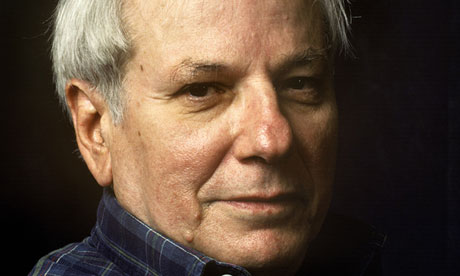

The novelist Yoram Kaniuk, who has died aged 83 of bone marrow cancer, belonged to the generation that created the state of Israel. He fought in the 1948 war from which it emerged independent, but, along with some other writers of his generation, he became disillusioned with his homeland, disenchanted with its very spirit. "The state I took part in founding had ended long ago and I am not interested in what it has become. It is ludicrous, blunt, vile, dark, sick, and it will not last. We used to think it would be different."

In the half century up to his death, he published 29 books, most of them novels, with subjects ranging from the 1948 war, the Holocaust and the occupation of territories gained in 1967 to parent-child relationships and ageing. Among his best-known are Hemo, King of Jerusalem (1968), the story of a wounded soldier in a Jerusalem hospital; Nevelot (Carcasses, 1997), about three old men who go on a murderous rampage against young people on the streets of Tel Aviv; Confessions of a Good Arab (1984), recounting the life of a man of Israeli-Palestinian descent; and His Daughter (1988), telling how a senior army officer's daughter goes missing, and he goes on a journey to find her, and himself.

In terms of style, Kaniuk is identified not so much with his own generation as the next one, and many of his books were adapted for cinema by young Israeli film directors. In the international production of his 1971 novel Adam Resurrected (2008), directed by Paul Schrader, Jeff Goldblum plays a circus entertainer from prewar Berlin leading the death camp survivors in an Israeli asylum. Kaniuk's last book, Ba Bayamim (An Old Man), in which a widow asks a lonely old painter to produce a portrait of her dead husband, was published a few weeks before his death.

Born in Tel Aviv, Kaniuk was the epitome of Israeli "aristocracy". His mother, Sarah, had come from Odessa. His father, Moshe Kaniuk, born in Galicia, went from Berlin to Palestine in the late 1920s and became personal secretary to Tel Aviv's first mayor, Meir Disengof. Later he became the first administrative director of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art.

Yoram joined Palmach – the combat arm of the Zionist militia Hagana – in the period that saw the end of the British Mandate, the UN resolution on partition, and the outbreak of the 1948 war. He took part in some of the battles around Jerusalem: in one, the battle of Nabi Samuel, he and his platoon were abandoned by their commander, a defining moment which reappeared in his writing.

A week later he was injured while fighting on Mount Zion. Once he had recovered, he started working on a ship that brought Holocaust survivors from Europe to Israel.

He was encouraged by one of the period's most acclaimed artists, Mordecai Ardon, to study painting in the Bezalel art academy. In 1951 he continued his studies for a year in Paris.

After another voyage as a sailor, he lived in the US for 10 years, and from there pursued adventure, searching for gold in Mexico and diamonds in Guatemala, and gambling in Las Vegas. He got involved in jazz and cinema circles, where he got to know Marlon Brando, Charlie Parker, Billie Holiday and the dancer and choreographer Lee Becker, who became his first wife. He described those years of the 1950s as, alongside the 1948 war, the most influential on his life and work. "It was the time of the revolution that changed America, and everybody paid for it. It was a powerful experience, the love of jazz, the efforts to become a writer and a poet, the encounters with all the people whom I have hurt, and who've hurt me," he told the daily Ma'ariv in 2003.

He parted from Becker after five stormy years. In 1958 he married Miranda Baker, and went with her back to Israel. They had two daughters, Aya, a writer and political activist, and Naomi, a tai chi therapist.

In 2011 Kaniuk, defiant to the end, won his legal battle when the district court in Tel Aviv accepted his appeal to change the religion clause on his Israeli identity card from "Jewish" to "no religion". Kaniuk explained that while he did not want to convert to another religion, he had never identified as a religious Jew. In addition, following his marriage to a Christian woman, his grandson had been registered as having "no religion". He wanted his registration to match his grandson's.

The ruling is a milestone in Israel's constitutional law. The distinctions between religion, nationality and ethnicity carry vast political implications in the state that defines itself as "Jewish".

He was equally uncompromising about the manner of his exit: there will be no funeral, as Kaniuk donated his body to scientific research and asked for his remains to be burned. "I don't want to leave any bone dust behind. We constitute a chain: one exits, another enters," he wrote in his last blog entry.

He also left a few paragraphs of painful reproach to the Israel he had left behind: "We got trapped. We founded a state on a religion, rather than on the nation that we have nearly become. On our way we have not stopped at the hallway of civilisation, and religion has stuck to us like a leech, as that's its only way to survive, and here it is. It is back. We have not become a nation."

This autumn his memoir of the war, Tashah ("1948", first published in 2010), will appear in French, English, Spanish and German translations.

He is survived by Miranda, his daughters and his grandson.

• Yoram Kaniuk, writer, born 2 May 1930; died 8 June 2013

• This article was amended on 10 June 2013. When Meir Disengof died in 1936, he was not assassinated. The mention of his death has been deleted.