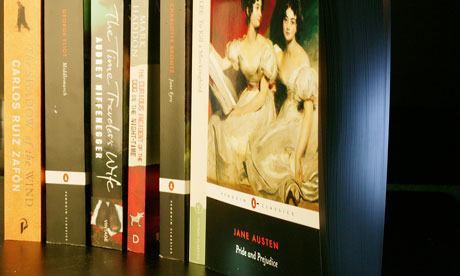

Michael Gove is apparently shocked that British students aren't reading enough Victorian novels. To anyone teaching literature at university, as I do, this comes as something of a belated revelation. And there is much in what Gove says with which I entirely concur. His finding that very few students in the English literature exams last year wrote about Pride and Prejudice, Wuthering Heights or Far From the Madding Crowd, while more than 90% of answers were based on the same three novels – Of Mice and Men, Lord of the Flies and To Kill A Mockingbird – is entirely consistent with my experience.

On the evidence of classroom discussion, the vast majority of my incoming students seem to have only read those three books. In fact, affirmative teaching – teaching to exams – often means these students also know the same five things about those three books. It doesn't make for a wide-ranging conversation.

Gove has demanded that we create a culture of reading, and wants to challenge the accepted wisdom that "the idea of a canon is outmoded" or "it's all on the internet anyway". He says, rightly, that such a culture is "anti-knowledge, anti-aspiration and antithetical to human flourishing", and calls for a culture "in which the more you read, the more you are celebrated".

Well, count me in: that would certainly be a welcome change. But the schools are hardly to blame for the fact that we don't live in a culture that "celebrates" people the more they read. I read a great many books, and I'm fairly certain I'm not celebrated for it. I'm quite certain I'm not well rewarded for it, at least not financially – and that, if you look at what Gove's colleagues are doing, appears to be the only kind of reward the government recognises.

The schools are working, like all of us, to stay afloat in a hostile environment that tells them they're doing their jobs badly, while cutting funding and telling them to do better with fewer staff. Meanwhile, the government also insists that teaching become ever more utilitarian, vocational training for future jobs. Unless the entire nation is going to teach Victorian novels for a living to all the students who will now be clamouring to read them, Gove is going to have a hard time squaring this circle.

Instead of pointing fingers at schools, Gove might look closer to home: across the corridors of Whitehall, to a universities minister who looks set to implement the Browne report's recommendation to cut 100% of funding for the teaching of the humanities at universities. In fact, the word "humanities" never appears in the Browne report's 67 pages on the future of universities in this country, which tells us all we need to know. Will this really be a culture that celebrates reading?

Gove might also expand his own idea of the literary canon, which does not begin and end with 19th-century Britain. That may have been a jolly time to be British (at least in our historical fantasies: the novels he names tell a different tale), but as an American I would remind him that we contributed some important books to world culture before 1940, too. I'd also like to think that literature students were familiar enough with Shakespeare's plays to be able to write comfortably about them in exams, for example.

But Gove is quite right that rethinking the literary canon should never have meant throwing it out. I'm all for admitting more books into the conversation, but contemporary novels are neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for being a true student of literature. But the question isn't really when books were written: there is much to learn from contemporary literature, too. The issue is with the range and breadth of our reading across history and culture. Far from narrowing the conversation, wide reading in (and out of) the canon expands it.

What great literature teaches is profoundly social: it teaches us to see the world from other peoples' perspectives, in other times and places. Whether we are following the struggles of an orphan girl in Jane Eyre, floating down a riverboat with an escaped slave in Huckleberry Finn or standing on a cliff being pelted by a storm in King Lear, what we are not doing is simply reconfirming our own points of view.

Confining ourselves to books that explicitly correspond to our own experiences is as solipsistic as flicking through a photo album looking only for pictures of oneself. I agree with Gove that we would be immensely better off if we lived in a culture that celebrated reading, instead of only the arid chasing of wealth. I just hope he can convince his ministerial colleagues to put our money where his mouth is.