"Kapuściński" has long been one of Poland's few internationally recognised names, comparable to "Miłosz" or "Polanski". His vivid literary reporting of the uses and misuses of power, in the books The Emperor, The Soccer War and Shah of Shahs, was widely read in the 1980s and beyond, partly because of the author's unique position (a star reporter emerging from the darkness of communist Poland, then in the midst of martial law after a failed workers revolt) but mainly for its unusual style – personal, meticulous, literary, digressive. His wasn't the typical way of writing journalism and, similarly, Artur Domosławski's book is not a conventional biography. Both the author and his "hero", friend and mentor stand out from what was acceptable during the cold war, and today.

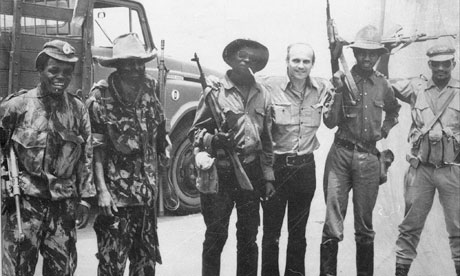

The book caused much controversy when it was published in Poland two years ago (with the title Kapuściński – Non-Fiction). For foreign commentators, the main interest was in discovering how its subject had embroidered the truth in service to style or politics – the fabulations involved his meetings with Che Guevara, Patrice Lumumba, Idi Amin and Salvador Allende. (The Guardian ran numerous pieces in his defence, including by Neal Ascherson and Timothy Garton Ash.) In Poland, the issues were different. Kapuściński's widow tried to stop the book's publication because of its unembellished descriptions of the writer's private life (in particular, his extramarital affairs). But more important than these revelations was Domosławskii's confirmation of the reporter's close connection with various aspects of the communist order, including the intelligence services; his belief in socialist ideology; and his uneasy adaptation to post-1989 realities. In engaging with all this, Domosławski has produced a rare and subtle portrait of the People's Republic of Poland.

Politics in Poland is still largely determined by the past, and after 1989 there have been only two acceptable ways of looking at the postwar era. One is to regard the communist regime as illegitimate, but something after which we can draw a "thick line" between the past and the present. The other considers the system simply as criminal and those who worked within it as traitors – traitors who should be tried. Kapuściński was himself accused of being an agent shortly before his death in 2007; Domosławski gives details of his espionage, in particular the notorious case of him spying on the academic and reporter Maria Sten in Mexico. But the biographer also goes beyond this binary approach to the past, dwelling on and paying tribute to his subject as a lifelong opponent of imperialism. Crucially, while the Polish ex-oppositionist media fervently supported the Iraq war, Kapuściński was a rare figure of the post-communist intelligentsia publicly to oppose the war on terror.

At the time Kapuściński started to gain fame abroad for his reportage, the cold war had entered a new, dangerous stage. He dropped his party card, supported the Solidarity movement, and, pre-empting his American editors, removed potentially inflammatory passages in Shah of Shahs about the role of the CIA in overthrowing the Mossadegh regime. Yet there were proper limits to his flexibility, and Domosławski includes much evidence of his hero's dedication and sacrifice. Plenty of questions have been asked about the "real cost" of his free travel around the world, but Kapuściński didn't gain much when compared with his journalistic colleagues. Friends recall him wearing rags and sleeping in his car. Without doubt, it was political passion and humanism that made him such a profound critic of colonialism in Africa and an enthusiast for the Cuban revolution. And this gave him an insight, unusual in Poland, into the negative role of the US in supporting dictatorships. His reportage from Latin America could have been written yesterday. Yet nothing is simple: did Kapuściński realise his friends in the Polish politburo were involved in beating students and in antisemitic witch-hunts in 1968? After all, his net of connections allowed him to write, and aroused suspicion from persecuted friends.

The constant speculation about the level of Kapuściński's engagement with the regime means that this biography reads at times like a John le Carré novel. The question of identity, of image, of truth, of confabulation, shifts constantly and gains new meanings, turning the book into a quest for Kapuściński's personality. Who was he? Not even his family or close friends are really able to answer.

He was born in the 1930s in Pinsk, a Jewish town that suffered all possible atrocities during the second world war. Although his own life was not in danger, he witnessed the murder of the town's Jews, invasion by the Russians, then the Nazis, then the Russians again – it becomes plausible that everything he did subsequently was inspired by these events. He was from a poor family, and for people like him communist Poland created chances, which he took. Domosławski quotes a friend: "Rysiek produced great work. However, in order to do it, he had to create himself, his own image … He put a great deal of work into it – it was hard for him, but he passed that exam with flying colours. The image of a fearless war reporter. He reckoned without this legend no one would listen to a writer from faraway Poland." That would explain also why he repeatedly claimed his father was nearly killed with 20,000 Polish officers in Katyn in 1940.

When the moment came for coming to terms with the crumbling Soviet empire, he missed his chance. For Domosławski, Imperium (1993), about Kapuscinski's travels to the USSR, is a book written in denial, in which the author – who could have told us the most gripping story of his own engagement and disappointment – disappears. Kapuściński reacts with his most significant act of self-censorship, afraid to present himself in the new Poland as an ex-communist, and choosing instead to present himself as a victim. In a way, the system left no option other than to be both victim and beneficiary – in post-communist Poland there was little space for nuance. The earlier reporter wrote a complex version of history; the feted Kapuscinski of the new Poland was unable to do so. But Domosławski's book brings back the authentic voice of the reporter and hero, and if only for that, it is a truly great achievement.