A long novel is a voyage in its own right. You can be changed forever by a work of fiction that's just a few pages long, or even less, but the time you spend with a really long novel – I'm thinking, over 500 pages – breeds a particularly intense relationship. When I was eight years old I read The Lord of the Rings, which took me the better part of a year. By the time I finished it I'd become so used to its 1,100-page bulk that I continued carrying it around for a few weeks. Like the Ring itself, it had become a difficult object to relinquish.

Length presents significant extra-literary challenges to the reader. Shorter work rises to the top of the to-read pile as heavier volumes sink slowly into the unread depths. The investment of time that a long book requires can derail even the most enjoyable reading experiences. A case in point: I recently restarted The Fugitive, the penultimate volume of In Search of Lost Time, having put it down to make a cup of coffee in December 2008.

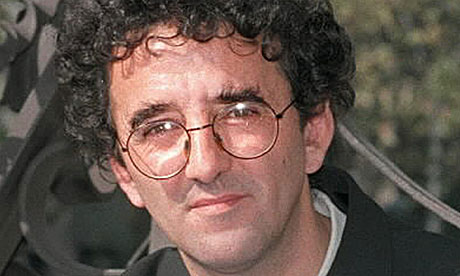

In what Roberto Bolaño intended to be his final novel, 2666, the philosophy professor Oscar Amalfitano considers the difference between long and short books. He remembers an old acquaintance who "chose Bartleby over Moby-Dick" and "A Simple Heart over Bouvard and Pécuchet", and finds it "a sad paradox" that people should be

afraid to take on the great, imperfect, torrential works, books that blaze paths into the unknown … They choose the perfect exercises of the great masters … they want to watch the great masters spar, but they have no interest in real combat, when the great masters struggle against that something, that something that terrifies us all, that something that cows us and spurs us on, amid blood and mortal wounds and stench.

2666 is great, imperfect and torrential. Its pages bear more than enough blood, mortal wounds and stench for it to earn its epigraph, "an oasis of horror in a desert of boredom" (from Baudelaire's poem "Le Voyage"). Bolaño intended it to be published as five separate short novels in order to best provide for his family (he knew he would be dead before it was on the shelves), but its truest expression is as a single, mammoth volume.

Like the majority of Bolaño's work, 2666 is mazy with journeys. Its five sections are essentially various kinds of quest narrative, each of which share as their focal point the fictional Mexican border city of Santa Teresa. Four European academics travel to Mexico on the trail of the reclusive writer Benno von Archimboldi (mirroring the journey the poets Belano and Lima make from Mexico to Europe in The Savage Detectives, one of numerous links between the books). A Chilean academic slides into madness. An American journalist becomes embroiled in violence while covering a boxing match. And Archimboldi's sister comes to Mexico to visit her son, who is jailed there. We follow Archimboldi, too, and his movements east and then west across Europe as a soldier in the Wehrmacht, and after the war as an itinerant writer and, at one point, a gardener in Venice (which is either a joke, a metaphor, or proof that I know less than I thought about Venice).

The date 2666 is a riddle that recurs throughout Bolaño's body of work. He thought of his novels, stories and poems as an interconnected system, and in the short novel Amulet we hear a character describe a certain street in Mexico City as "more like a cemetery than an avenue, not a cemetery in 1974 or in 1968, or 1975, but a cemetery in the year 2666, a forgotten cemetery under the eyelid of a corpse or an unborn child". At the end of The Savage Detectives the poet Cesárea Tinajero appears to be making a prediction about the end of the world when she names a date "sometime around the year 2600". The date seems to operate as a locus or vanishing point for humankind's capacity for cruelty, but beyond that its precise meaning is occluded. As with two of his idols, Borges and Kafka, many of the mysteries in Bolaño's work resist solution.

The Savage Detectives is probably Bolaño's best novel, but 2666 is where he engages most directly with the dark current that runs throughout his work. The book's longest section, "The Part About the Crimes" (300 corpse-choked pages), is a brutal masterpiece that indicts as shallow and nasty the many books that use rape and murder as little more than plot points. Michael Wood identifies this remorseless ordeal of violent death as "Bolaño's tour de force, and a piece of writing sufficient in its own right to give him good odds against oblivion". Because of the section's great length you will be moving through its hostile terrain for at least a couple of days, in which time the malignant force it generates infects the world beyond the page. It becomes an almost physical presence.

Its duration is a fundamental reason why "The Part About the Crimes" is such an extraordinary portrait of malevolence. It is constructed from a multitude of smaller details, and if it didn't drag on as long and relentlessly as it does its effect wouldn't be so profound. As he was writing the book Bolaño referred to it as a "colossal" project, and his friend Rodrigo Fresán sees the book's scope as a conscious attempt to join "the same team as Cervantes, Sterne, Melville, Proust, Musil, and Pynchon". But why would you want to encounter "an oasis of horror in a desert of boredom" in the leisurely days of summer? Because you'll have time to immerse yourself, for one thing. There's never a bad time to read a great book, however dark, however dangerous.