The divine counsels decided, once upon a time, that influence is bad and that too much agency is the enemy of invention. Harold Bloom can't be blamed for that: he certainly pointed to the danse macabre of influence and anxiety, but to him the association was perfectly creative. Elsewhere, writers have always been blamed for being too much like other writers, or too much like themselves, and even now, in the crisis of late postmodernism, we find it hard to believe that writers might live happily in a state of influence and cross-reference. Yet anybody who knows anything about writers knows that they love their sweet influences.

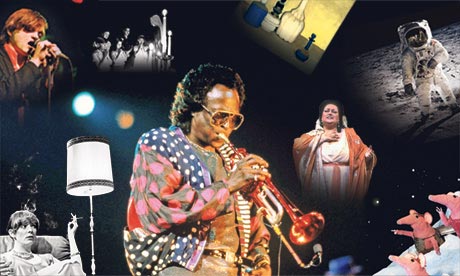

What I've noticed, though, is that the influences that often matter most to novelists – allowing for the occasional big daddy glowering over your prose – are not writers at all but sublime practitioners in other artforms. You feel that Don DeLillo would probably cash in three or four John Updikes for one exceptional performance artist. Henry James would've thrown Nathaniel Hawthorne and George Eliot to the dogs if only to learn from Tintoretto. And wouldn't Roddy Doyle pogo over several dozen novels by Thomas Hardy to get to a refreshing and resonant gig by Teenage Fanclub?

You wouldn't say Kazuo Ishiguro was influenced by film. But he's great at talking about it and you can sit for hours with him just working out a problem in John Ford. Other novelists take out their passion on a second artform – which might be why so many 19th-century French novelists were such good critics – before returning to their own work and breathing a sedate, measured, experienced tone into it. Ernest Hemingway clearly got a buzz of that kind out of bullfighting and fishing, not merely testing the grace under pressure thing but gaining an understanding of action that then influenced how he worked it on the page. Vladimir Nabokov would certainly have sooner spent time with a lepidopterist than with a novelist heavy with prizes. I'm always trying to say it to young writers who seek advice: get a job, take the tube, fall in love with an old photograph. Find a second artform and become an expert in it, a lover of it, a student of its secrets, a master of its techniques, as opposed to sitting around all day thinking about David Foster Wallace.

A novelist is someone who might respond professionally to the sound of a piano in another room. She is someone who lives in the ether of other people's creativity as well as her own. And I wanted to put that to the test with a series of events in May, asking novelists to ruminate on another artform, feeling that an author's work is often best illuminated by side-light. Among the divine counsels, I hope that Roland Barthes still has a voice, insisting on joy as much as others might insist on anxiety. But the correspondence between artforms that I have tried to open up in this series must rest with the thoughts of the novelists themselves, six of them, who ponder what it is in a second artform's arsenal of magic that holds them, possesses them, guides them, or just pleases them.

Kazuo Ishiguro on film

Andrew O'Hagan called recently to tell me he and I were soon to talk about the art of cinema in front of an audience made up, to a significant extent, of film students. Andrew, as well as being a novelist, essayist and playwright, is a film critic, so I have a plan. When this event comes around, I'm going to ask him (and these film students) a question that's puzzled me for years: why does cinema – which does so many things so well it makes the novel look feeble in many departments – struggle so conspicuously when it tries to depict memory?

Yes, I realise the flashback is integral to many classic movies. American noirs especially favour stories told in retrospect, with a voiceover by a desperate, dying or imprisoned narrator anxious to explain how they got where they have. Or there are those films recalled in tranquil old age, such as The Go-Between or Titanic. But in these films, memory is simply a device, a way of ordering the story-telling. Once the remembered scenes open before us, there's no attempt to capture the texture of memory or its characteristic ambiguities.

Of course, there are films that convincingly show people in the act of remembering (not what I'm talking about here) or ones about amnesia (Memento, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind). And films thematically about memory (Solaris, After Life, Vertigo). But when a film-maker goes all out to capture the remembered world, it's always been with limited success. (Time Regained or Mirror – whatever the other merits of these fine works.)

