The Magnum agency, set up by photojournalists Robert Capa, David Seymour, Henri Cartier-Bresson and George Rodger in 1947, was a product of the jittery postwar era and of an existentialist philosophy attuned to the anxious mood of the times. According to Cartier-Bresson, a photograph recorded a "decisive moment", and that instant could mean, as it does for the heroes of novels by Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus, the difference between life and death.

Magnum photographers specialised in catching such moments of truth. Capa huddled with an American infantryman who was picked off by a Nazi sniper in Leipzig just before the allies declared victory, and Elliott Erwitt saw the cold war almost ignite as Nixon, touring an exhibition of American domestic appliances in Moscow, jabbed Khrushchev's bullish chest with an angry, accusing finger. More light-hearted and light-headed, Marc Riboud watched a painter with no safety harness recklessly dance on the iron girders of the Eiffel Tower like a Nietzschean superman on a tightrope above the abyss. Single gestures could show a world falling apart, or undergoing a tectonic shift: a demonstrator photographed by Bruno Barbey in Paris in 1968 hurls a rock with the elegant energy of a bowler in a cricket game, a hallooing punk photographed in 1989 by Raymond Depardon rides the suddenly permeable Berlin Wall as if it were a bucking horse at a rodeo. From a safe distance, Stuart Franklin recorded another personal and political crisis as a student carrying a shopping bag faced down the tanks advancing into Tiananmen Square and, for a single breathless minute, brought them to a halt.

Images like these conferred a Hemingwayesque bravado on the members of the Magnum coterie. They were toreadors with little Leicas, not a cape, as their only means of defence against the enemy, and they occasionally gave proof of their existential valour by being killed in action. In 1954, Capa stepped on a landmine in Indochina and Werner Bischof died in the Andes after his car plunged off a cliff. Patrick Zachmann was shot by thuggish cops in Cape Town in 1990; Cartier-Bresson commiserated, but told him to respond by using his camera as a flame-thrower. Nine years later Christopher Anderson clambered aboard a makeshift boat with a gang of Haitian refugees sailing to America. After two days it began to sink. Anderson frantically documented his own imminent death, and in a paraphrase of the Magnum creed, called the episode "the single most transformative moment of my photographic life". Fortuitously, those on the leaky homemade craft were rescued by a US coastguard cutter.

When a skirmish with death was not part of the assignment, Magnum photographs tended to be happy accidents. Inge Morath could not believe her luck when a llama inquisitively poked its head out of a car window in Times Square, and Martine Franck, preparing a photo-essay on Buddhist monks in Nepal, rejoiced when a pigeon fluttered into the room and settled on the bald pate of a blissfully unruffled holy man. Franck, Cartier-Bresson's widow, says that she is still "pursuing the unexpected" – or perhaps responding to it when it adventitiously occurs.

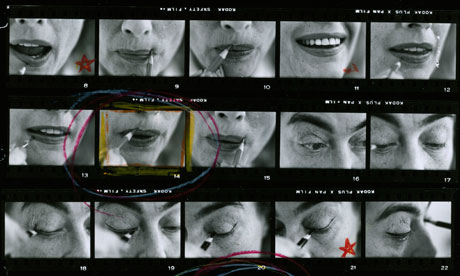

But how far was the mystique of the decisive moment a self-glorifying fiction? Photographers compulsively overshoot, and for every image that looks definitive, there are dozens that are discarded. Kristen Lubben's anthology of contact sheets – the equivalent of cinematic rushes, a memento of the days when rolls of film were printed out to be reviewed and edited – aims to illuminate the creative process but in fact demystifies it, distracting us with irrelevant alternatives like the out-takes from films that are often so otiosely added to DVDs. Cartier-Bresson thought of contact sheets as a mess of erasures, and said that when you invited friends to dinner you spared them the sight of your messy kitchen with its buckets of vegetable peel; he mostly took the wise precaution of cutting up sheets that contained no image worth enlarging.

Very occasionally, the frames before and after the decisive one help to tell a story: it's fun to discover that the disoriented llama shared its trainer's Manhattan apartment with a freakish menagerie of performers that included a kangaroo and a miniature bull, and was on its way to a gig in a television studio when Morath saw it. Otherwise I'm content not to know about images that the photographers, for good reason, chose to discard.

But Lubben's volume – a coffee-table book bulky enough to double as a coffee table – valuably documents Magnum's history, and in doing so looks beyond so-called "iconic" shots such as René Burri's Che Guevara sucking a cheroot like a stick of dynamite or Peter Marlow's Margaret Thatcher sporting a bouffant hair-do with the adamantine consistency of spun steel. There are revelations here: in the surf at Bondi, Trent Parke gulps for air, submerges, shoots at random, and comes up with astonishing images of flailing bodies that seem to fall out of the air, and in a snowy Warsaw park Mark Power photographs a dalmatian dog that like Lewis Carroll's Cheshire cat disappears into the blank vista, leaving only its spots behind.

Some of Magnum's current members doggedly pursue the humanistic mission of the agency's founders, like John Vink with his earnest agenda of "aftermath situations, threats to cultural identity, development issues, the uprooted, the voiceless" – a shopping list of liberal gripes. But Vink's colleague Martin Parr has forgotten that photographic moments ought to be decisive, and amuses himself by taking pictures of whatever banal scrap of reality flickers in front of his eye. (Once, in Dubai, he even unwittingly snapped me, along with the mob of other strangers who happened to be in the room.) Is digital photography all too facile, eliminating the editorial stage and licensing visual promiscuity? If so, these contact sheets, souvenirs of a technology that is now obsolete, are the elegy for a lost art.