"We come here for fame!" was how the Tory prime minister Benjamin Disraeli explained the allure of the House of Commons to a sceptical John Bright. "Bright earnestly insisted that he came there for no purpose of the kind," according to one observer. "Disraeli ceased to argue the point, and listened with a quiet half-sarcastic smile, evidently quite satisfied in his own mind that a man who could make great speeches must make them with the desire of obtaining fame."

Bill Cash has achieved a degree of fame, or notoriety, both as a member of parliament and Methuselah of Euroscepticism. He was one of John Major's "bastards" on the Maastricht treaty, and today continues to make the case for withdrawal from the EU and the repatriation of powers to Westminster.

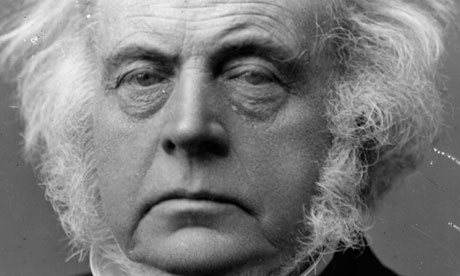

But Cash is also, we discover, the long-lost cousin of the Victorian statesman John Bright. And the result is a welcome biography of the remarkable Quaker, orator and agitator behind the repeal of the Corn Laws, the 1867 Reform Act, and the mid-19th century spirit of pacific internationalism. Out of step with today's Tory party, Cash has found here a politics he can like: laissez-faire, democratic, conscience-driven and hostile to the state. "He was an independent Radical by principle, with a persistent strain of innate conservatism." And this biography is in many ways a meditation on the nature of true, authentic conservatism.

However, as with so many conservatives, Bright began as a radical. Born in 1811 in Rochdale, he worked in the family mill from the age of 15, continuing his autodidactic education thanks to the Society of Friends. But it was on the warehouse floor that Bright became enthused with the spirit of radical, northern nonconformity. "I knew that I came of the stock of the martyrs."

The passage of the 1832 Reform Act inspired Bright to found the Rochdale Reform Association, yet it was economics not politics which first pulled him into public life. "The troubles thrown up by the Corn Laws by monopoly, privilege and aristocracy, were a denial to other human beings by those who benefited from the advantages of being of the landed gentry," Cash writes.

Joining with Richard Cobden, another northern manufacturer, Bright set Britain ablaze in the 1840s as they battled the Corn Law subsidy. And Cash brings out very well the immensely affectionate relationship between Cobden and Bright; indeed, this biography often reads as a cumulative series of intense, male friendships between Bright and such people as Gladstone, Disraeli and Chamberlain.

But the narrative is also well done, as Bright argued the case against privilege and subsidy both in and outside parliament. "The freedom from which you struggle, is the freedom to live; it is the right to eat your bread by the sweat of your brow … I think I behold the dawn of a brighter day; all around are the elements of a mighty movement." Just occasionally, the mask slips as the author's Euroscepticism overrides his scholarship and Cash brings the 2011 eurozone into an analysis of 1840s British trade policy.

After the repeal of the Corn Laws, Bright's focus turned toward political freedom, as "both parliamentary reform and free trade were rooted in the question of freedom of choice". It was a tortuous struggle, with many a twist and turn, which led to the 1867 Reform Act. And even if Cash underplays the role of the Chartists and doesn't pay enough attention to the impact of the 1860s cotton famine, he compellingly describes every lost vote, amendment, and fix. This was how politics should be done. "Gladstone and Disraeli sat opposite each other, John Stuart Mill sat behind Bright 'in constant communication' … The House of Commons reverberated with the thrills and spills of political excitement, invective and moral and political force." This was England: Bright's "ancient country of Parliaments … the mother of Parliaments". And Cash misses it terribly.

There is a similar SW1 focus when it comes to Bright's criticism of the Crimean war campaign. Again, for Bright, it was a question of transparency. Taxpayers' money was being spent on unjust wars by a distant and corrupt state – all embodied in the Whiggish figure of his arch-enemy, Lord Palmerston. "I have not enjoyed for 30 years, like those noble Lords, the honours and emoluments of office," Bright declaimed. "I have not set my sails to every passing breeze, I am a plain and simple citizen, sent here by one of the foremost constituencies of the empire." He ended up supporting Russia against his own government – and losing his parliamentary seat in the process. As Cash reverentially explains, "Bright put conscience, conviction, the working man and his country before party." A familiar refrain, no doubt, in the Tory whips' office.

However, Westminster was the imperial parliament and Bright was nothing if not an internationalist. On India he was on the side of right: he condemned the East India Company for organised larceny, demanded democratic accountability and urged free trade not imperial conquest. On America, in contrast to Gladstone, he was an early and unwavering supporter of North against South. So much so, that among the artefacts taken from Abraham Lincoln's assassinated corpse was a testimonial from Bright urging his re-election. But when empire clashed with Westminster, he was always on the side of parliament – so Bright could never abide Irish home rule if it meant legislative independence from the UK.

This biography is the work of a parliamentarian rather than historian, and Cash spends too little time on situating Bright within his times – on the politics of Birmingham, or the Victorian culture of free trade, or the nature of northern nonconformity. The hinterland is missing. The political life – masterfully recounted – can sometimes feel overbearing. This book is as much about Cash as Bright.

• Tristram Hunt MP is author of The Frock-Coated Communist: The Revolutionary Life of Friedrich Engels (Penguin).