Any reasonably skilled novelist can evoke on the page the texture of memory, drawing the reader into the half-remembered, the blurred edges, the nervous nostalgia, the meandering associations across time and geography. In contrast, flashbacks on screen tend always to be clumsy beasts, announcing their arrival with unwanted fanfare and knocked-over furniture. Why is this? Why, when film-makers throughout cinema history have triumphantly recreated the worlds of fantasy and dream (from the silent expressionists to Tim Burton, David Lynch and Guillermo del Toro today), have so few managed to depict the world of memory?

I do have one tentative theory. Could the problem be that movies are about moving pictures and we tend to remember in stills? I made this suggestion once at a literary festival in response to a question about the memory sequences in my novels, and I could see people exchanging looks and pulling faces, so it could well be there's something very peculiar about me. But I find I recall a scene from my past not as a flowing narrative, but – at least initially – as a picture, or tableau vivant, the details of which I then come back to again and again to interrogate. It's somewhat like the way a lecturer might project the image of a painting on a screen and talk about it. Maybe that's why, for me, the one film that comes closest to memory is Terence Davies's Distant Voices, Still Lives in which each "chapter" centres on something very like a still. I'll raise this with Andrew. I'm hoping somebody or other can come up with a good explanation.

Lavinia Greenlaw on television

I probably spent as much time watching television while I was growing up as I did listening to music or reading. We didn't have a colour set till I was 17, and I suspect this has something to do with my tendency to describe everything in monochrome.

My earliest television memory is of being taken to a neighbour's house to watch the 1969 moon landing. For me, the great event was the set itself – a small, juddering, black-and-white picture trapped inside a lot of dark wood. Around that time, a Japanese friend invited me home for tea. We knelt at a low table while her mother served us tiny portions of beautiful things. Afterwards I was taken to admire her father's television, the first colour set I'd seen. My lasting impression was of the kind of colour I've come to associate with migraines, a dull brightness that makes everything look like old sweet wrappers. We didn't watch it so much as look at it.

My parents bought a set when I was about eight and I discovered the joy of the series. For a child, this was like returning to a favourite book only to discover a whole new chapter, or opening a door to find friends waiting outside. Who cares if they look like stuffed socks and hang out on a blue planet eating soup? The Clangers was just the right combination of the familiar and the fantastical. By the time I wanted something more earthbound than The Clangers, there were the teenagers in The Tomorrow People. They had the same bad haircuts and spots as we did, only they could teleport. Later, the teenagers I watched made a virtue of being ordinary. Grange Hill seemed much like my Essex comprehensive. I'd come home from school and watch school.

By 13, I was hooked on Crossroads, Coronation Street and Upstairs, Downstairs because they were what was available. I didn't notice wobbly backdrops or wooden dialogue or the actors' names. I was compelled by a version of life that was packed with crushes, secrets, stand-offs, coincidences and moral dilemmas. I wanted to be the girl who worked in the chip shop in Weatherfield or the one who blacked the grate in Eaton Place as much as I ever wanted to be Orlando or Anna Karenina.

Over a hundred years earlier, I'd have been waiting a month for each instalment of Martin Chuzzlewit or The Brothers Karamazov. Instead, I had to wait a week to discover whether he died or she said yes or who was holding the gun. I was absorbing the rhythms of the episodic structure and learning what it meant to sustain rather than simply create a world.

A dramatic world that has the time to establish its own natural laws and which operates within the bounds of character can test both these constraints to the limit. This is the fundamental pleasure of such peculiarities as Green Wing or Gavin & Stacey or, on a different scale, Breaking Bad. I grew up with television as an event. It dictated when a show happened and you stopped what you were doing to watch it. There was no chance to catch up. It was my first, and for a long time only, experience of modern drama. Alan Plater, Dennis Potter, Alan Bennett and Fay Weldon were writing for slots such as Play for Today, which included such seminal work as Abigail's Party and Blue Remembered Hills. I developed a taste for tightly choreographed, stylised versions of everyday darkness, which is pretty much what I try to write.

