The shabby, 38-year-old American who arrived on the Left Bank in 1930 with a copy of Whitman's Leaves of Grass, and the manuscripts of two unpublished novels in his suitcase, was the quintessence of abject failure. All he had going for him – and it was everything – was creative rage (expressed in one letter as: "I refuse to live this way forever. There must be a way out"), mixed with the artistic vision of the truly avant garde. "I start tomorrow on the Paris book," wrote Henry Miller. "First person, uncensored, formless – fuck everything!"

Four years later, the novel whose working title had been "Crazy Cock" was launched by a French publisher of soft pornography as Tropic of Cancer. Wrapped in an explicit warning ("Must not be taken into Great Britain or USA"), it set a new gold standard for graphic language and explicit sexuality. From the outset, Miller's "barbaric yawp" shook US censorship and inflamed American literary sensibility to its core. Tropic would remain banned for a generation, by which time it had become part of postwar cultural folklore, smuggled into the US wrapped in scarves and underwear. Rarely has a book had such thrilling and desperate underground beginnings.

Finally, in 1961, the year after Lady Chatterley's Lover secured the right to be published in the UK, Tropic of Cancer triumphed in its battle with the US censor and was published by Grove Press. The timing of this landmark verdict did not favour the ageing iconoclast. At first, his book was treated as the fruit of Miller's complex relationship with Anaïs Nin, an object of veneration within the American feminist movement.

There's no doubt that Nin had been a vital muse, but Tropic was always Miller's baby. In Frederick Turner's words, it was "a great, bloody sprawl of a book, an assault on the taste, the patience and the expectations of even the most adventurous of readers". In short, a classic and an inspiration.

When it first appeared in 1934, Tropic of Cancer had been contemporary with Faulkner's Absalom, Absalom!, Fitzgerald's Tender is the Night and Hemingway in his prime. The cutting edge of American prose was rather more genteel than its tough guy image. Hemingway's "up your ass" appeared in print as "you know where". His "fuck your mother, fuck your sister" was rendered simply as "F-----". Miller's visceral candour was off the charts of contemporary taste, in tone as much as language. Miller, writes Turner, took "a fiendish delight in rubbing the reader's face in filth just for the pleasure of it". This short, erudite and highly coloured account of Miller's creative backstory explores both an extraordinary American life and Miller's "renegade" American inheritance.

He was born in 1891 of German immigrants and grew up in a German-American quarter of Brooklyn, full of self-loathing. "My people were entirely Nordic," he wrote, "which is to say idiots. They were painfully clean. But inwardly, they stank." This Brooklyn boy "really didn't give a fuck about anything". He spent his formative years as a handyman, a piano teacher and an employee of Western Union.

By 1930, he was at rock bottom and in dire straits. Turner persuasively argues that it was Miller's deep preference to be "a kind of Huck Finn whose goal in life was to avoid growing up"; a man for whom life was an experiment in creative deprivation.

In this, claims Turner, he was an archetypal American renegade. To the founding fathers such as Alexander Hamilton, these renegades were a threat, a "great beast", whose unruly loquacity was at odds with good government. In literature, the renegade strand would find its richest expression in the genius of Mark Twain, who went out of his way to oppose the "genteel tradition" of Emerson and Longfellow.

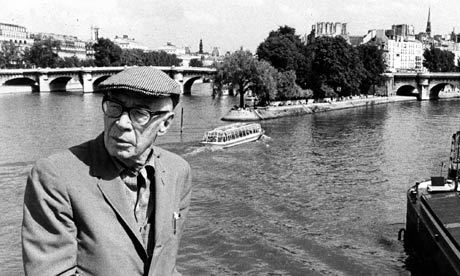

By the 20th century, the renegade frontier was to be found not in the wild west, but in Paris. Miller, the down-and-out literary Apache, revelled in a new frontier of seedy desperation, where there were "prostitutes like wilted flowers and pissoirs filled with piss-soaked bread". He and Anaïs Nin flourished here – resolute, isolated and stoical in pursuit of their new aesthetic. Nin memorably recalled that, while her lover was mellow in his speech, there was always a "small, round photographic lens in his blue eyes".

Among the great writers of the 30s with unblinking, camera vision, it was Miller's "fuck everything" that would inspire subsequent renegades such as Genet, Burroughs, Mailer and Ginsberg. Not bad for a man who had once written: "Why does nobody want what I write?"