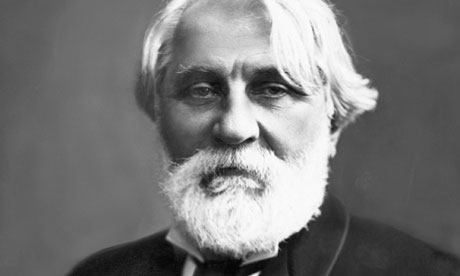

When Gogol died in 1852, Ivan Turgenev, the man whom many in Russia were calling his successor, was arrested for writing an obituary in praise of the great writer. In fact, the official reason was a pretext. Turgenev had already displeased the tsarist authorities with his series of sketches of rural Russian life, published in the journal the Contemporary between 1847 and 1851, and collected in 1852 as Sketches from a Hunter's Album.

This book, which it is claimed influenced Tsar Alexander II's decision to emancipate the serfs in 1861, comprises vignettes of peasant life as observed by a landowning hunter much like Turgenev. Not even Gogol had presented such rounded portrayals of serfs before. As the translator Richard Freeborn notes, while Turgenev would go on to greater things in both the short story and the novel, he was quite aware of the book's merits. At the time of publication he wrote:

"Much has come out pale and scrappy, much is only just hinted at, some of it's not right, oversalted or undercooked – but there are other notes pitched exactly right and not out of tune, and it is these notes that will save the whole book."

Of these, perhaps the one pitched most perfectly of all is Bezhin Lea. This masterful story begins with a description of a July day, and close rendering of the natural world represent one of the deep pleasures of Turgenev's writing. As Edmund Wilson writes, in Turgenev "the weather is never the same; the descriptions of the countryside are quite concrete, and full, like Tennyson's, of exact observation of how cloud and sunlight and snow and rain, trees, flowers, insects, birds and wild animals, dogs, horses and cats behave, yet they are also stained by the mood of the person who is made to perceive them".

Returning home at the end of this glorious day the hunter becomes lost, and as night falls he passes through a landscape of endless fields, standing stones and terrifying gulfs. The mood is that of fairytale, but rather than supernatural beings, the hunter eventually finds only a group of boys guarding a drove of horses. They are gathered around a fire telling ghost stories. Throughout his story Turgenev, the committed realist, repeatedly balances the unreal, the ghostly, with the simply human, fantastical terror with everyday pathos and empathy. The little ring of storytellers, gathered in a small patch of flickering light on a vast plain, effortlessly coexists as concrete setting and existential symbol. At the story's end, when the narrator reports that one of the boys died the following year, he moves quickly to defuse any supernatural tension. As Frank O'Connor notes, Turgenev did not want "the shudder of children sitting over the fire on a winter night, thinking of ghosts and banshees while the wind cries about the little cottage – but that of the grown man before the mystery of human life".

Although Turgenev did occasionally explore supernatural themes, particularly towards the end of his life, his greatest achievements in the short story have love and youth as their main themes. He was at his best when writing autobiographically, and two of his finest stories, the novella First Love (1860) and Punin and Baburin (1874), draw deeply on his own memories. Near the end of his life, Turgenev said of First Love: "It is the only thing that still gives me pleasure, because it is life itself, it was not made up … First Love is part of my experience." This long and beautiful story powerfully evokes both a teenage boy's experience of love, and the complex sorrow of an older man looking back on his youth. The story unfolds over a summer when the narrator, Vladimir Petrovich, becomes one of a number of suitors clustered around Zinaida, whose mother is an impoverished princess using her daughter as bait to lure a wealthy husband. This story sees the first full flowering of Turgenev's ability to create and move between distinct, remarkably vivid characters and points of view, displaying what VS Pritchett calls the "curious liquid gift which became eventually supreme in Proust".

If this liquid sense infuses Turgenev's work as a whole, its point of origin is the individual phrase. Wilson writes: "Turgenev is a master of language, he is interested in words in a way that the other great 19th-century Russian novelists – with the exception of Gogol – are not." Constance Garnett, whose translations introduced most of the great 19th-century Russians to English readers, considered Turgenev to be the most difficult of them to translate "because his style is the most beautiful". "What an amazing language!" Chekhov wrote when rereading Turgenev's 1866 story The Dog. Whether writing of ponies groomed until they are "sleek as cucumbers" or the "steam and glitter of an April thaw", the large edifices of his stories are always built brick by brick, with immense and detailed care. In Death, from the Sketches, he describes the scene of a terrible accident:

"We found the wretched Maxim on the ground. Ten or so peasants were gathered round him. We alighted from our horses. He was hardly groaning at all, though occasionally he opened wide his eyes, as if looking around him with surprise, and bit his blue lips. His chin quivered, his hair was stuck to his temples and his chest rose irregularly: he was clearly dying. The faint shadow of a young lime tree ran calmly aslant his face."

That last detail is a master's touch, all at once visually anchoring the scene, conveying nature's indifference to Maxim's plight, suggesting the border between existence and oblivion, and underlining the solitariness of the moment of death as the observer notes a detail that Maxim never would. Turgenev may not have written quite as often as Tolstoy about the actual moment of dying, but was perhaps equally skilled at summoning the twin currents of dread and banality it so often encompasses.

Turgenev is a poet of disappointment, whose rapturous descriptions of youth are always filtered through an older consciousness aware that it "melts away like wax in the sun". The stunning evocation of childhood in Punin and Baburin begins with the words "I am old and ill now". In an essay of 1860, Turgenev divides heroes into prevaricating Hamlets and mad Don Quixotes, who get things done. As that distinction suggests, action in his work is often troublingly problematic – Baburin's costly outspokenness before his masters, Harlov's fatal destruction of his home in Turgenev's version of King Lear, A Lear of the Steppes – while inaction proves no more profitable (witness the pathetic figure described in The Diary of a Superfluous Man). Yet for all this sorrow and anguish, which led Henry James to speak of Turgenev's collections as "agglomerations of gloom", his stories pulse with a life as vivid as any in literature. In Fathers and Sons, one of the great novels of the 19th century, Turgenev writes of a character's "quiet attentiveness to the broad wave of life constantly flowing in and around us". It's this that his work channels, a wave that carries us ineluctably to our end, but that also contains all the powerful, fleeting beauty of existence. As Vladimir Petrovich says of love, so Turgenev seems to think of life: "I wouldn't want it ever to be repeated, but I would have considered myself unfortunate if I'd never experienced it."

• Translations from the work are by Isaiah Berlin, Richard Freeborn, Constance Garnett and Michael R Katz.

Next: Sherwood Anderson