John Lanchester on video games

What's exciting and interesting about video games – note that those are two different qualities, as things can be exciting without being interesting (The Dark Knight Rises) and interesting without being exciting (the Vickers report) – is their newness. Video games are the first new artistic medium since television, but they are more different from television than television was from cinema; they are the newest new thing since the arrival of the movies just over a century ago. That automatically makes them attractive, from the novelist's point of view, as part of the job of the novel is to be interested in the new: there's a reason it's not called the oldvel.

The artistic impact of video games goes in two different directions, the first of them innate to the new medium: what is it that this new thing does that's new, and what is it that it does that's old, but done differently? What are the formal demands made by the new medium? Does it tell stories? If it doesn't, what does it do? How much creative space is there inside it, or have the money men already taken over? (The prevalence of blockbuster sequels and franchises in video games, so early in the history of this art but so similar to the disaster that's happened in Hollywood, is a grim omen.) What does its audience want from it? Does the new form have a new audience – an audience that it is in effect creating, as television created a new public? It's fascinating to see these questions being worked out in real time: on the one hand, the imaginative freedom and openness of a game such as Journey, on the other, the oppressive franchisitis of Black Ops 2, which, for anyone who's keeping count, would be more accurately known as Call of Duty 9.

An early and tentative finding about this new medium is that the most distinctive thing about it concerns the player's agency. Yes, video games do story and spectacle, and there's a particularly distinctive aspect to their sense of progression, of moving through levels, and their experimenting with difficulty and frustration and repetition as part of the form. All of that is good stuff, but the really new thing about video games is the fact that the player in them has agency: she makes decisions, makes choices, has a degree of control. This control is sometimes illusory – choosing from a short menu of predetermined outcomes – but sometimes not, and the momentum inside the medium seems to be towards ever greater freedom and agency for the player. Increasingly, it's the case that the player makes the story, makes the game-world. This gives the medium a real kick of intimacy and force: at its best, it can take you inside the world of a character with a force whose only rival – I find to my surprise, as that wasn't at all what I was expecting when I started taking an interest in video games – is the novel.

This takes us to the second impact of the new medium, which concerns its effect on older forms. Photography brought a lot to painting, because it forced artists to think about what painting could do that photography couldn't. What will video games do for the senior media? There's a curious link between video games and the novel, and it is to do with the experience of being inside a world created by somebody else, but having the freedom to make up your own mind about what you find there. The novel takes you further and deeper inside someone else's head, but the aspect of agency inside video games, the fact that you can make choices that genuinely affect the story, is fascinating and genuinely new. I'm sure that there's going to be some hybridisation between the two forms: a new beast, slouching towards us carrying in one hand a Dualshock controller and in the other a copy of A la recherche du temps perdu. I'm eagerly looking forward to meeting the beautiful mutant.

Alan Warner on pop

Calibrating how something as ubiquitous as pop music has influenced your writing feels similar to asking, "How has the weather influenced your writing?"

While I love all types of music, pop and rock certainly appear in some (but not all) of my novels. I would only reference music on the page if it served some narrative function: like the carefully prescriptive, indexed lists of song titles and artist names in Morvern Callar, which enforced Morvern's methodical approach to life – and to death; here the individual timbres of the songs seemed appropriate to the mood of the drama. On her old Sony Walkman, Morvern is listening to the music of her dead boyfriend (not always pop: there is jazz, Weather Report, Manuel de Falla and Luciano Berio). I get the impression Morvern is haunted and perplexed by this music, listening objectively but not necessarily with pleasure.

In The Stars in the Bright Sky – where the girls dance on one of those EZ Dancer arcade machines – the music had to consist of songs that such a device might conceivably play. The pop song "Kung Fu Fighting" is not a musical composition greatly to my taste – but it was suitably manic, the lyrics wonderfully inappropriate. So I may not always reference music I necessarily enjoy. It is just what fits the narrative requirements in this world so dressed in song.

I have learned there is real danger listening to music while I'm writing. The moving, dynamic power of great pop songs can soon fool you into believing what you are writing is also dynamic and emotionally powerful – it is the music you are reacting to, not your writing.

