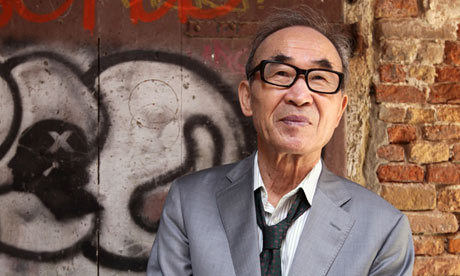

Ko Un, Korea's most famous poet, ended an interview on Saturday not with a poem, but a song. This octogenarian stood up in front of a room full of people and began to sing, at first quietly, then belting it out. There was absolute silence when he finished. It was an extraordinary ending to what had been a glimpse into a most extraordinary life.

Not published in the UK before – although he's better known in America – Ko Un was at the Aldeburgh poetry festival launching his first British collection, First Person Sorrowful, just released by the admirable Bloodaxe Books. He's not a poet I'd previously known much of beyond his obligatory yearly mention as one of the frontrunners for the Nobel, but I've spent the past few days engrossed in First Person Sorrowful, and in what I've learned about the poet himself.

What a life. Ko Un told us about what first moved him to become a poet – and in particular to write the personal poetry which has broken new ground in Korea, and which includes the astonishing, 30-volume Maninbo (Ten Thousand Lives), part of an oath made in prison that every person he had ever met would be remembered with a short poem.

"Until I was in my later teens I had no idea I might be a writer," he said though his translators, Brother Anthony of Taizé and his wife, Lee Sang-Wha. "I was a child like all the children in my home village – I slept, woke up, ate, worked, just an ordinary kid." Then, walking home one evening, came a revelation: "It was already dark, when suddenly I saw something gleaming. It was a volume of modern poems."

The book was the leper-poet Han Ha-Un's first published volume, and it wrought a huge change in the boy who found it. "It was poems written by a leper," explained Ko Un. "He'd written these very sad, mournful poems as he roamed about the Korean countryside. Somebody had bought it and then abandoned it by the roadside. I felt it had been left there for me. I read it and read it all night through. That morning, I woke up and vowed to myself that I would write poetry like this man, and that's when I became somebody who was determined to write poems relating to my own life."

Then, the Korean war began. "Half of my generation died," Ko Un continued. "And I survived. So there was a sense of guilt, of culpability, at being a survivor. They had all died, and here I was, still alive. So from that time on I'm inhabited by a lament for the dead. I have this calling to bring back to life all those who have died. Freud says the dead have to be left dead. Derrida said the dead are and should be always with us, not abandoned. I'm on Derrida's side. I bear the dead within me still, and they write through me. Sometimes it's not me writing at all. It's they who are writing, they are there, ahead, a live presence in what lies ahead. This world of ours in the end is one huge cemetery."

In a newsletter given away at the festival, Brother Anthony revealed more about Ko Un's life. Witnessing the massacres of the Korean war at first hand "left him deeply traumatised. He tried to pour acid into his ears to block out the 'noise' of the world, leaving one ear permanently deaf." He became a Buddhist monk, publishing his first collection in 1960 and leaving the Buddhist clergy in 1962. He began drinking heavily, developed chronic insomnia, became a literary figure in Seoul.

In early 1970 he drank poison, but survived. Ko Un explained more about what moved him to the political activism that led to four periods in prison. "In earlier times I knew nothing except poetry," he said. "Then, in 1970, I read of how a young worker had set himself on fire and killed himself in the struggle for human rights, and for workers' rights. I had long longed to die, tried to die, and reading that account I compared the death I had been dreaming of with that young man's death, and I began to come in contact with and encounter the reality which brought about his death: dictatorship, and all the horrors related to such authoritarian regimes. So I began to cast away the kind of death I had been carrying with me. I began to go out into the streets, in demonstrations against the regime, so of course I ended up in prison."

His third period in prison, when he was accused of crimes including rebellion and conspiring to overthrow the state, was the "most critical", he said. "I was in prison, and confronted with the possibility I might die, so in that situation the only thing left to me was the past. That's when the idea of Maninbo began to arise."

Now 80, Ko Un has published more than 150 volumes of poetry, and you can read some of Brother Anthony's translations here, or take a look at the Bloodaxe collection. Andrew Motion, in his introduction, calls him "a major poet, who has absolutely compelling things to say about the entire history of South Korea, and equally engrossing things to say about his own exceptionally interesting life and sensibility", adding that he's "his own man, and a most eloquent citizen of the world".

Lucky us, then, to have the chance to read him at last.