multiple voices – not only Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, but many more whose versions were not included in the Bible.

That duplication and overlapping of narratives must create holes and folds in which novelists can work, to narrativise the contradictions and build new worlds in the gaps. After all, each telling carries its own truths, and the collective effect of their variation is to suggest there is no such thing as a gospel truth – just lots of gospel stories.