Pop music functions as this huge repository of personal emotion because it is among these songs and sounds, on radio and at dances and on television, that our young hearts come alive; all this music continues to live for us as a vital thing, both linking us to our past but able to energise us in the future – and a growing library of new songs are added as life goes along. But though I am aware of this personal emotional heritage, as a writer I have to construct the emotional architecture of my characters – you can't just chuck in a few so-called "popular cultural references" for effect. When I was 15 and even more daft, I tried to give up rock music and listen only to orchestral – so-called "classical" music. I was always a real sucker for self-improvement (still am) and I thought I could only become a refined writer if I censored aspects of the real world. I did develop a love for Bartók, Stravinsky and Ravel but I kept coming back to rock and pop music – not fiddles and accordions but heavy metal was the real folk music of the small Scottish town I grew up in. All the guys in our town pipe band practised drums and chanter but listened to Deep Purple; it was simply my culture and I became weary of denying it.

Of course, some pop music is not popular at all and it doesn't try to be; after punk, bands such as the Fall, Devo, Public Image Ltd, even Miles Davis, showed a healthy disregard for audience approval and they seemed to be attacking the very forms that they functioned in. I was mesmerised by that mocking arrogance and such conviction. I wanted to write like that. It was pop music that helped me decide that great writers could come to me on my own terms alone. How were they attacking the form and the world around them?

Now, I adore late Beckett, but it would have been fun if old Sam had been recorded, quietly telling some American professor, "I enjoyed the new Devo long player." I would have felt great vindication.

Sarah Hall on painting

Art history became an A-level option at my school the year I started sixth form. This happened because another student and I cajoled and bullied the head of the art department into arranging it with the examination board. My primary ambition at the time was to avoid taking French. Secondarily, I wanted to hang out with the proper art students who were cool, sardonic, wore hipster clothes, and inhabited a separate annex building where music was allowed, smoking was more or less sanctioned, and you could see the rugby team practising on the pitch. I was a terrible painter – my portraits looked like the evil chimera love-children of Picasso's demoiselles and the BBC test card clown. Writing about it was the next best thing. I managed a B grade. Va te faire foutre, français!

I went on to study art history and English at university. Aberystwyth art department was also satellite, a backstreet repository of goths and geniuses. The alchemical smell of paints, solvents and Golden Virginia was brilliant and heady. And it was a radical department, academically. You could choose almost any kind of module: Aboriginal dreamtime land-art, museum and gallery studies, baroque sculpture, Northern Irish wall murals, treen and bargeware, EJ Bellocq's Storyville prostitute photographs, Oceanic petroglyphs. Of all the humanities degrees, art history is probably the most unlikely to provide vocational remuneration. But the course opened up a world of ideas and interpretation. Not just that, it opened up my imagination; it made me think about the relationship between human existence, art and language. Aspects of that three-year foundation have followed me – no, they have propelled me – into print. The Electric Michelangelo is about that most fascinating, strange and uncompromising of the folk arts – tattooing. How to Paint a Dead Man features a reclusive, Morandi-like painter, a modern British landscapist, a blind girl pursued by a demon that has escaped from a Renaissance masterpiece, and an innovating London curator. The title itself is derived from Cennino Cennini's Il libro dell'arte, an early 15th-century manual for craftsmen, in which there is an instructive section, among the many instructive sections, about painting (pictures of) corpses.

It's been noted that writing about the production of art is a masquerade or metaphor for writing about writing. This may be true, there are similarities – both the verbal and the visual represent the thing or the concept. Long, dementing hours alone might be spent trying to perfect these representations. There are certainly stories that can be taken from the rich world of painting. Some writers have chosen to create fictional biographies of particular artists, usually artists with torrid, dangerous or sexually adventurous lives. I'm more likely to investigate an artist's preoccupation: such as notions of sufficiency – see Morandi's bottles; or indelible commemoration, insignia, and self-ornamentation – why do we want to be marked, and why would anyone want to wield the inky needle? Other influences are more direct: I'd like my literary landscapes to be as atmospheric and as powerful as those painted by Caspar David Friedrich. The beauty of inter-disciplinary conversation is that the mode of expression is essentially different for each practitioner, even if ideas are shared. This gives licence to bastardise and also allows a sense of originality. In translation from canvas to page, so much is lost, reconstituted and developed. And so much inspiration is subliminal. I can stand in front of a painting and simply not know why it makes me want to write.

