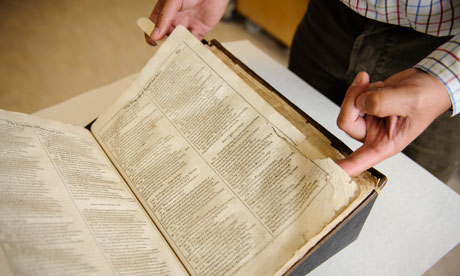

Before they laid a finger on the battered, brown-leather book, the conservators at the Bodleian library in Oxford just sat and stared at it, working out how to do as little as possible.

The sorry-looking volume is one of the most famous books in the world: the 1623 First Folio of the plays of William Shakespeare, published within seven years of his death by his friends and fellow actors, and the only reason the world inherited plays including The Tempest, Twelfth Night, Macbeth and Julius Caesar.

The conservators have already made an extraordinary discovery: far from the traditional story suggesting the Bodleian's was the finest example of the finest work of an Elizabethan printer, a luxury volume for an elite audience, the Stationer's Company may have palmed off a shoddy copy, poorly printed on inferior paper full of production flaws, which should never have passed the quality control standards for paper makers and printers.

Some damage including folds in the paper and torn corners, assumed to be the work of careless hands over four centuries, was almost certainly there from the start. Today the university library launches a £20,000 appeal fund to digitise the book so that anyone in the world can read its tattered pages, with the backing of Stephen Fry, the director Sir Peter Hall, Dame Vanessa Redgrave, and Jonathan Bate, curator of the Shakespeare exhibition at the British Museum, who called it "the most important secular book in the history of the western world".

Scores of copies survive, but the Bodleian's is unique – the buckled splitting leather is the original binding of the loose leaf pages as they came from the printers in 1623.

At the time the rule of the library's stern founder prevailed, barring all "riff raff and baggage books", particularly contemporary plays.

Clive Hurst, head of rare books, said the fact that the First Folio was bound, chained and given shelf space, showed how Shakespeare was already moving from being seen as popular entertainment to the ranks of serious literature,

Most of the shelves had Greek, Latin and Hebrew volumes. The tattered pages of the folio showed that the scholars fell on such rare diversions: Romeo and Juliet was read almost to disintegration, King John left pristine.

The book is also a horrible warning to all librarians of the perils of disposal. In 1664 the library got the much smarter Third Folio, and a few years later sold off the First as a duplicate. It would pass through many hands until one day in 1905 a man walked in with the book in a bag, and asked what they thought of it.

A brilliant young librarian recognised the Bodleian library binding and the scars of the chains: it cost them £3,000, also raised by a public appeal, to get the book back. Since then it has scarcely been opened, and has spent almost all its time locked in a strong room.

Hurst feels very twitchy when the volume is out of the building in the conservation studio.

Permission is occasionally given to scholars who really need to use it, but it was the inspiration of Emma Smith, of the English department, who itched to get her hands on it, to get it digitised and available for the first time to the world.

Every page has to be photographed in the highest possible resolution, and the challenge for the conservators is to stabilise the book so that it does not disintegrate in the process - but without destroying any of the historically fascinating damage, or the heroic efforts of one 18th century owner to carry out homemade repairs.

They had to repair a split in the leather – which, comparison with superb 1905 photographs showed, had lengthened ominously and risked ripping completely – just so they could open the cover.

"Usually when a book comes to us the object would be to restore it to a condition when it could be given out to readers again, but that is never going to be possible, or desirable, with this book," Nicole Gilroy, the team leader, said.

They have made scores of almost invisible repairs with slivers of Japanese paper almost as fine as surgical stitches, attached with wheat-starch glue, and they have straightened out some folds that were obscuring text.

But many more folds in plain paper, or tatters that were not actually about to fall off, were left alone.

They worked in pairs, one with the glue brush, one with a pencil recording every intervention: "The one with the brush always wanted to do more, the one with the pencil was always arguing for less," Gilroy said. "It's in our nature where we see damage to want to repair it."