I read Jack Kerouac's On the Road for the first time on the way to the bull-running at Pamplona in 1991, on a rattling 24-hour bus ride from London. I missed most of France, my nose buried in the paperback – captivated, as all 21-year-olds should be, by Kerouac's bebop prose, his freedom and spontaneity. That paperback survived San Fermin somehow and, when I got home, I started pursuing the other Kerouac novels it listed.

Because that's what I thought they were: novels, fictions. But by the time I'd found The Dharma Bums and Big Sur, I had an inkling that these apparently unconnected novels were nothing of the sort. It wasn't until a few years later, standing one blazing July afternoon at his grave in his Massachusetts hometown of Lowell, that I began to appreciate the scope of what Kerouac intended: a roman fleuve, a memoir cycle woven into the mythic, wondrous tapestry of his life.

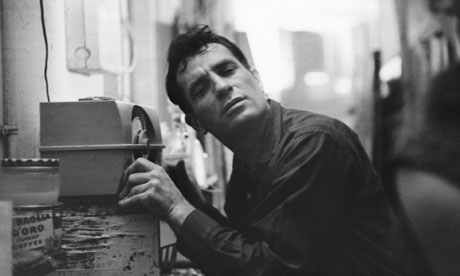

It seemed natural to assume that the Kerouac books published after On the Road were written after it became a bestseller in 1957. But many were written well before, as part of a huge history Kerouac had first envisaged 14 years earlier, when he was just 21, called The Duluoz Legend. According to biographer Gerald Nicosia, it was during a stopover in war-torn Liverpool, while he was serving in the merchant navy, that inspiration struck: "On his last morning in Liverpool that vision of 'beatness' as he later called it, prompted him to conceive of The Duluoz Legend. Sitting at his typewriter in the purser's office, he suddenly foresaw as his life's work the creation of a 'contemporary history record'."

Nicosia's title, Memory Babe, was one of Kerouac's childhood nicknames, earned by prodigious feats of recollection. And indeed Kerouac modelled his project on Marcel Proust's writing from remembrances, telling his editor Malcolm Crowley in 1955 that "everything from now on belongs to The Duluoz Legend". He added: "When I'm done, in about 10, 15 years, it will cover all the years of my life, like Proust, but done on the run, a Running Proust." He hoped it would "fit right nice on one goodsized shelf after I'm gone".

Fearing legal repercussions, however, his publishers insisted he fictionalise his friends and acquaintances into a kaleidoscope of different names. Duluoz (French-Canadian slang for louse) is one of the names Kerouac gave himself, while the poet Allen Ginsberg appears as Carlo Marx, Alvah Goldbrook and Irwin Garden. You'll find William S Burroughs as Old Bull Lee, Bull Hubbard, Frank Carmody; while Neal Cassady, as well as being Dean Moriarty, becomes variations on Cody or Neal Pomeray.

Although some add his poetry – Atop an Underwood and the dream-journal Book of Dreams – to the sequence, for me it works best if you stick to the novels. This means the series that spawned On the Road is effectively celebrating its 50th birthday, given that Visions of Gerard, the opening volume, was published in 1963. It deals with the older brother Kerouac adored, who died when the writer was just four. Written in pencil in two benzedrine-fuelled weeks in his sister Nin's kitchen, Visions of Gerard was called a "pain-tale" by Kerouac: it's the story of an almost divine, Buddha-like child wracked with sickness and suffering.

Visions of Gerard reminds us that Kerouac didn't write the books in order, instead flitting magpie-like through his own memories to write a book about childhood here, a memoir of his Beat adventures there. But it was always his intention that his books should fit together in a neat chronology from his earliest memories to his last days, and be read in that order.

Doctor Sax comes next, mingling Kerouac's boyhood and his love of such pulp fiction heroes as The Shadow with a dark, mythic tale that Ginsberg dismissed as "undigested fantasy". Maggie Cassidy, a paean to his childhood sweetheart Mary Carney, pretty much closes the Lowell years, while Vanity of Duluoz introduces his college encounters with Burroughs and Ginsberg and the birth of the Beat Generation, as these and other writers became known.

This is the point that On The Road finds its place in the legend, when Kerouac meets Neal Cassady. The direct sequel is Visions of Cody, concentrating on Kerouac's image of Cassady as the last great American pioneer cowboy hobo. Lonesome Traveler is more a collection of essays about Kerouac working and travelling around the States. His New York years (and romance with Alene Lee, perhaps one of the few African-American members of the Beats) are documented in The Subterraneans, later a Beatsploitation movie that saw the Alene character whitewashed into a French girl.

Tristessa covers his month in Mexico before the west coast phase begins with The Dharma Bums (marrying mountaineering and Buddhism) and Desolation Angels, in which Kerouac spends a summer as a mountain fire-warden – and, in meta-style, covers the publication of On the Road. The beginning of the end is documented in Big Sur, charting his descent into alcoholism, and concludes with something of a whimper in 1966's Satori in Paris, in which an almost pitiable and lonely Kerouac heads to Brittany to search for his antecedents.

Despite the vastness of a canvas that covers almost 50 years, and the haphazard jigsaw-like manner of its assembly, Kerouac somehow maintains an integrity and a voice throughout all 13 books, each one individual and wearing his latest obsession – a person, a god, a drink – on its sleeve. Nicosia rejects the division some critics draw between the Lowell novels and the Beat ones. "Jack was never capable of making such a distinction," he writes. "Unconsciously, for the most part, he was defining the Legend's central theme – which might be termed 'the loss of life as it is lived' – through the very intensity and urgency of his drive to get it all down."

Rereading Kerouac's novels as one huge, episodic work takes me back to that day I spent at his graveside after pounding through a heatwave. That stone in the ground confirmed that Kerouac took his final trip on 21 October 1969 – 82 days before I was born. But he did achieve immortality of a sort with On the Road. The series stands up proudly to its Proustian inspiration. On the Road will always be Kerouac's heart, but if you're looking for his flesh, blood and soul, you'll find them in The Duluoz Legend. His memories may be fallible, but they are related with honesty and truth. And, as Kerouac insisted, they were put together not from the safe distance of his deathbed – but on the run.