In 1918, Harry Houdini made a fully-grown elephant vanish from the stage of the New York Hippodrome. He could escape from locked boxes, wriggle out of straitjackets while dangling from a crane, and once spent 91 minutes in a galvanised iron coffin submerged at the bottom of a hotel swimming pool, unruffled even when one of the men weighing down the box slipped and the whole thing shot out of the water and somersaulted through the air. Little wonder that his friend, the ardent spiritualist Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, was convinced he possessed the "divine" gift of dematerialisation, despite all Houdini's protestations to the contrary.

This stubborn refusal to doubt the evidence of his senses was entirely characteristic of Conan Doyle. The son of a Scottish alcoholic, he abandoned a career as a doctor to chance it as a writer, first unleashing the pre-eminently rational Sherlock Holmes on the world in 1887. But as he once observed: "The doll and its maker are never identical." Despite his hearty cricketer's exterior, Conan Doyle developed an interest in spiritualism that, after the death of his eldest son in the first world war, bloomed into the guiding obsession of his life. Soon, the inventor of the world's most logical detective was preaching to the nation on life after death, fairies, automatic writing, spirit photography and ectoplasm, as well as publishing books of predictions from his wife's spirit guide, Pheneas.

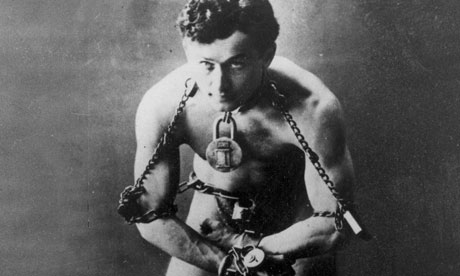

Houdini, on the other hand, was a supreme sceptic, pre-empting the likes of Ben Goldacre and James Randi with his medium-busting activities. Born Erik Weisz in Budapest in 1874, he cut his teeth in the touring medicine shows of the early 20th century, performing his illusions alongside hootchy-kootchy girls, contortionists and sundry sideshow freaks. Several of his co-workers later re-emerged on the lucrative seance scene, converting their skills for stagecraft into an ability to read minds or conjure the lost voices of the dead. From the beginning, this unlikely friendship was established around a mutual interest in the existence of an afterlife. Both men were besotted with their mothers, and after the death of Mrs Weisz, Houdini experimented abortively with seances (it may, though Sandford doesn't say as much, have been this personal knowledge of the bereaved's vulnerability that drove his later exposés). Conan Doyle hoped his new companion would explore what seemed astounding psychic gifts. Unfortunately, Houdini's training and nature made him unsympathetic to the question of supernatural phenomena. "Applesauce" and "hogwash", he commented in private of his friend's beliefs.

The relationship foundered when he began to debunk mediums publicly, both on stage and under the auspices of Scientific American (the title of a later work, Miracle Mongers and Their Methods: A Complete Exposé of the Modus Operandi of Fire Eaters, Heat Resisters, Venomous Reptile Defiers, Sword Swallowers, Human Ostriches, Strong Men, Etc, gives a sense of the lively nature of these proceedings). Most devastating for Conan Doyle was his investigation of Margery Crandon, an attractive blonde Boston Brahmin who often performed in the nude and apparently secreted ectoplasm in her vagina. Conan Doyle took this exposé as a personal betrayal, and the friendship devolved into a feud carried out mainly via newspapers.

As these lurid details suggest, this is a magnificently rich story, albeit unsatisfactorily told. The first half of the book is dedicated to inching Conan Doyle through his early years, though occasional side glances at Houdini suggest his childhood was considerably more colourful. The men don't meet until chapter four, while repeated fast-forwards make for a repetition of detail.

More troubling, and stranger, is Sandford's partisanship on the part of Conan Doyle, whose sweet and sportsmanlike nature apparently trumps his insistence on consoling fantasy over the uncomfortable realities of scientific proof. There are frequent references to Houdini's diminutive stature, crumpled clothes and inability to spell (describing himself as Conan Doyle's intellectual "pier" is a cracker, no doubt), all of which would be fine if they were accompanied by the same note of respect that Conan Doyle automatically commands.

It seems self-evident that Houdini's scepticism was admirable, even if sometimes motivated by a concurrent desire for publicity, and ending the book by congratulating Conan Doyle on his message of hope is palpably absurd. No matter. The self-made illusionist who couldn't tolerate a lie remains a bewitchingly impressive figure, however badly dressed he is.

Olivia Laing's To the River is published by Canongate