Colm Tóibín on opera

Fiction begins to roll when an idea, a memory, or something imagined or heard or seen, moves into rhythm. Although this happens silently – words on a page are silent – it comes nonetheless with sound. It is the rhythm of prose that hits the reader's nervous system, and all the more powerfully for being buried in silence, or disguised as silence. Also, although reading is usually done alone, there is something strangely communal about it. It would not do somehow to be the only person in the world who would ever read Madame Bovary or Dubliners or The Portrait of a Lady.

Even though one reader might never meet the others, the fact that those readers are there, and might be there too in the future, seems to matter to the process of reading. I would not like to be alone in reading a book I admire. I do not know why this is the case.

It also matters at the performance of an opera that there are others in the theatre, despite the shadow of Ludwig II of Bavaria who wanted to have all the fun on his own. People you will never meet and may not even like. They add emotional ballast to your own emotion.

There is something else that happens during the live performance of an opera. At least, it happens to me. I become slightly unsure of my own full existence. I am all eyes and ears. There are certain moments when I can feel a beautiful loss of sharp and clear personal identity. I could almost be anyone else. This, seemingly, is what happens to other people when they take drugs.

That uncertainty, the giving of yourself over to the music on the stage and the drama and lights, has a complex emotional texture. Sometimes it goes outwards and the way of listening is sharp; it is easy to feel that life itself, during a soaring aria or a moment when a melody lifts, is at its most perfect and pure. Or just that the music is perfect and pure. To hell with life!

The other part is when I lose concentration. Then the power of the music or the singing moves inwards, and I start to let my mind wander. A few times over the years, some way of handling a new novel, or a way of ending a short story, can come here in the dark more precisely and exactly than before, prompted by the music. And then I sit up and feel guilty and go back to listening as carefully as I can.

Some opera houses have for me become sacred spaces, most notably the Theatre Royal in Wexford in Ireland where three operas are performed, as part of the Wexford festival opera, each October. This was the first time I saw a live opera. I was 16 and it was Bizet's The Pearl Fishers. I remember the lighting and the sound of the chorus and then the main duet rising above Wexford itself, it seemed. Even a hint of that music brings me back to that night, that time.

And then there was the Met in New York on Good Friday 1989 and $5 for standing room for six hours for Wagner's Die Walküre with Jessye Norman and Christa Ludwig in the cast. As the lights dimmed I saw an empty seat halfway down at the end of a row. I walked to it as though I owned it and I sat like a king for the evening.

The best experience I ever had, however, was Montserrat Caballé as Tosca at the Liceu in Barcelona in 1976. For the first opera season when I lived there, I couldn't afford even the cheapest seats. And then I finally bought one.

Imagine my surprise when, after climbing many stairs, there was barely room for my head. And I had no view of any sort of the stage. I could hear the singing and the orchestra clearly, however, as a hungry person can smell food. I felt a rat-like determination to see Caballé just once. Just once.

I waited until she was in the middle of the "Vissi d'arte" aria in act II and about to soar. I leaned forward and put a hand on the left and right shoulder of the two men in front of me. And then using them for leverage I leaned forward some more. And then I caught a glimpse of Caballé. She was magnificent. The two guys went nuts, of course, and afterwards they threatened to throw me down into the pit. But I had done it. I had seen the diva hit a high note.

I have had wonderful adventures with opera since then, but nothing that has ever matched that moment for pure, rare, forbidden excitement.

• The Joy of Influence: Six Novelists on Another Artform 1-22 May at King's College London, Strand WC2R 2LS. Free, but must be booked in advance, kingsculturalinstitute.eventbrite.co.uk

• This article was amended on 29 April 2013. In the original, Kazuo Ishiguro's text referred to the films Mirrors and After.Life. This has been corrected.