Last week, according to several reports, hell froze over and the lion lay down with the lamb. On closer inspection, it transpired that the book chain Waterstones had announced it was to begin stocking Amazon's digital book-reading device, the Kindle. Although on the surface this may not seem like major news, within the world of publishing the effect was nothing short of seismic.

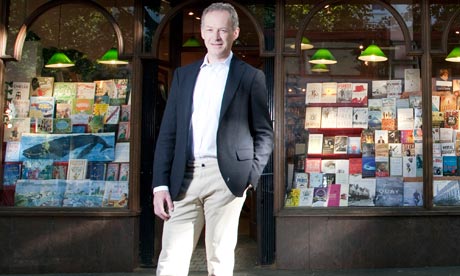

Since taking over last July as managing director of the troubled chain, James Daunt has made several eye-catching decisions. Within three months, to the amazement of many within the book industry, he dropped the three-for-two discount that was the cornerstone of Waterstones' sales strategy. Just as controversially, at least in literary circles, he also dropped the apostrophe from the shop's name. But if those moves proved that Daunt was not afraid to make his mark, few saw this latest initiative coming and with good reason.

Last year, in a series of interviews, Daunt spoke of Amazon as the "enemy" and "a ruthless, money-making devil". With that kind of plain speaking, it seemed sensible to assume that the one place the devil wasn't going to be making money was in Waterstones. Yet Daunt has elected not only to sell Kindles, but also to make it easier to buy Amazon ebooks as part of the browsing experience. If this is supping with the devil, then it appears as though Waterstones gets a teaspoon and Amazon's Beelzebub a whacking great ladle.

Some industry analysts presented the development in even starker terms, suggesting that the fox had been "let into the chicken hut". They pointed out that once Waterstones' customers are linked up to Amazon, their primary retail relationship will be with the online giant rather than high street shops.

"There are many high-spending customers who have been resistant to ebooks and buying online for a variety of reasons," explained one analyst. "But Waterstones' imprimatur will encourage them to overcome their doubts. And then they won't be rushing down to their local branch to buy online – they'll be doing it on their computers."

So is the announcement merely confirmation of Amazon's monopolising power or does it show Daunt's flexibility in an extremely difficult market?

"The important thing to remember," says Neill Denny, editor-in-chief of the Bookseller, "is that Waterstones is rolling out a £40m project that also involves refurbishing 100 stores and putting in good cafes. It's about making a nice physical place where you can also buy ebooks."

Certainly Daunt is a man who believes that a bookshop should be about much more than a place that sells books. "He understands what the attraction of bookshops is better than anyone," says Brett Wolstencroft, Daunt's former partner. "And in a business that can sometimes seem very complicated, he has a remarkable ability to see things clearly."

Wolstencroft helped Daunt set up Daunt Books, the high-end boutique experience for bibliophiles. The story goes that in the late 1980s, when he was in his mid-20s, Daunt left a banking job in New York with JP Morgan to be with his then girlfriend (now wife) back in London. Unsure what to do, he hit upon the idea of combining his two passions – travel and books – to create a literary bookshop with a global perspective.

The first Daunt Books shop was in Marylebone High Street, now one of central London's chichier thoroughfares. It proved a success and gradually six more followed, all of them in well-heeled neighbourhoods. Focusing on distinctive stock selection, a cultured ambience and informed staff, the shops produced a healthy £10m turnover.

One of the shops was in Holland Park, and one of its customers was said to be Alexander Mamut, a Russian billionaire. Last May, Mamut bought Waterstones from HMV for £53m and appointed Daunt managing director.

Despite Daunt Books' recession-defying performance, many eyebrows were exercised over Daunt's new position at Waterstones. Sceptics felt that he lacked the experience to steer a chain with almost 300 outlets. He was seen as a specialist who would struggle to make the transition to the mass market. When he spoke of local branches catering to their local audience, some observers complained that he was trying to turn Waterstones into Daunt Books.

The Daunts can trace their English roots to the Middle Ages and a patrician background did nothing to counter the image of a refined aesthete with no feeling for popular tastes. Born to a career diplomat, Daunt was educated at Sherborne and then read history at Cambridge. Physically, too, he conforms to the picture of a diffident English gentleman – neat, reserved and yet conveying the kind of quiet confidence that takes centuries to cultivate.

He lives in the bien pensant heartland of Hampstead with his wife, Katy Steward, a professional in the health sector, and their two daughters and two dogs. They also have a house in Suffolk, where he enjoys a bracing swim in the North Sea.

"Culturally, he lives in a bubble," said one industry insider. "He's an elitist, a highbrow bookseller. That was good for Daunt, but it's not right for Waterstones. It's like going from managing Torquay United to Manchester United."

But Wolstencroft argues that Daunt's detractors have got the man wrong. "You hear all this talk of public school and Cambridge," he says, "yet he's the least elitist person I can think of. Like any good retailer, he is really just interested in what people want."

As Daunt himself has put it: "I don't care what people buy, so long as it's the right book for them. If I'm helping a woman in the mother and baby section, I'm never going to read the book in a month of Sundays. But I can absolutely tell her which ones are the best ones and why – and I enjoy that process. We as booksellers are about getting the right books for people. We shouldn't dictate."

He describes the elitist tag as "ridiculous". None the less, it's hard to see how bookshops will survive as anything but elitist environments. Between supermarkets stocking bestsellers at reduced rates and Amazon's one-click ease, there is precious little space for large book chains to survive, let alone thrive.

No one knows how the digital revolution will leave the publishing industry, but optimists are not thick on the ground. Wolstencroft believes that what is required at this point are not visionaries, in the sense of futurologists with a fixed view, but people with a clear vision who can also adapt to changing circumstances.

"Nobody called the music industry's changes accurately," he says. "You've got to react, not turn your nose up. And James is very good at reacting."

This may explain Daunt's seeming acquiescence to Amazon. A significant and increasing number of readers are moving towards electronic reading and any serious player in the market must try to respond to that trend. Daunt had hoped that Waterstones would develop its own e-reader as an alternative to the Kindle, as Barnes & Noble has done in America. But, as Denny says, "he ran out of time. He needed to have one ready for this coming Christmas".

The failure to develop what Daunt had dubbed the "Windle" can be attributed to the HMV years of drift, in which the company was neglected and starved of investment. The consequences of that inattention are yet to be fully seen, although they could be profound. In his anti-Amazon tirades last year, Daunt portrayed booksellers, publishers and agents as an interdependent triumvirate under existential threat from the internet behemoth.

"I think either all three will survive or they'll all disappear, swept away, replaced by one big fat Amazon, getting his way," he said. "And if the bookshops go, they will never come back."

For the moment, Waterstones has not been swept away, but it may possibly have handed the broom to big fat Amazon. A nervous British publishing industry will be watching very closely to see if Amazon cleans up in the coming months.

Twelve months ago, Daunt saw himself as the book business's last line of defence against the depredations of Amazon. "I have a responsibility," he said. If that responsibility is weighing heavily at the moment, now is the time for the bibliophile businessman to show that he remains undaunted.