In this future, the past has been forgotten. Not entirely: there are still a few rebels who cling to whatever memories they can pass on, in whispers and in defiance of the law. But all they have are fragments, many of them misremembered. Navigating their way around the ruins of a post-apocalyptic London, they travel up Great Poor Land Street looking for Kings Curse or Waste Monster (perhaps the latter name is not so mistaken). They gather in a slum they know as the Limpicks to worship the giant metal figure of the Red Man – unaware they are in the Olympic Village of 2012, bowing down to the Orbit.

Such is the vision set out in Memory Palace, a new novella by Hari Kunzru and also the centrepiece of a V&A exhibition. Like all dystopias, it aims to say something about our own time. Specifically, it urges us to see the value of today's technology, forcing us to realise how much we would miss it if it were gone. In Kunzru's story, civilisation was destroyed by the great Magnetization, when all digital data was wiped at a stroke.

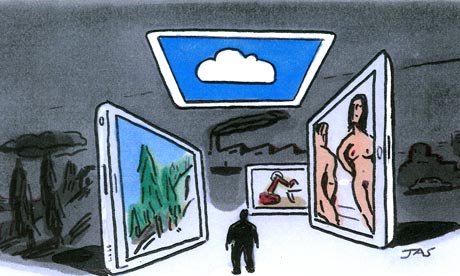

That notion contains a warning about the fragility of memory. Humanity increasingly stores its collective knowledge virtually, in the clouds, making it vulnerable to catastrophic loss. But even without a global disaster, memory is at risk. Things we used to remember – quotations, phone numbers – we now outsource to machines: why learn Kipling by heart, when you can Google it?

More troubling, perhaps, we are depriving future generations of the memory of us. Read the early chapters of Charles Moore's biography of Margaret Thatcher and it's clear he, and therefore we, would have only the sketchiest picture of her youth were it not for the stash of letters she sent her older sister, Muriel. There will be no such letters written by the prime ministers of tomorrow who are adolescents today. Though we now reveal so much more – teenagers especially – we leave behind so much less. Texts, tweets and Facebook updates exist in abundance, but they rarely provide the depth of a letter. And few would bet on them surviving 70-odd years.

The Margarets and Muriels of 2013 are trading Instagrams and Vines, but these exchanges will not linger in an attic to be found at the end of the century; they will vanish, along with the photographs that would once have endured for posterity in thick albums, but which will now be lost, either rendered unreadable by the next generation of technology or discarded with the hard drives that held them.

The point is that a fundamental aspect of human life – memory – is being altered by the digital revolution, and it is far from the only one. I confess I long avoided bowing to such a conclusion. In the 1990s, I was among those who wanted to believe the internet represented a shift in scale or form, rather than in kind: emails would be the same as letters, only faster. But increasingly, it seems, that was to underestimate the nature of the change.

Take two areas of human activity, both highlighted this week. Initially it appeared as if "cyber-porn" would be no different from the old variety, the screen merely replacing the mag. Now most people accept that the ease and availability of a dizzying range of pornography, easily accessed by the very young, represents more than a change of platform. Images that are now commonplace were once visible only to those who were determined to seek them out, knew where to go and were not ashamed to reveal their appetite for them. Now they can be reached at a click, without fear of disclosure or embarrassment. There is no shame. And that may well be altering, if not distorting, the sexuality of the next generation.

Friday was Stop Cyberbullying Day. The old response, that bullying is timeless, misses two key differences: as has been argued in these pages, the pre-digital tormentor rarely followed his victim into the home, as he can now, and always had to witness the consequences of his actions in the flesh, which for some probably acted as a brake. In the virtual age, both those constraints have gone.

The effect of the great technological upheaval on politics, as social media mobilises protest in Brazil and Turkey, and on privacy has been well-documented, especially since the Guardian's revelations about state surveillance. But the change manifests itself in other, less obvious ways, too. The global response to the death of the actor James Gandolfini prompted the political scientist Ian Bremmer to remark that "Twitter reduces the famous-person-mourning cycle from days to hours," a comment he made via Twitter of course. The speed with which an event becomes old news has deprived us of the time to process experiences, both public and private.

The American intellectual Leon Wieseltier recently told of his fears for reading. "Reading is a cognitive, mental, emotional action, and today it is under pressure from all this speed of the internet and the whole digital world." What's more, he believes technology is shifting our way of seeing the world, that we have become "happily, even giddily, governed by the values of utility, speed, efficiency and convenience", so that we now "ask of things not if they are true or false, or good or evil, but how they work".

Perhaps there was similar angst at the birth of the printing press. But this change is reaching into every corner of our humanness. Once it looked like hype, but now those pioneers seem right: the internet really has changed the world completely – and us along with it.

Twitter: @j_freedland