Why do we find it easier to say "war and peace" than "peace and war"; and why are there plenty of books on the Art of War but barely a single one in our bookshops on the Art of Peace? Why is history so often taught as a succession of wars punctuated by peace, instead of giving equal weight to both?

Of course wars are dramatic and devastating and we need to analyse properly their causes and effects. They can also have a sort of glamour, though more so when seen at a distance. As Arnold Toynbee once observed, "wars are exhilarating when fought elsewhere and by other people".

But civilisation would not have advanced without long periods of productive peace. As the great humanist and peace thinker Desiderius Erasmus (1466-1536) put it, "peace is the mother and nurse of all that is good for humanity". And peace is what most people want most of the time: if war is in our genes then peace is there even more. When I started work on a study of thought and argument about peace from ancient times to today, I found it surprisingly hard to explain what I was doing. Some people simply did not catch the P-word – I had to gloss it by explaining that I was doing research on "the opposite of war", even though peace is actually a good deal more complex than that. Others wondered if I was wasting my time, commenting only half in jest that "it's going to be a very short book, then".

The view that peace is dull is widespread, often supported by an out-of-context quote from Thomas Hardy that "War makes rattling good history but Peace is poor reading". Hardy put these words in the mouth of the aptly named Spirit Sinister (in The Dynasts) – it was not his opinion at all. Even some scholars in the field of peace studies are defensive about their work. Perhaps that is to be expected in view of their uphill struggle over the past three decades against the academic orthodoxy of "realist" international relations.

During the cold war the very word "peace" was misappropriated by both contesting sides. In its early years the greatest Fighter for Peace, according to Soviet propaganda, was a certain Josef Stalin, and the Soviet Peace Campaign always approved of the Soviet bomb. In the west, those who really worked for peace and against war, particularly against the threat of nuclear war, were denounced as naïve and dupes of communism, while the US Strategic Air Command proclaimed that Peace is Our Profession.

In spite of the continual belittling of the term, peace has now acquired a richer and more ample content than in the past. We now understand much better that peace is indivisible, and that our own security depends upon promoting economic and social well-being across the world – that we need to globalise peace as well as economics. Yet when it comes to foreign policy, our governments too often default to the war option, and our media don't hold them sufficiently to account. The crisis in Syria today is presented almost entirely as an inevitable armed conflict. The efforts of significant Syrian opposition groups, meeting in Rome at the end of July, to promote a peaceful solution (in the Sant'Egidio statement), were barely reported. "Hardly any peace is so bad", wrote Erasmus in his Complaint of Peace (1517), "that it isn't preferable to the most justifiable war". With the Iraq war in recent memory, and a re-run over Iran distinctly possible, that is a proposition to ponder. Machiavelli has had too easy a ride for too long: let's give his contemporary Erasmus, and peace, a better chance.

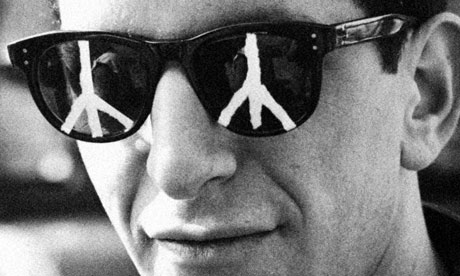

John Gittings will discuss Icons of War and Peace with Martin Kemp at the Edinburgh International Book Festival on Sunday August 26 at 8.30pm