The Frankfurt school came together and developed its theories in a world left shattered by the first world war. The Weimar Republic was essentially a shell-shocked society in which many of the old certainties had been smashed to pieces. Worse than that, nothing had arisen from the ruins to give anyone any hope for the future.

As liberal democracy failed and Weimar spiralled down into Nazism, this school of almost entirely Jewish-Marxist intellectuals were forced to flee a country which had turned against them for reasons of both race and politics. One of their most cherished members, Walter Benjamin, killed himself in 1940 on the French-Spanish border, an act which threw many of the remaining members into even greater depression.

Changing their country more often than they changed their shoes, as Bertolt Brecht put it, they ended up in the US during the Hitler years and although this was a refuge for them, it was not a society they felt had anything to offer humanity. Ernst Bloch described the US as "a cul-de-sac lit by neon lights" – almost a template for a David Lynch film – and they felt that a society obligated to the pursuit of individualised happiness was the epitome of a world of shallow and inauthentic surfaces and insincerity. In one of the most famous aphorisms from Minima Moralia, published in 1951, philosopher Theodor W Adorno says that it is not possible to live a true life in a false system.

Most important in this context, the thinkers of the Frankfurt school did not draw a great distinction between various forms of capitalism, be they consumerist democracies or fascist dictatorships. Although the surface appearance of oppressive mechanisms were obviously different, for them, the underlying rule of capital was the same.

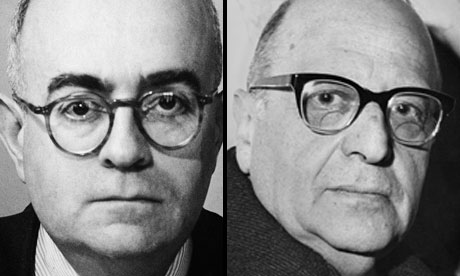

Dialectic of Enlightenment, perhaps the central text of the Frankfurt school, was written by Adorno and Max Horkheimer during these years in exile. It arrives at a pessimistic view of what can be done against a false system which, through the "culture industry", constantly creates a false consciousness about the world around us based on myths and distortions deliberately spread in order to benefit the ruling class.

This is, of course, not peculiar to capitalism, but in capitalism it finds its full commodified form so that we become the willing consumers and reproducers of our own alienation by becoming consumers rather than producers of culture. It is probably a good thing that they didn't live to see The X Factor and OK! magazine. For Adorno and Horkheimer, authentic culture is not simply to be equated with high culture, which is equally commodified. Authentic culture directly resists commodification and punishes audiences for expecting to be entertained.

Leading on from the theory of negative dialectics, Dialectic of Enlightenment argues that enlightenment values themselves are not automatically progressive and that the potentially liberating process of the unfolding of human freedom, as Hegel and indeed Marx posited it, is undermined by our enslavement within the totality of capitalist social relations.

Their view is that fascism, Stalinism and consumer capitalism all produced the widespread socialisation of the means of production and the corporatisation of the economy, with a central role for the state. This convergence had done away with the worst excesses of class exploitation and replaced it with a sort of social complicity between the classes undergirded by recourse to mythologies and ideological control.

This control is exercised not only through direct repression but through the apparently non-ideological aspects of our everyday lives, in particular the ways in which modernity encourages us to fulfil and pursue our desires rather than have them crushed and controlled. Here, de Sade is brought in along with Nietzsche to demonstrate how modernity and the Enlightenment have brought about the transvaluation of all values and undermined all traditions. Marx also noted that in capitalism "all that is solid melts into air". What is often misunderstood on this point is that the Frankfurt School were not the cause of the apparent breakdown of social values but were drawing attention to the way in which capitalism was ineluctably smashing up the old certainties. At the same time as making us enjoy the experience as an extension of our libido we also feel guilty about and transfer the blame for it onto anyone but ourselves.

In an ironic twist, the Frankfurt School, which identified this mechanism of blaming, now functions as the guilty men for those who seek someone to blame.

In the section on antisemitism they explain the ways in which myths about Jews are used by both fascism and liberal democracies to create an outsider group which can be blamed for all problems. This culminates in the Nazi theory that the world is being dominated by a Jewish conspiracy in which rich Jewish bankers finance the communists in order to bring about the dominance of finance capital over good old traditional national productivist values.

Freud is brought in here to say that hatred of the other (in this case Jews, but it can be any other group) is actually a way to mask jealousy of what they have, not in terms of wealth, but in their identifiable collective traditions and apparent social cohesion, which they maintain while the "host" nation rots away around them. Fascism is thus successful not because it is repressive but because it permits and encourages our deepest desires to find the culprit for our own complicity.