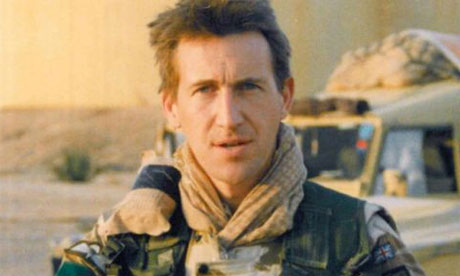

Britain has had some unlikely arts (and shadow arts) ministers over the years. But none so far-fetched, perhaps, as Dan Jarvis, latterly Major Jarvis, company commander in the Parachute Regiment, who won the Barnsley Central byelection last March and is now three months into his role as shadow culture minister. It's a swift rise and it's easy to see what a valuable scalp he is for Ed Miliband's Labour: an officer who has just received an MBE for his military record, and who has been a committed Labour member since his teens. But is Jarvis, whose last frontline role was with the Special Forces Support Group in Afghanistan, right for the job of culture spokesman?

The night before we met, he was helping launch Labour Friends of the Forces, set up to "demonstrate the value Labour places on the defence community". This, understandably, seems more comfortable territory for him than the arts. As Jarvis himself says: "I have never tried to pretend I was in and out of the ballet every night of the week prior to getting this job, because I wasn't." His personal circumstances have also militated against a committed cultural life: his wife died of cancer in 2010, leaving two young children. The children now live in Barnsley, cared for during the week by Jarvis's new partner and other family members; the balance between his domestic life and the draining Westminster merry-go-round is kept workable by being "incredibly well-organised".

Impeccably courteous, with a tough-looking, stringy physique that speaks of military life as well as an abiding love of the mountains, Jarvis's very mode of speech recalls his former career. He talks about bearing "a torch of responsibility" for both Barnsley and the cultural sector. He will, he implies, bring a military vigour to the job: "I need to apply rigorously the standards that I have brought from outside." He talks of the most challenging part of his army career: his deployment to Afghanistan in 2007, when he left his late wife, who had already had two bouts of cancer, at home with their children. "She was adamant I should go," he says. "They were tough, dark times. Politics can be brutal. But I don't think things could ever be how they were at that time in my life. I do think it's given me a perspective. If people say something mean to me on Twitter, it's not the end of the world."

He has set in train various pieces of work he hopes will be of use to the arts, including a "vision for growth through our creative industries". These industries, he says, "are a massively important sector of the economy. They account for 8% of GDP, put £50bn into the economy, millions of pounds of exports, two million jobs." Jarvis comes out with such figures as if they are a revelation, which perhaps they are for him: it's a reminder that he is coming at the subject from a position of almost complete ignorance. Still, he seems to have the appetite and energy to master the issues. He's working on creating an index of value for the arts (again, veteran watchers of cultural policy will feel a sense of deja vu), and setting off on pilgrimages to get a sense of the arts in the regions. "Frankly, it's a joy – most of the people within this world are naturally interesting characters. There are some great characters in the British army, but by and large it's a different kind of person to someone I would be sat next to at the theatre or the ballet."

What of his own hinterland? Army life, he says, left little in the way of leisure time. "But reading is something people did a lot because the reality is you might not have electricity. If you are deployed in a forward operating base, to have a book with you is a good way of trying to shut off from the world around you." What did he read in Afghanistan? "Something like Charles Dickens is a good thing because it's very descriptive … I am interested in political biographies and diaries. Alan Clark's diaries and Chris Mullin's. If something is genuinely funny, that's quite a good thing."

I'm intrigued: what Dickens did he read? "Well, I think I've probably read them all at different times. When people ask me about Afghanistan, my favourite way of describing it is through a Dickens quote: best of times, worst of times. I am not going to say I spent hours reading Dickens in Afghanistan because I didn't and that's not how it was. But I did dip in and out. I quite enjoy having a number of books on the go. My bedside cabinet has seven or eight books on it."

I wonder what he's reading at the moment, and he confesses to Mehdi Hasan and James Macintyre's recent biography of his boss, Ed Miliband. He likes Wilfred Thesiger, author of classic travel books Arabian Sands and The Marsh Arabs, although "he was quite a peculiar character … not someone you'd want to share a tent with". Somewhat wistfully, he adds: "The nature of my life is I can't go to the Hindu Kush and spend weeks or months there, or the Himalayas or the Karakoram or K2. As Basil Fawlty said, 'That particular avenue of pleasure has been closed off.' But I can access it, albeit briefly, through books."

He tells me he has come to understand the deep emotional power of images. When his wife died, he was drawn to a photograph of the Welsh mountain Cader Idris, taken by his friend Robin Goodlad. "I have probably been up that mountain 50 times," he says. "There's a great local legend that says if you spend the night on the summit, as I have several times, you either end up as a madman or a poet. It's very isolated and remote. I got hold of Robin's photo and put it in my bedroom and I found it comforting." How on earth did he cope? "You have two options. You deal with it or you don't. If you have two kids, your ability to be up on the moors wailing about it is limited. I have always been at my best when my back's been against the wall."

The traditional question to politicians beginning an arts job is what they've seen recently at the cinema: a rough-and-ready indicator of how in touch they are culturally. Jarvis doesn't even get on to the scoreboard, saying: "This position doesn't afford luxurious opportunities to stroll out to the cinema." But he does watch films on DVD: recently Hope and Glory, John Boorman's 1987 tale of a young boy growing up during the Blitz; and 1994's Muriel's Wedding. He also enjoys The X Factor.

I had previously suggested to Jarvis that he see Michael Sheen in Hamlet at the Young Vic in London. What did he think? "It's quite a long production. I arrived at a quarter to seven and didn't leave till after 11. I confess, I turned my phone on during the interval. I still find, to be honest, that it takes me 45 minutes to an hour to ease into watching something because my mind's still whirring away. But I thought Michael Sheen was amazing. By anybody's standards, it was a deeply impressive performance."

Jarvis is a confusing proposition as shadow culture minister. On the one hand, there is his self-confessed unfamiliarity with the subject. But that is offset by what is clearly a burning sense of duty, wrought from years in the army, to do a job well. The danger is that as soon as he has assimilated enough to be an effective shadow to Ed Vaizey, he will be reshuffled. Needless to say, he counters this, saying that he hopes he and his boss, shadow culture secretary Harriet Harman, will be doing their current jobs in government in three and a half years' time.

"I have genuinely become passionate about this," he says. "I see great opportunities to do great things. I'm not doing this on the back of a fag packet."