Poor old big-name publishers. Stick to your guns by insisting on the value of your traditional, print-centric gatekeeping, and you'll be shunted straight to the top of the endangered species list. Pander to the plebs by putting a fancy cover on fan fiction, and you'll be decried as an opportunist whore who has swapped literary values for trending hashtags. It's enough to make you run screaming out of your Bloomsbury redbrick and set up in a cheap little Hackney warehouse with a bunch of fixie-riding digital natives who can knock out a Dickens alternate reality game before breakfast.

For those brave soldiers who have remained in the barracks of trade publishing (the smell of fear and ink catching in their nostril hairs), digital only-imprints must seem like a promising hybrid. First, take a brand that both readers and authors trust. Next, put said brand in a genre-specific digital cage, with a ringmaster offering some editorial and production support. Kick off the show with a few established writers and, finally, allow the unsigned, self-published or unpalatably niche pen-monkeys in to play.

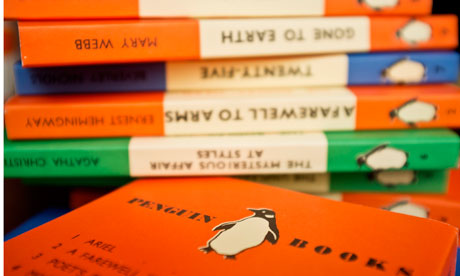

Random House has been one of the earliest and most comprehensive adopters, with Hydra (sci-fi and fantasy), Alibi (mysteries and thrillers), Flirt (new adult, or soft porn) and Loveswept (romance and women's fiction). Harlequin UK has Carina (multiple genres) while Little, Brown is breaking with convention to focus on literary and non-fiction with Blackfriars. This month alone, Penguin, Kensington, F+W Media, HarperCollins and Bloomsbury have announced new or expanded digital imprints. Democracy, speed and low overheads, plus author support and brand heft: what's not to love?

Cue a scandal around the "predatory" Hydra contracts, which have been derided for offering no advance, deducting costs such as editing and design, and retaining rights for the term of copyright. Follow that with Orna Ross, director of the Alliance of Independent Authors (ALLi), pleading with writers at the Literary Consultancy's conference, Writing in a Digital Age, to be "extremely wary" of "the new vanity publishing". Sit back, scroll through your RSS feeds, and watch the name-calling ensue.

"It's easy to see why this option is attractive for a publisher," explains Ross, who recently published an ALLi manual for authors called Choosing a Self-Publishing Service 2013. "They can push books into a growing marketplace at a much lower cost than with a conventional imprint, and reap the profits. From the author's perspective, though, such imprints seem to offer the limitations of digital-only publishing, without providing any of the offsetting advantages available to self-publishers – control over format, publication dates and pricing; creative freedom; better royalties. Authors need to think carefully about what value is being added here and look closely at the contract's terms and conditions, comparing them with what they get if they publish themselves."

But is this an example of yet more publisher-bashing? Should we be giving them credit for at least trying to find a compromise? Evidently, the imprints vary hugely in their aims and approach. "The Blackfriars contracts are conventional publishing contracts," explains Ursula Doyle – Blackfriars co-founder and Virago editor. "We acquire the rights – all for full term of copyright so far, as is usual, but allowing for certain reversions in certain circumstances – we remunerate the author and offer advances, and we bear all the costs."

Doyle is passionate about their integrity. "Blackfriars is a small list by the standards of many digital imprints, and it is as carefully put together as our other literary lists. The books are edited, designed and published in the same way as all our books. We have dedicated publicity and rights people who ensure they have the same shot at serial, review and interview coverage; one of our launch titles, Too Good to Be True by Benjamin Anastas, was serialised over four pages in the Observer Review last weekend. All our authors are remunerated for their work, and all of them so far have representation. We believe that a digital-only launch is the perfect way to publish wonderful books that otherwise might not be published at all, purely because the market for print is so brutal right now."

And what of authors? While some are raging about the small print they failed to read, others are celebrating this new flexible approach. Amy Bird, who has just signed a three-book deal with Carina, and whose first novel Yours Is Mine will be published next month, spent months bashing her forehead against traditional brick walls before the Carina team visited her MA creative writing group at Birkbeck, University of London.

She considers her contract more than fair – there is no deduction or charge for editing, marketing or design, and there are provisions for rights to revert to her after seven years if certain conditions are met. "True, there is no megabuck advance," she admits. "But I don't need an advance: I work part-time as a solicitor. And I am being offered 50% rates on royalties, which seems fair. And most importantly, nobody is asking me to get my cheque-book out."

She believes there are many misconceptions about the industry. "Digital publishing is not about dumping books on a Kindle. From my experience, it is about bright and talented editors finding work that they love and working with an author to get a book the best it can be. With Carina UK, I have gone through all the processes one would expect with a 'traditional' publisher: initial feedback with detailed suggestions for structural revisions; a full copy edit; consultation on title, cover designs and marketing. The amazing thing about digital for me is that I submitted my novel in late February, and it will be coming out in mid-July. Going digital is not for everyone, but for people like me, who have been tweeting, reviewing and blogging for years, it feels natural, exciting, and, frankly, kind of cool."

Of course, the truth of these imprints will be in the storytelling. Until we see them producing consistently exciting work over the long term, neither authors nor readers should be dazzled by their daddy's name. But I strongly believe that we should also get better at taking and celebrating risks. We must allow publishers to fail better, without engaging in continual media mudslinging, or citing specific horror stories as symbols of endemic rot. Otherwise that brave, imperfect future, of which we don't yet know the contours, won't take shape at all.

• This article was amended on 23 June 2013, as it suggested that Ursula Doyle no longer worked at Virago, where she is the associate publisher. This has been corrected