"Maps and memories are bound together; a little as songs and love affairs are," writes Adam Gopnik in the preface to newly-released picture book Mapping Manhattan. "The map is a stronger version of the trip than a video might be; it is almost a stronger version of the trip than the trip is. I look at the subway map of New York, see the dull line of numbers – 33, 42, 51, 59 – and they fill you at once with memory. Maps, especially schematic ones, are places where memories go not to die, or be pinned, but to live forever."

Gopnik, a staff writer at the New Yorker magazine, was called on to wax lyrical about the joys of maps by his intern.

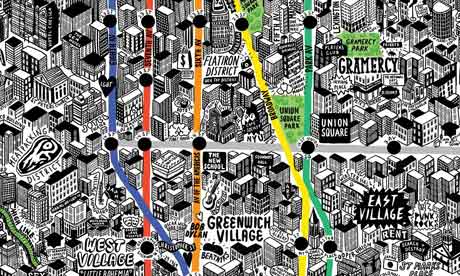

Becky Cooper, a 24-year-old cartographer and writer, had impressed him with her long-running creative side project, where she asked New Yorkers – and visitors – to map their own versions of Manhattan. She took to the streets, distributing 3,000 copies of a hand-printed outline of the island and encouraged participants to "map who you are or where you are; the invisible or the obvious". All copies were self-addressed and stamped so they could be mailed back to her.

Cooper says around 10% of the maps were mailed back and Mapping Manhattan features 75 of the best contributions. Some are heartbreaking (one person mapped key places in his life, from the first apartment he shared with his wife to where she later died); many invoke humour (a map of lost gloves, pictured above); some are confessions (a student who shows how she funded her studies with work at various strip joints). Some are handscrawled in biro, others are collages, and a few use watercolours.

There are a couple of celebrity inclusions, too, including Yoko Ono (with "Memory Lane" scrawled in marker pen through the middle, plus a little heart) and Philippe Petit, the French high-wire artist and star of Man on Wire, who adds a sketch of the World Trade Center towers and a note, "Aug 7th 1974: Walking (illegally) on a cable atop WTC!"

Becky, now 25, says she was delighted by the "honesty and candidness" in many of the responses. "In so many of the maps, the noise of the city just filters down to their personal relationships – which was especially interesting in a city as occasionally impersonal and kinetic as New York." She has since been asked to expand the project beyond Manhattan island to include the city's other boroughs. She also has her eye on Paris and Berlin as destinations for possible follow-ups.

So, why do maps – even the simplest ones – warm our hearts? Is it because the ones we use every day though impressively comprehensive are also now more impersonal then ever. Google, with its reliance on satellites and letting camera-topped cars do the groundwork for Street View, will never have the romanticism of, say, the London A-Z and the heartwarming story – or urban myth – of its founder, Phyllis Pearsall, who personally pounded the pavements, rising at 5am every day and walking for 18 hours, to create her first citywide street map.

One small company helping put the romance back into maps is Wellingtons Travel, which took three years to create a map of modern London in a 1800s style. Their products, designed to be quality souvenirs, range from a giant wall chart to a handheld street map, and even a special commemorative Olympics version with athletes dotted around the venues. "The aim of our London map was to evoke England's history and tradition of exploration. It's not just about navigation; we have our phones for that," says Wellingtons Travel co-founder Taige Zhang.

So are smartphone and GPS maps fuelling a new wave of nostalgia for more unique, personality-filled alternatives? Peter Barber, head of maps at the British Library and author of Magnificent Maps: Power, Propaganda and Art, cites a number of modern artists who are playing with the concept, from Grayson Perry's Map of an Englishman to Stephen Walter's The Island.

Bedroom designers are also causing a stir. The Hand Drawn Maps Association and the Londonist's hand-drawn map series are among the new outlets that have given amateur cartography a real boost.

"The web has put skilled mapmaking within the reach of everyman," says Barber. "Manuscript maps are becoming an art form – a way of exploring ideas far removed from pure geography. With a map, you can transpose a whole reality. Each one is a visualisation of a person's – or a community's – values. Don't be mistaken into thinking any map is factual. Every one is subjective, even Google Maps. It's all about selection."

And that Phyllis Pearsall story about creating her entire London A-Z through on-foot research? "Complete bunkum," he says. "The information she needed was already accessible at the time. She was a great businesswoman and a great employer, but, at the base of it all, she was a real romantic."

And, when it comes to maps, so many of us are.