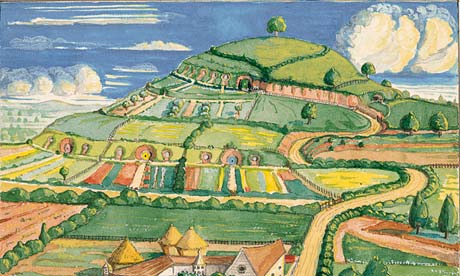

The film series of JRR Tolkien's The Hobbit is unlikely to come anywhere near matching the author's own visualisation of his imaginary world. We know what director Peter Jackson thinks the landscape of Middle Earth is like, from his previous films of The Lord of the Rings, as well as pre-released images from the first instalment of The Hobbit. Jackson's use of location to make the fantastic seem real is impressive. Yet his images are ponderous compared to the ethereal drawings and paintings in which Tolkien pictured places such as Rivendell and the Shire.

Tolkien imagined his otherworld of hobbits, elves and wizards in pictures, as well as words. The Hobbit was first published in 1937. As he wrote it, in the 30s, he made beguiling pictures and designs that map and depict the landscapes through which Bilbo Baggins was to journey.

Tolkien designed the cover for that first edition of The Hobbit. It immediately promises a rich and strange world within: layers of trees in green, white and purple fold over one another towards stylised mountain peaks and the great disc of the sun. Runes are inscribed along the edges of the design. Runic writing is the script of the elves in Middle Earth – but Tolkien did not invent it. Runes were used by the Vikings to inscribe memorials and spells. The Viking connection is telling, for Tolkien's art has a Scandinavian quality. The dreamlike elegance of The Hobbit's original cover is reminiscent of modern northern European art as well as ancient Viking designs.

One artistic cousin of Tolkien is the Russian early 20th-century painter Nicolas Roerich, who was fascinated by the journeys of the Vikings into medieval Russia. Roerich's pictures of the Vikings share the intense quality of Tolkein's art. Roerich is most famous for designing the revolutionary ballet The Rite of Spring. The affinity between his vision of The Rite of Spring and Tolkien's images of Middle Earth is striking.

Tolkien, in other words, is a fine modern artist. His vision of The Hobbit in his original illustrations is very different from the bog-standard digitised fantasy art of today. Tolkien's Hobbit pictures are subtle, even abstract. A scene called The Trolls that he drew for The Hobbit depicts a curling, fantastical flame rising amid a nocturnal labyrinth of stippled trees. His painting Bilbo Comes to the Huts of the Raft Elves is a misty golden landscape you just want to walk into.

It is this sense of place, of a place so real in his mind that he can map or draw it, that makes Tolkien the greatest of all modern fantasy writers. His beautiful works of art reveal the crystalline eye of his genius.